| By Avigayil KadeshAs countries go, Israel is quite tiny. But as archeological sites go, it’s vast.Archeologists in search of biblical evidence have been digging up ancient treasures here since the mid-19th century,In December 2011 alone, a rare 2,000-year-old clay seal found near Jerusalem’s Western Wall was one of the few Second Temple artifacts ever unearthed; and the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) found the remains of a Byzantine bathhouse when a new water supply system in the Judean coastal hills was under construction. but shovels really started flying after Israel achieved statehood in 1948.Fascinating discoveries often make the news Also during December, researchers from Tel Aviv University published a paper on their newsworthy find from the previous year: Modern human teeth in a cave near Tel Aviv that predate by 200,000 years the African Homo sapiens. The discovery has put into place a new piece of the puzzle of human evolution. The IAA had a field day during the building of Jerusalem’s recently completed light rail. Among the discoveries were part of a Jewish village dating from around 135 CE (65 years after the Romans destroyed the Second Temple and exiled many Jews), 264 identical gold coins of the last Byzantine emperor who ruled in Jerusalem; a Roman Legion camp from the second century; a 12th-century village; and Byzantine monasteries. And in 2009, Israeli archaeologists in Migdal (near Tiberius) found the most ancient depiction of the menorah, a carving dating from the Second Temple period 2,000 years ago. Unearthing and preserving history Jon Seligman, IAA’s head of excavations and surveys, can’t help but laugh when asked to name the most notable finds over the last 64 years. “The archeology in this country has been revolutionized over the 60-plus years of the state,” he says. A complete listing of sites numbers 70: Most major archeological sites were preserved as national parks after excavations were complete. Some of these include • Masada, Herod the Great’s ancient fortress overlooking the Dead Sea (now one of Israel’s most popular tourist sites because of its dramatic role in the story of Jewish resistance against the Roman Empire; • Megiddo, a key ancient and modern crossroads that was already a fortified city with huge walls by the third millennium BCE; • Beit Guvrin-Maresha, with its thousands of years’ worth of quarries, burial caves, storerooms, industrial facilities, hideouts and dovecotes; • Ashkelon, the oldest and largest seaport known in Israel, and a thriving commercial center during the Roman period; and of course • the City of David, the nucleus of ancient Jerusalem, as well as all the Western Wall and Southern Wall areas surrounding the Temple Mount. “Each is important in its own way,” Seligman says. The IAA supervises about 300 annual excavations, accounting for about 95 percent of all the archeological digs in Israel. The digs usually take place at mounds composed of the remains of ancient settlements (tel in Hebrew). “We have 30 excavations every day,” says Seligman. Israel is so rich in archeology that even at this pace, he adds, “We can carry on for many more years.” The IAA also provides instructors for a five-month English-language program in archeology and historic preservation through the International Conservation Centre in Old Acre (Acco). In addition, Israel’s universities partner with overseas universities on summer digs open to volunteers. The digging, discovery and analyzing is part of a carefully considered process, Seligman stresses. “We have to look not only at what we excavate but also at what we don’t. We do the minimal amount necessary, since excavation is a destructive process and we have to think about what we must leave for future generations,” he explains. “In general, we try to keep material at the site in its context, and only consider bringing things to a museum when there is no alternative. A mosaic, for example, is meant to be on a floor, not hanging on a wall.” Not every excavation site is preserved for public viewing. “Maintenance is expensive, so we can’t afford to make each into a presentation site,” Seligman says. Those that aren’t developed into national parks are covered over after the archeologists have finished their investigations. Best finds Seligman and Aren Maeir, a noted archeologist from Bar-Ilan University, identified some of the most notable archeological digs in Israel over the past 25 years, listed in no particular order: • Tel Hatzor

Hatzor was a training ground for scribes.

