The four centuries between the Old Testament (Tanakh) and the Gospels are sometimes called the “Silent Years”. This time period is also known as the intertestamental or deuterocanonical period. Yet there are historical sources and archaeological evidence that can take away the veil of silence. The Works of Josephus, the Books of Maccabees and Ecclesiasticus, also called the Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach, and others, contain important information about this enigmatic time. Beginning with the conquests of Alexander the Great, the new culture of Hellenism changed the way people were thinking and acting. These changes can be detected in archaeology, ancient architecture, politics, culture and religion. During this time, three empires, Persia, Greece and Rome successively ruled the then-known world. In this brief outline, we hope to cast some light on this fascinating period in the history of the Jewish people, and especially on Jerusalem and the Temple Mount.

After the death of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, his empire was split among four generals, known as the diadochi. Alexander and his successors imposed the Hellenistic culture on their new subjects. The Hellenistic period in Judea lasted from 332-152 BCE, and that was followed by the Hasmonean kingdom which terminated when Herod the Great became king in 37 BCE. During this period, Judea was first under Ptolemaic rule from 301-200 BCE. The Ptolemies were benevolent toward the Jews. Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who ruled from 285-246 BCE, commissioned a translation of the Hebrew Bible in c. 250 BCE. Seventy-two scholars from Jerusalem translated the Torah, the five books of Moses, into Greek.

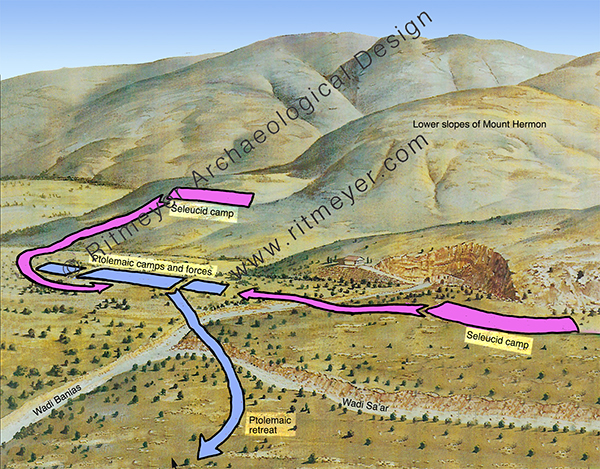

During the 3rd century BCE, many battles took place between the Ptolemies in the south and the Seleucids in the north. In 200 BCE, a final battle between the two forces took place in Panion (modern Banias) which was lost by the Ptolemies. The Seleucids then controlled the Holy Land.

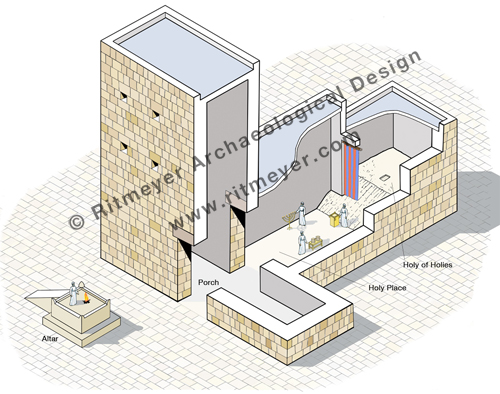

The Temple that was built by Jeshua and Zerubbabel three centuries earlier undoubtedly needed structural maintenance and repairs.

