I have seen many models of the Temple Mount and designed some myself, but I have never seen a model made of Lego bricks. Joshua Hanlon made his model of the Second Temple of Jerusalem which is on display at Brickworld Fort Wayne 2016:

Ritmeyer Archaeological Design

…for the latest research, analysis and products on Biblical Archaeology

Todd Bolen of Bibleplaces.com has finished a new DVD photo project to illustrate the Life of Christ. Many Bible teachers and scholars alike would benefit from this collection as it uses a variety of photographs, both modern and historic, to illustrate virtually every verse in the Gospels.

The Israel HaYom Newsletter announced today that new 10 ancient storage jars have been found in a new excavation in Shiloh:

Excavation at ancient Shiloh seeks to locate site of Jewish tabernacle that dates to the time the Jewish people first arrived in the land of Israel • “This is a very exciting find,” says Archaeology Coordinator in the Civil Administration Hanania Hizmi.

During the months of May/June 2017, excavations were carried out at Tel Shiloh[1]. At the conclusion of the dig, conservation work[2] needed to be carried out on some walls that were in danger of deterioration or collapse.

One section of the Middle Bronze Age city wall, W17 in Square AC-30, was selected for conservation. This wall was built of large ashlars, but in between these large stones were patches of small stones that needed to be consolidated (Fig. 1).

We are pleased to say that we are back online after a week of outage. Will post soon again.

Carta, the well-known Jerusalem publishers, offers an introductory price on our latest, and eighth, Carta book, valid until June 30, 2017 (make sure to put in the discount code: “25-off”):

This title is part of the “Understanding” series of Carta: Continue reading “Understanding The Holy Temple Jesus Knew”

Two new apps have been developed to help visitors visualize ancient Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount. The BYU has developed a free app, which can be downloaded here.

The Virtual New Testament app is one of the most accurate digital recreations of first-century Jerusalem. It’s purpose is to enhance scripture study by allowing you to experience the city, engage with the environment, and immerse yourself in the world of Jesus’ mortal ministry.

This app works for both Mac and Windows desktops and can be downloaded for mobile devices at the Apple App Store or at Google Play.

The Jewish News Online reported on another app that was developed by Lithodomos VR. This app only costs a couple of dollars and is worth getting if you have a Virtual Reality headset. An introduction can also be viewed on YouTube.

Young and old alike now have the chance to wander the streets of ancient Jerusalem, after archaeologists recreated the city at the time of King Herod in a virtual reality headset.

Half a million pounds of investor funding helped created the Android app, called Lithodomos VR, based on the archaeology of Temple Mount in 20BC, before it was destroyed some 90 years later.

The app (at £1.59 or S2.00) and headset let the user experience market streets, the Western Wall, the temple precinct, and the Jewish and Roman period districts, with buildings virtually reconstructed based on the latest archaeological evidence.

On Sunday, the 10th of April, 2017, the Jewish people begin celebrating Pesach – Jewish Passover. That is one week earlier than Easter. However, in this blog post we would like to remember the time that Jesus as a twelve-year-old visited the Temple during Passover for the first time in his life.

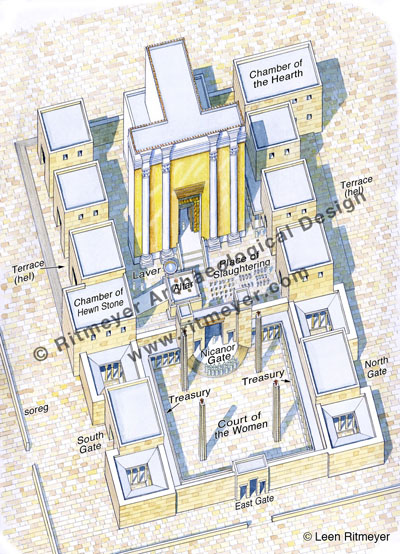

The Temple in the time of Christ was a magnificent building. From the Temple Court (azarah), 12 steps led up to the Porch that was as high as the Temple itself. In front of the entrance to the Sanctuary, a Golden Vine was attached to four columns.

The central feature of this complex, the Holy of Holies, was located deep inside, at the west end of the Sanctuary. No one could enter this place of utmost sanctity but the High Priest once a year on the Day of Atonement. A veil separated the Holy of Holies from a place of lesser sanctity, the Holy Place.

The Temple Court lay in front of the Temple and it contained the Altar, the Laver and the Place of Slaughtering (or Shambles). This was the closest court to the Temple and out of bounds to anyone like Jesus who was not a priest.