Archeology teams have spent 22 summers digging through 22 layers of civilization at this UNESCO World Heritage site near the Lebanese border, one of the largest archaeological sites in Israel. Judging by the ruins of palaces and temples, a water system and many cuneiform documents, the book of Joshua was correct in describing Hatzor (also spelled “Hazor”) as the “head of all the Canaanite kingdoms” in the period of 1800-1200 BCE. Ancient scribes came for training at Hatzor, a major center for administration and scholarship in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. Here in 2010, Hebrew University archeologists discovered two fragments of a legal tablet written in Akkadian from the same time period as the famous Hammurabi Code. The contents were similar – referring to personal injury law, slaves and masters. They also found the first Iron Age basalt workshop ever discovered in the Middle East.

• Tel Dan

Tel Dan stele fragments

In the mid-1990s, three fragments of a large stele (inscribed stone) with an Aramaic inscription were found at this northern site, probably constructed by Hazael, king of Damascus, when he conquered the Dan region in the ninth century BCE. The first royal inscription ever found in Israel, the stele describes the victory of a king of Aram over “the king of the House of David,” making it the earliest reference to the Davidic monarchy outside of the Bible, and it fills in aspects relating to stories recounted in the biblical text about encounters between Arameans and Israelites. Tel Dan has also revealed treasures such as flint tools and primitive pottery; stone ramparts and houses, metallic pottery and seal impressions; a mudbrick gatehouse from the 18th century BCE; grain storage pits and an oil press from the Iron Age; a bilingual Greek and Aramaic inscription; and a wine press, irrigation pipes, fountain house, Venus statue and coins from the Roman period.

• Tel Rehov

Tel Rehov, where ancient beekeepers made honey and wax

Here in the Beit Shean Valley, Hebrew University excavators found evidence in 2007 of a major Iron Age (biblical era) honey production facility. Maeir calls it “an absolutely unique find, because until now it was assumed that the honey referred to in ‘the land of milk and honey’ was date honey, but here’s clear proof there were bee hives at that time.” Most likely, wax was also produced here commercially. The 30 intact hives arranged in orderly rows, and remains of up to 200 more, were made of straw and unbaked clay. There were even remains of bees, bee larva and pupae. By studying the DNA from these remains, researchers in 2010 determined that these bees were similar to the Anatolian species in modern Turkey. Indeed, an Assyrian stamp from the eighth century BCE shows that bees had been brought 400 kilometers from southern Turkey. Tel Rehov, one of the largest Iron Age sites in Israel, has also yielded some of the largest collections of Greek pottery from the 10th to ninth centuries BCE found in Israel, along with clues as to the chronology of events in early Israel’s monarchy. • Mishmar David In 2006, the IAA found evidence of a large ancient settlement at this central Israel site, dating from the Early Islamic to Crusader periods. Both Christian and Muslim symbols were found, such as crosses on clay lamps and inscriptions in ancient Greek that mention “the mother of God,” as well as bronze coins struck with the Arabic inscription, “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his servant.” The highlight was the discovery of a unique round Byzantine-Islamic stone structure paved with a colorful mosaic decorated with geometric patterns and a palm-tree motif. It might memorialize a religious martyr, a miracle that occurred at the site or a visit by a saint. The archeologists also found ruins of an industrial zone for the large-scale production of wine.

• Ramla

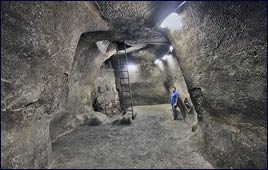

An underground eighth-century reservoir at Ramla

Photo courtesy of Israel Tourism Ministry

Built in the early eighth century on sand dunes about nine miles southeast of today’s Tel Aviv, Ramla was the only city in ancient Palestine founded by Arabs. Most of its buildings were lost, but archeologists have been reconstructing the remains of the Umayyad-period White Mosque, with its distinctive minaret, since 1949. In the 1990s, they unearthed an ancient dye factory as well as underground reservoirs and cisterns, and a trove of glass, coins and jar handles stamped with Arabic inscriptions. In May 2006, a cement quarry bulldozer serendipitously broke into what turned out to be the second largest lime cave in Israel, on the outskirts of Ramla. Inside were several previously unknown species of invertebrates including 10 eyeless scorpions and seven species of crustaceans and springtails.

