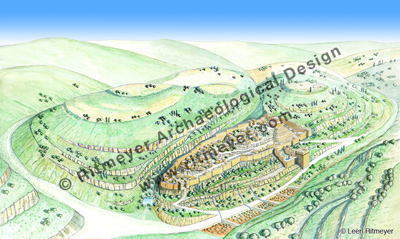

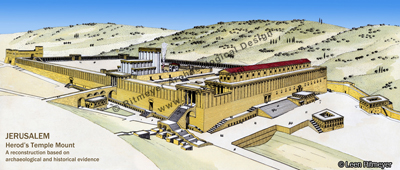

Nadav Shagrai wrote a lengthy article, called A Heart of Stone, in Israel Hayom about the amazing feat of tunneling deep underground along the foundations of the Western Wall by Eli Shukron and his team. This uncovering has undoubtedly increased our understanding of how this mighty wall, and indeed all other walls too, were constructed. It was reported earlier that some coins dating from about 17-18 CE had been found in the fill of a mikveh below the Western Wall. This find was used to suggest that not Herod the Great, but one or more of his sons completed the project.

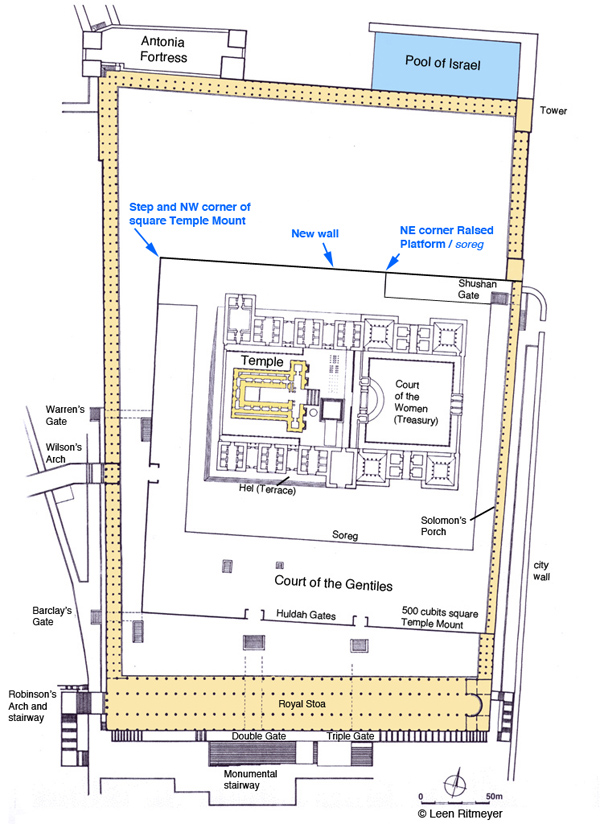

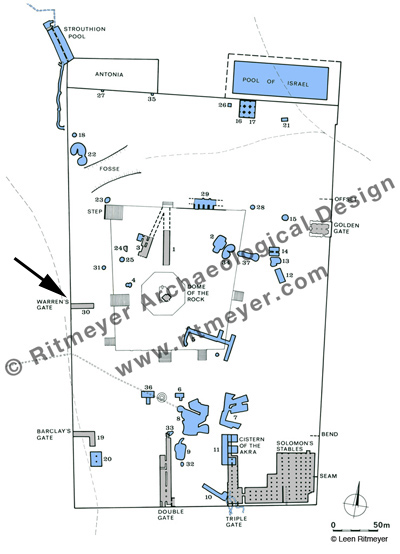

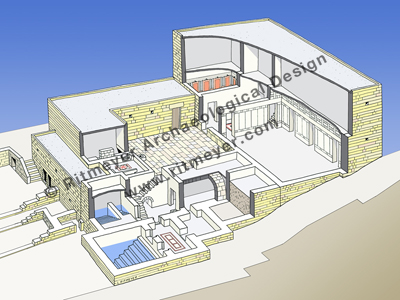

This stretch of foundation stones of the Western Wall is located right next to the main drain that runs the full length of the Herodian street that began at the Damascus Gate and ended at the southern gate near the Siloam Pool. One doesn’t need much imagination to understand that maintenance work would have frequently been carried out in and near the drain during the long period that it was in use. The filling in of the above mentioned mikveh, that was located in between the drain and the foundation of the Western Wall, could have been carried out during such work.