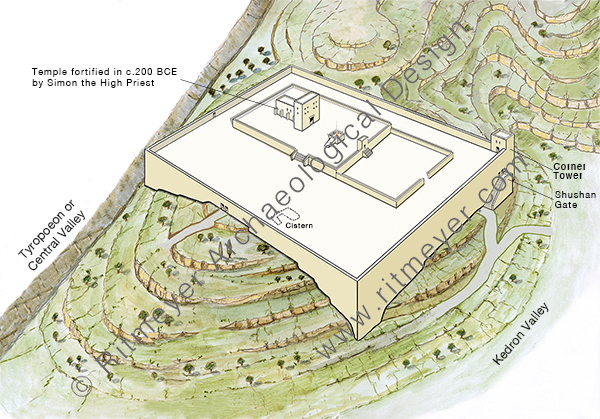

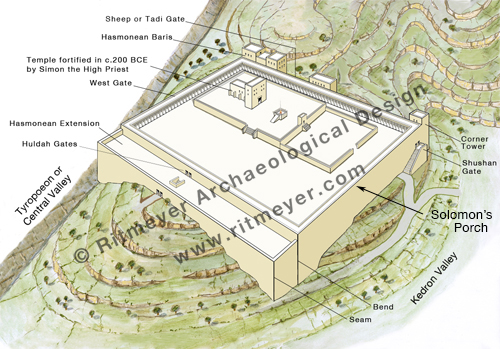

In 200 BCE, restoration work was indeed carried out on the Temple Mount. In the deuterocanonical book of the Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach, also called Ecclesiasticus, the work is described as follows:

“It was the High Priest Simon son of Onias who repaired the Temple during his lifetime and in his day fortified the sanctuary. He laid the foundations of the double height, the high buttresses of the Temple precincts. In his day the water cistern was excavated, a reservoir as huge as the sea.” (50.1-3).

It is clear from this text that the bulk of these works were concerned with the repair and strengthening of existing structures, as no archaeological remains can be demonstrated as belonging to this enterprise. The cistern that was excavated was probably initially quarried to supply stones for the repair work, and was afterwards used as a water cistern.

Whereas the Ptolemies were benevolent rulers, the Seleucids were the very opposite. The most infamous of the Seleucid rulers, Antiochus Epiphanes went to Jerusalem in 169 BCE, where he plundered the Temple, sacrificed a pig on the Temple altar, and and took all the Temple furniture and treasures away to Antioch. He was determined to Hellenize all the Jews in Judea, forbidding worship on the Temple Mount and the practice of rituals, such as sacrifice and circumcision and compelled them, on penalty of death, to sacrifice to pagan gods. This sparked off the revolt led initially by Mattathias, and then by his five sons, Eleazar, Simon, Judah, John and Jonathan, known as the Maccabees, and which lasted from 167 to 160 BCE.

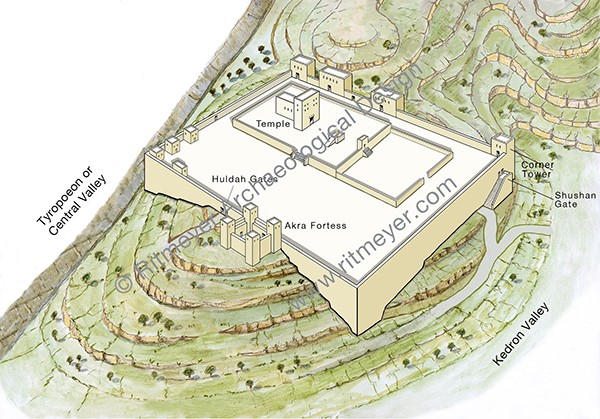

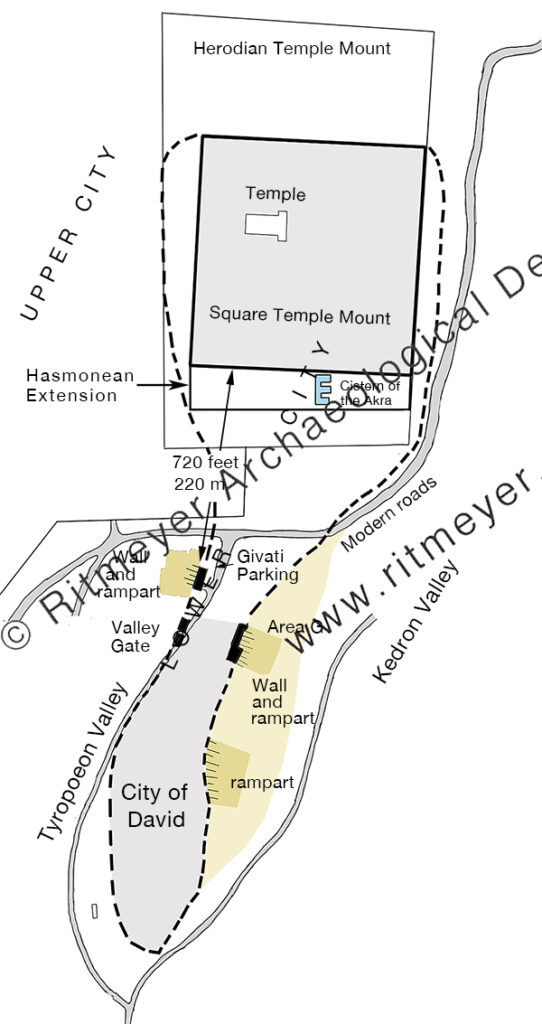

In 168 B.C. Antiochus IV Epiphanes built the Akra, a fortress for his Macedonian garrison, from which the Jewish population could be controlled. Hellenized Jews also joined this garrison. Josephus records that it commanded or overlooked the Temple. Josephus writes in Antiquities 12.252 that Antiochus …