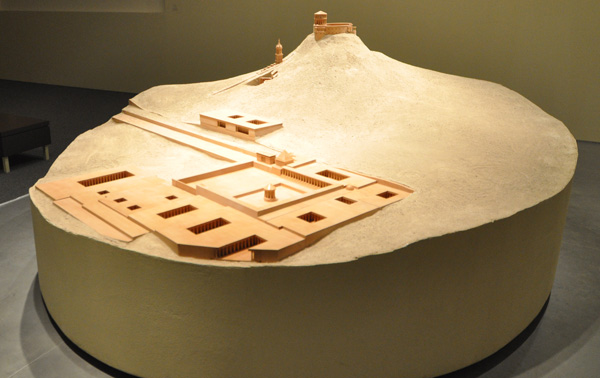

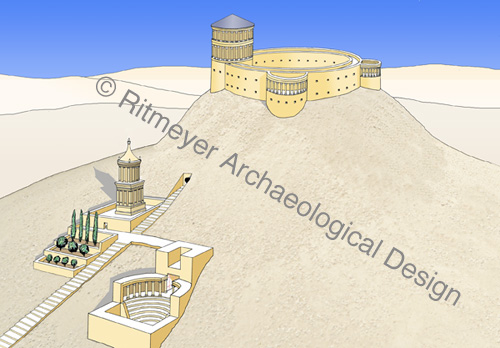

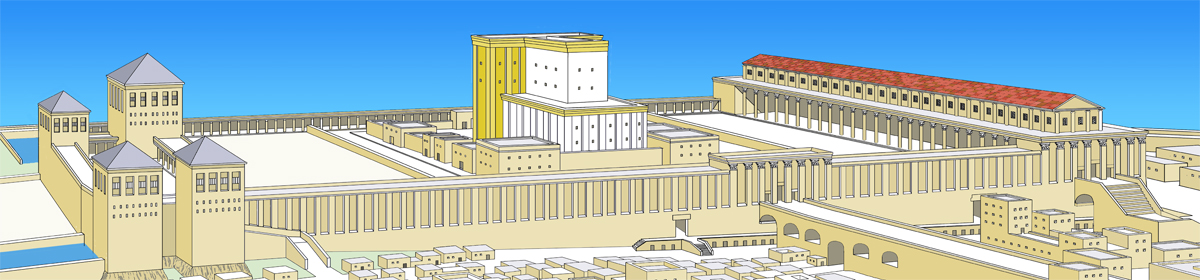

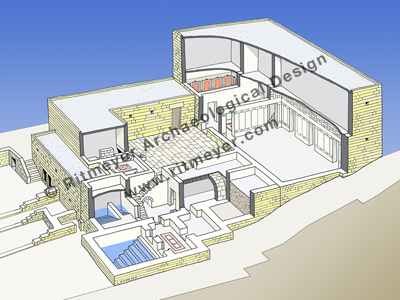

• Herodion The 2007 discovery of the remains of Herod the Great’s tomb made international headlines. Maeir explains that archeologists had been searching for the gravesite for decades. Although it was partially destroyed, with the body of the king stolen by ancient grave-robbers, it was nevertheless clear what Hebrew University’s Ehud Netzer finally came across, following 35 years of excavations at Herodion (also called Herodium) in the Judean Desert. Herod (74 to 4 BCE) was the Roman client king who built expansively throughout Israel, most notably the Second Temple in Jerusalem, Caesarea and Masada. Roman historian Josephus Flavius wrote that Herod was buried near his two palaces and gardens at Herodion, one of the largest royal sites in the Roman-Hellenist era, but nobody had ever found it. The Israelis weren’t able to get to the site, sometimes described as an ancient royal country club, until after the 1967 Six-Day War. Archeologists unearthed many interesting architectural features at the site, which later served as the seat of the Roman governors, as a hideout for rebels during the Bar Kochba Revolt (see Te’omim Cave), and even as a Byzantine leper colony. Click here for a video tour of Herodion

• Yiftach-El

Flint scraper and flint chips found at Yiftach-El

A cache of 9,000-year-old flint blades was among the latest Neolithic (9,000-8,700 BCE) treasures unearthed at this large Lower Galilee site that was once an important Crusader city. Flint blades were rare in Neolithic times, as people started to transition from a nomadic shepherding existence to a more settled agricultural life. The collection – which was probably used for barter — includes 80 blades, eight arrowheads, three lumps of flint, two sickle blades and two bone implements. They were concealed under the floor of a building, discovered in 2008 during the construction of a new traffic interchange at the nearby Movil Junction.