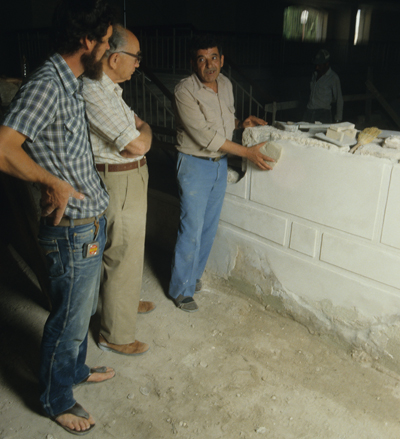

It is now also reported that one of the Herodian foundation stones had no margins, but a smooth finish. This what Eli has to say:

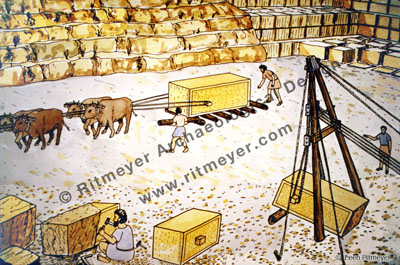

“This stone came from the Temple Mount, from the surplus stones that were used in the construction of the Temple itself. Those stones were high-quality, chiseled and smooth, like this unusual one, which was discovered among the Western Wall’s foundations. This stone was intended for the Second Temple, and stones like it were used to build the Temple — but it was left unused. The builders of the Western Wall brought it down here because it was no longer needed up above — and this is how the other stones of the Temple looked,” he says, adding, “Anyone who passes a hand gently over this stone feels a slightly wavy texture, just like the Talmud describes.”

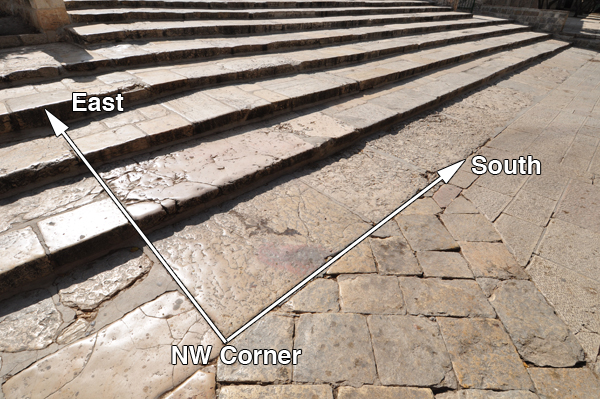

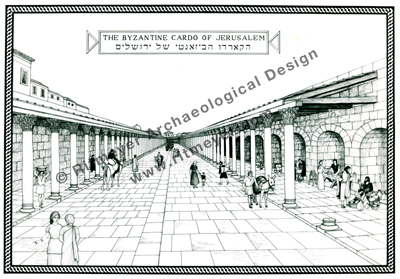

It is true that all the external faces of the Herodian stones have margins on all four sides, apart from this unique stone. The suggestion that this particular stone could have come from the Temple itself would have been a possibility if only the stones that were used to build the Temple had a smooth finish. That, however, is not the case. In studying Herodian architecture, one needs to differentiate between external and internal finishes of the stones. The internal parts of the stones that make up the retaining walls were never seen and therefore were roughly squared on the inside. The stones of the Western Wall above the level of the Temple Mount could be seen from inside the porticoes that were built all around. The interior finish of these stones was smooth. Several of these stones were found in the Temple Mount Excavations. One such stone was later reused in a Byzantine building. That stone was a pilaster stone, part of the outer wall of the porticoes that ran above the Temple Mount retaining walls. These stones had an external finish with margins, like the ones we see today, and a smooth internal finish. From the inside therefore, the portico wall looked smooth. It is quite possible, and indeed more likely, that the newly discovered smooth stone came from the porticoes and not necessarily from the Temple itself.

It is necessary to exercise caution before suggesting that this smooth stone must have come from the Temple. Although it is exciting to find the first in situ stone without margins, one needs to be careful not to draw unwarranted conclusions.

HT: Joe Lauer