built the Akra in the Lower City; for it was high enough to overlook the Temple, and it was for this reason that he fortified it with high walls and towers, and stationed a Macedonian garrison therein. Nonetheless there remained in the Akra those of the (Jewish) people who were impious and of bad character, and at their hands the citizens were destined to suffer many terrible things.

This description agrees with that given by the author of the Books of Maccabees, who, when referring to the event mentioned above, puts the Akra in the Lower City, which he calls the City of David:

They fortified the City of David with a great and strong wall, with strong towers, and it became unto them an Akra. There they installed an army of sinful men, renegades, who fortified themselves inside it, storing arms and provisions, and depositing there the loot they had collected from Jerusalem; they were to prove a great trouble. It became an ambush for the sanctuary, an evil adversary for Israel at all times. (1 Maccabees 1.33–36)

Archaeological remains of the fortifications have been found:

When in 168 BCE, an imperial emissary came to Modiin demanding that the people sacrificed on a pagan altar, Mattathias the priest refused to obey. When one of his countrymen came forward to sacrifice, Mattathias killed him and the emissary. This was the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt (1 Maccabees 2:23-25). Mattathias, his sons and many villagers left Modiin immediately and set up camp in the Gophna Hills, from where they fought many battles against the Seleucid army.

In 164 BCE, Judas, the eldest son of Mattathias, defeated the Seleucid forces at the battle of Beth-zur, and when he and his men went up to Jerusalem to purify and dedicate the sanctuary, they found the Temple in a shocking state of neglect and its buildings in ruins. After they had purified the Temple and a new altar was built, there was great rejoicing. It was then decided to make a law that the keeping of this Feast of Dedication (Hanukkah) would be kept every year for eight days (1 Maccabees 4:36-61; 2 Maccabees 10:1-8). This Dedication of the Temple is still celebrated today by the Jewish people during the feast of Hanukkah, and, as three New Testament references (John 10:23, Acts 3:11, 5:12) show, was also observed by Jesus and his disciples.

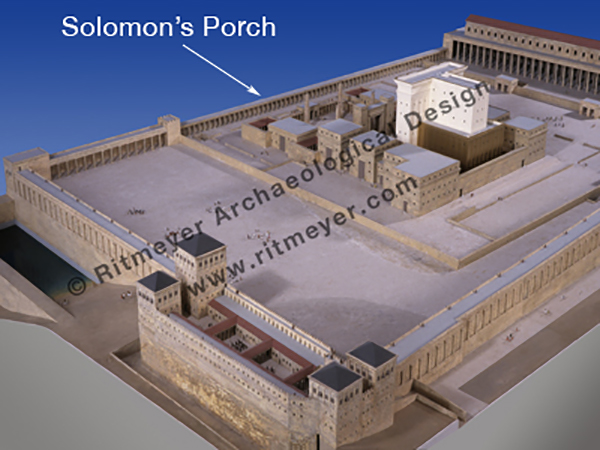

In 142 BCE, Simon the Maccabee demolished the hated Akra, the fortress that the Seleucids had built to the south of the Temple Mount. He then leveled the mountain on which it was built, incorporating the whole area into the Temple Mount complex. The bloodline of the Maccabees evolved into the Hasmonean dynasty that established an independent Jewish state lasting till 37 BCE, when Herod the Great became king of Judea.

So, when Jesus walked here and taught the people, it would have reminded them of a unique point unparalleled in their history, when they celebrated God’s intervention in the restoration of their place of worship. And when the name of Solomon’s Porch was used for the eastern stoa, it represented a powerful connection with the dedication of both Solomon’s and the Hasmonean Temple, allowing the silent years to speak.