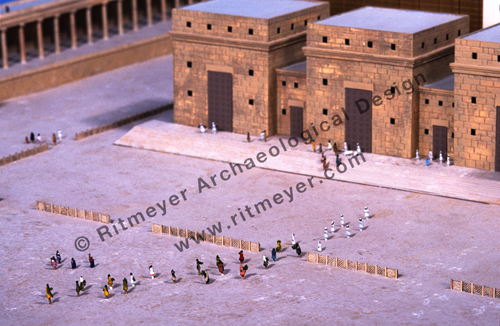

This Temple Court was separated by the Nicanor Gate from the Court of Women, which lay to the east of the Temple. Buildings, called gates, surrounded this complex. In front of the gates was a terrace (ḥel – pronounced chel with the “ch” sounding guttural as in the Scottish “loch”) of 10 cubits wide, which was reached by a flight of steps of half a cubit high and deep. This terrace bounded the wall of the gate buildings on their southern, western and northern sides.

It is on this ḥel that we get our first glimpse of Jesus after the birth narratives in the Gospels. Scripture is silent about his youth although it is clear from the observations of nature and Biblical history later attributed to him by the Gospel writers that he absorbed every spiritual and historical lesson that was provided by his upbringing in the countryside around Nazareth.

Now he was twelve years of age and his first words are recorded for us (Luke 2. 41-52). Under the law, attendance at the feasts in Jerusalem was obligatory for boys from the age of thirteen, a birthday that was a milestone in the life of a Jewish boy, when they became a Son of the Commandment or Bar Mitzvah. In practice, this legal age was pushed forward by one or two years so that Jesus, after he had passed his twelfth year, came up to Jerusalem for the Passover with his family. Jesus’ first view of the Temple must have filled him with a great sense of the purpose he had been developing during the quiet years in Nazareth. Attendance at the Temple was obligatory only for the first two days of Passover, after which many of the pilgrims would have returned home again. It would appear that Joseph and Mary and their “company” did indeed start to return home and had travelled for a day. When they finally realized that Jesus was missing, it took them three days to find him and when they did, he was “in the temple, sitting in the midst of the doctors, both hearing them and asking them questions.” The ḥel is the only place in the Temple he could have been.

We learn this from a tractate of the Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 88b, which tells us:

“It has been taught; R. Jose said; Originally there were not many disputes in Israel, but one Beth din of seventy-one members sat in the Hall of Hewn Stones, and two courts of twenty-three sat, one at the entrance of the Temple Mount and one at the door of the [Temple] Court, and other courts of twenty-three sat in all Jewish cities.” “The Great Sanhedrin] sat from the morning tamid (daily sacrifice) until the evening tamid [in the Hall of Hewn Stones]; on Sabbaths and festivals they sat within the ḥel.”

So, Passover would have been one such festival when members of the Temple Sanhedrin would come out to teach in this area. Ordinary people, who normally had no access to the classrooms where young priests were taught, could come and question them. Jesus must have eagerly made use of this opportunity and never would they have had such a sharp student as him. During this visit to the Temple, he would have seen the preparations for sacrificing the Passover lambs and realized, perhaps for the first time in his young life, that the entire ritual pointed forward to his own sacrifice. He would have been so absorbed by all these experiences that he would not have wanted to leave. He forgot about his natural family, for here he was at home – in his Father’s house.

The Israel Hayom newspaper reported yesterday that a capital of the 2nd Temple era has been found by the Temple Mount Sifting Project (TMSP).

Photo credit: Vladimir Naychin

The capital of a carefully-adorned column that stood on the Temple Mount in the time of the Second Temple has been discovered through the Temple Mount Sifting Project.

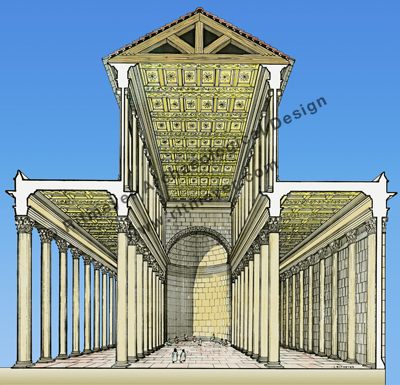

The capital, whose size indicates that the column had a circumference of 75 centimeters (30 inches) at its top, is a section of one column that formed part of the double colonnade that surrounded the Temple Mount plaza.

Dr. Gabriel Barkay, the director of the Temple Mount Sifting Project, said that “this is a capital in the Doric style, one of the characteristics of the art in the time of the Hasmonean dynasty. This appears to be the capital of a column formed part of the eastern colonnade of the Temple Mount, which Josephus and even the New Testament called ‘Solomon’s Porch.’ A column like this is impressive testimony of the immensity of the structures on the Temple Mount in the Second Temple era, and fits in well with Josephus’ narrative, which describes what he saw with his own eyes.”