• Tel Kabri

Located in the western Galilee near Akko (Acre) and the resort town of Nahariya, Tel Kabri has the earliest-known Western art found in the Eastern Mediterranean. Excavations focus on a palace dating from around 1600 BCE, which contains a Minoan-style floor and wall frescoes uncovered over the past 25 years. “This is a unique find that tells us about international trade and culture connections,” says Maeir. He explains that frescoes of this style represented the Minoan culture of Crete, pointing to a direct link with their neighbor to the south. • Hilazon Cave

Entrance to the lower Hilazon Cave

The body of a sorceress or witch doctor from the Epi-Paleolithic period (16,000 to 8,300 BCE) was found buried in a cave at this Western Galilee site, giving it the nickname of the Shaman Cave or Witch Cave. There were also 28 skeletons of men unearthed here, but the shaman is of particular interest because her body was methodically surrounded by 50 turtle shells, bones of a leopard and wild boar, a human foot, a cow tail, two martens (an animal related to the badger) and a golden eagle’s wings, providing a fascinating picture of the social and cultic practices of this period. • Te’omim (Twins) Cave

Entrance to the Te’omim Cave

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Rebels against the Roman occupation once hid out in a series of natural caves in the Jerusalem hills east of Beit Shemesh, including the Te’omim Cave. In a recently discovered continuation of this cave, archaeologists found artifacts from the 132-136 CE Bar Kokhba Revolt, such as silver and bronze coins, weapons, pottery storage jars and oil lamps. Filled with stalactites, stalagmites and bat colonies, the cave also had human bone fragments — indicating that at least some of the rebels never made it out alive. It’s called Twins Cave, by the way, because legend has it that a 19th century barren woman drank water dripping from the cave’s ceiling and subsequently gave birth to twins. But, thanks to the resident bats, it’s also sometimes called the Bat Cave.

• Khirbet Qeiyafa

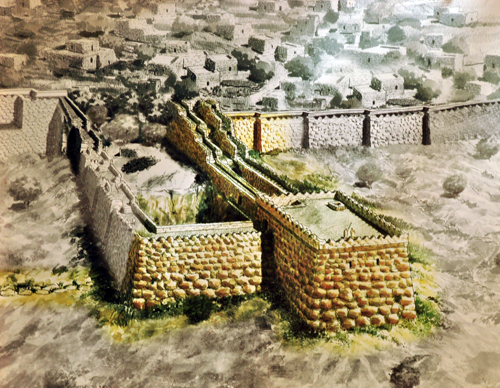

A view of the Khirbet fortress

Photo by Yoav Dothan

Located on the hills bordering the Elah Valley, this six-acre strategic fortress is circled by a 700-meter long wall of eight-ton stones. Here, along the main road from Philistia and the coastal plain to Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Hebron, the young David felled the giant Goliath with stones from his slingshot. Excavations began only in 2007, yielding evidence of David’s kingdom and also the earliest Hebrew inscription from a clear context. The two major layers of this tel date from the Iron Age and the Hellenistic era, with shards discovered from the Bronze Age as well as from the Persian, Roman, Byzantine, early Islamic, Mameluke and Ottoman eras.

• Tel es-Safi

Tel es-Safi siege system

Otherwise known as Gath, the hometown of the biblical giant Goliath, this tel has been under excavation since 1996 and still yields treasures such as the world’s oldest known siege system; the earliest metal production area for iron and bronze ever unearthed in Philistia; and a large stone Philistine altar built to the exact dimensions of the Israelite altar in the desert Tabernacle as described in the Bible, except that it has two “horns” rather than four. Maeir’s team is aided in its work at Tel es-Safi by the Kimmel Center for Archeological Science at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, which provides a portable field lab at the excavation site and another lab at the base camp to facilitate more intricate analyses of the day’s finds. The results help archeologists decide on the day’s excavation strategy and provide an integrated perspective on the past, says Maeir.

• Ramat Rachel

The ancient dovecote (columbarium) at Ramat Rachel

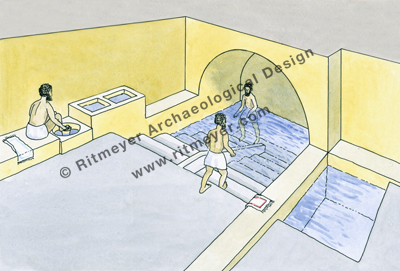

An ancient water reservoir was uncovered here in 2010 with the aid of a 250-ton crane to remove the five 10-ton rocks forming the collapsed top of the cave in which the water was stored. Now a kibbutz/conference center on the southern outskirts of Jerusalem, Ramat Rachel was first settled in the days of the Judaic monarchy during the eighth and seventh centuries BCE. It was home to Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and early Islamic settlers, and then lay abandoned for about 1,000 years until Jewish pioneers rebuilt it in the 1930s. A luxurious Assyrian palace, a Roman villa, a bathhouse, gold coins from the Second Temple period, a dovecote and a Byzantine church are also among the finds here.

• Omrit

Omrit, on the western side of the Golan Heights near the Hula Valley, is an exceptionally well-preserved site along the ancient Roman road to Damascus. It was hidden for millennia until a 1998 fire exposed it. Among the finds there so far are two limestone podiums from a Roman temple; a Byzantine olive oil factory; a winepress; shops; a colonnaded road; and a bath complex constructed after the collapse of the temple in an earthquake in 363 CE. Because a first- or early second-century Roman temple is a rare find in Israel, Omrit will probably be preserved as a national park for tourists to get a glimpse of what political and cultural life was like in those days.

• Khirbet Wadi Hamam

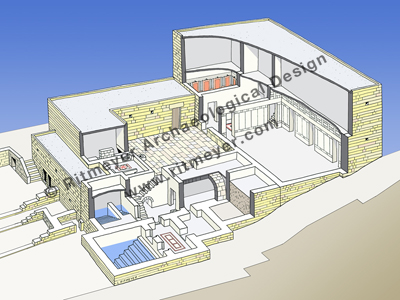

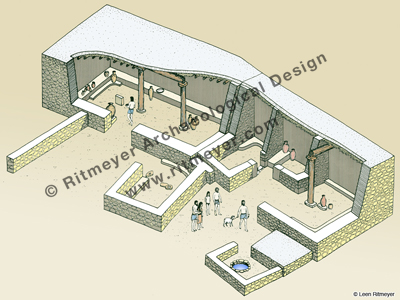

Benches in the Khirbet Wadi Hamam synagogue

This Roman-period village in the eastern Lower Galilee just west of the Sea of Galilee was first excavated in 2007 and holds the key to dating the many synagogues found in this area. Most Galilee villages had their own Jewish houses of worship, many featuring intricate mosaic floors, but the one found at Khirbet Wadi Hamam is particularly well preserved and wider than most. It depicts craftsmen at work, a scene found in no other mosaic of the time period. Made of limestone and basalt, this synagogue had two rows of benches and three rows of columns holding up a tiled roof.

• Jaffa

The ancient port city just south of Tel Aviv has a long but little understood history that archeologists are starting to piece together from finds gathered mainly since 1997 in excavations led by Tel Aviv University. Jaffa was an ancient Egyptian administrative center, as evidenced by the ruins an Egyptian citadel and “Lion Temple” harboring a lion’s skull. A huge royal scarab found there bears an eight-line inscription in hieroglyphics declaring that by the 10th year of his reign, Amenhotep III (pharaoh of Egypt in the 14th century BCE) had successfully hunted 102 lions. Archeologists also found the concrete remains of a 19th century BCE house with a bench in a paved area inside that may have been a kitchen, since next to it they found a plastered niche containing 12 Egyptian bowls. |