Barkay explained that a 25-cubit column would have stood 12.5 meters (41 feet) high.

It is of course wonderful news that a capital of a column that most likely stood on the Temple Mount was found. I would agree with Barkay that the capital could have belonged to one of the columns that formed the eastern Hasmonean (pre-Herodian) colonnade. This colonnade was indeed known as Solomon’s Porch, where Jesus walked during Hanukkah (John 10.23). It was also the place where Peter and John healed the blind man (Acts 3.11) and where the apostles did many signs (Acts 5.12).

One must, however, be careful with dimensions. In the article it says that the circumference of the Doric column that supported the capital was 75 cm. That is probably a mistake. According to simple mathematics, a column with a circumference of 75 cm (30 inches) has a diameter of less than 24cm (9 inches). In ancient architecture, Doric columns had a 1:8 ratio between diameter and height. According to that rule, this column could not have been higher than 2m (6 feet, 6 inches), which would not have been exactly monumental. Barkay therefore probably meant that the column had a diameter of 75cm. In that case, the column would have been about 6m (20 feet, 11.4 cubits) high. Barkay estimated that a 25-cubit column would have stood 12.5 meters (41 feet) high, but this one would have much smaller, about half the size.

An additional problem is the use of units of measurement by Josephus. In War, he uses cubits and in Antiquities (Roman) feet. As a rule, his measurements in feet are more accurate than those in cubits, which are often exaggerated.

Josephus writes in War 5.190-192, that the columns of the Herodian porticoes were 25 cubits, which according to the Royal Cubit of 52.5 cm (20.67 inches), would be 13.12m, (43 feet) high, but in Ant. 15.413 he says that the columns of the porticoes were 27 feet high (8.23m, 15.67 cubits). Let us first look at the 25 cubits high columns and then at those of 27 feet high.

According to the Doric ratio of diameter and height, the diameter of a 25 cubit high Doric column must have been 1.64m (5 feet, 5 inches). Archaeological remains of parts of such thick columns have been found in secondary use in the Temple Mount excavations in front of a gate of an Umayyad palace. A complete column with a diameter of 1.46m (4 feet, 9 inches) has been preserved in the Double Gate underground passageway. Josephus mentions in Ant. 15.415 that the height of the Corinthian columns (which have a ratio of 1:10) of the Royal Stoa were 50 feet (15.24m or 29 cubits) high, probably including the capitals. This measurement is somewhat similar to the 25 cubits high columns of War 5.190-192 and must therefore relate to the columns of the Royal Stoa and not to those of the porticoes. Columns of that height could only have belonged to the Royal Stoa.

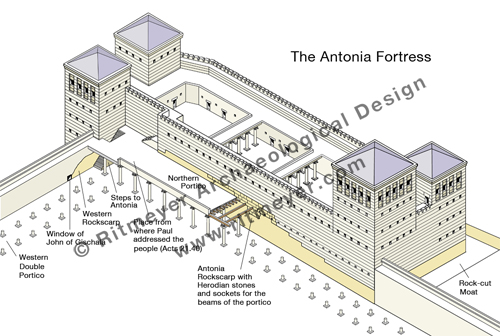

Going back to Ant. 15.413, where Josephus writes that the columns of the porticoes were 27 feet (8.23m) high, we found that this measurement is indeed correct for the Herodian porticoes. The preserved sockets of the northern portico can still be seen in the south wall of the Antonia Fortress (see drawing). They are located 8.84m (29 feet) above ground level. As the beams that were laid on top of the capitals were fixed in these sockets, Josephus’ measurement of 27 feet appears to be accurate.

The reconstructed height of the newly found Hasmonean column of 6m (20 feet) is a little lower than those of the Herodian columns. The older Hasmonean portico, also known as “Solomon’s Porch”, was apparently not as high as the Herodian colonnades, as indicated in this reconstruction model.

Last year, Carta of Jerusalem asked us to write two new books for their “Understanding …” series. The first one, Understanding The Holy Temple of the Old Testament, From the Tabernacle to Solomon’s Temple and Beyond was published last year and the other one Understanding The Temple Jesus Knew will hopefully be published this year.

In this series, Carta has published titles such as Understanding Biblical Archaeology, Understanding the New Testament, Understanding the Alphabet of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Understanding the Boat From the Time of Jesus and many more.

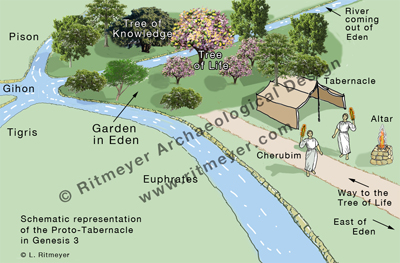

As we have written extensively on the Temple Mount it was difficult to give a new slant to this book without repeating ourselves too much. We therefore decided to go back in history and see where the idea of holiness and a sanctuary came from. We found it in the Book of Genesis.

In the early chapters of Genesis we read that God created a garden in Eden and placed Adam and Eve in it to look after it. God Himself walked in this garden (Gen. 3:8) and therefore it represented the dwelling place of God, comparable to the Holy of Holies of the later Tabernacle and Jerusalem Temples. God spoke in the Garden of Eden and also in the Holy of Holies that is sometimes called debir (oracle, derived from dabar, to speak). A similar expression of God walking in a sacred space is used of the Tabernacle (Lev. 26:11,12):

And I will set my tabernacle among you: and my soul shall not abhor you. And I will walk among you, and will be your God, and ye shall be my people.

One of the earliest extra-biblical references to the Garden of Eden being a representation of the Temple comes from the apocryphal Book of Jubilees 8:19:

“[Noah] knew that the Garden of Eden is the holy of holies, and the dwelling place of the Lord.”

Adam was given a charge to dress (abad —work) and keep (shamar —watch) the garden:

And the LORD God took the man, and put him into the Garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it. (Gen. 2:15)

The Hebrew verbs ‘to dress’ and ‘to keep’ are also used to describe the work of the priests in the Tabernacle (Num. 3:6,7):

Bring the tribe of Levi near, and present them before Aaron the priest, that they may minister unto him. And they shall keep his charge (derived from shamar), and the charge of the whole congregation before the tabernacle of the congregation, to do the service (derived from abad) of the tabernacle.

It could be suggested therefore that Adam was given a priestly duty to look after this garden-sanctuary.

After Adam and Eve were exiled from the Garden of Eden, cherubim with a flaming sword that turned in all directions were placed to the east of the garden to prevent their return. In Hebrew, the word “placed” (yasken), in Genesis 3:24, is closely related to the word for Tabernacle, which is mishkan in Hebrew. The original language appears to indicate that the cherubim were made to dwell in a tent-sanctuary or tabernacle that was erected to the east of the Garden of Eden. Although little else is known about this sanctuary, the text would seem to be describing a proto-Tabernacle or Genesis Sanctuary, which would serve as a model for future meeting places between God and man.

East-facing Sanctuary

The location of the sanctuary at the east side of the garden can be compared to that of the Holy Place of the later sanctuaries of Israel. The forbidden Paradise lay therefore to the west of the guarded entrance to the Garden of Eden. A road may have run from the east to an entry point or gate in a boundary that surrounded the Garden of Eden. Here the principles of worship would have been established, creating a pattern for subsequent places of worship. Anyone wanting to visit this dwelling place would have had to approach it from the east and face west. This direction of approaching a holy place from the east has been preserved in the Tabernacle and the Temple constructions, the entrances of which all faced east, while the Holy of Holies is in the west.

The Altar

The principle of approaching God by sacrifice would also have been established in this place. The sword of the cherubim may have been used, not only to preserve the way to the Tree of Life by keeping humans out, but also for killing sacrifices and the flame for igniting the wood. It would be reasonable to suggest that the offerings that Cain and Abel brought to God were presented to these cherubim. Abel may have placed his offering on an altar. It was in this place that the cherubim, as divine representatives, would have taught Cain and Abel which sacrifices were acceptable and which ones were not. In the New Testament Book of Hebrews 11:4, we are told that God testified of Abel’s gift. Was this testifying done by the fire of the cherubim consuming Abel’s sacrifice? A similar event happened with the sacrifices brought by Gideon (Judges 6.21) and Elijah (1 Kings 18.38).

Thinking about this proto-Sanctuary in Genesis, we can see that the principles of holiness were laid out right in the beginning of the Hebrew Bible. There are many other parallels with the later Sanctuaries of Israel that are mentioned in this book. It appears, however, reasonable to suggest that this bi-partite division of a Holy of Holies and a Holy Place may have become a blueprint for later Israelite and non-Israelite sanctuaries alike.

For further reading on this topic, see:

Parry, D.W. (ed.) (1994). Temples of the Ancient World: Ritual and Symbolism (Salt Lake City).

Beale, G.K., (2004). The Temple and the Church’s Mission, a biblical theology of the dwelling place of God (Leicester).

Hamblin, W.J., (2007). Solomon’s Temple: Myth and History (London).

Beale, G.K., (2011). A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New (Grand Rapids).

Price, R. (2012). Rose Guide to the Temple (Torrance).