We are pleased to say that we are back online after a week of outage. Will post soon again.

Category: Jerusalem

Understanding The Holy Temple Jesus Knew

Carta, the well-known Jerusalem publishers, offers an introductory price on our latest, and eighth, Carta book, valid until June 30, 2017 (make sure to put in the discount code: “25-off”):

This title is part of the “Understanding” series of Carta: Continue reading “Understanding The Holy Temple Jesus Knew”

Virtual Jerusalem

Two new apps have been developed to help visitors visualize ancient Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount. The BYU has developed a free app, which can be downloaded here.

The Virtual New Testament app is one of the most accurate digital recreations of first-century Jerusalem. It’s purpose is to enhance scripture study by allowing you to experience the city, engage with the environment, and immerse yourself in the world of Jesus’ mortal ministry.

This app works for both Mac and Windows desktops and can be downloaded for mobile devices at the Apple App Store or at Google Play.

The Jewish News Online reported on another app that was developed by Lithodomos VR. This app only costs a couple of dollars and is worth getting if you have a Virtual Reality headset. An introduction can also be viewed on YouTube.

Young and old alike now have the chance to wander the streets of ancient Jerusalem, after archaeologists recreated the city at the time of King Herod in a virtual reality headset.

Half a million pounds of investor funding helped created the Android app, called Lithodomos VR, based on the archaeology of Temple Mount in 20BC, before it was destroyed some 90 years later.

The app (at £1.59 or S2.00) and headset let the user experience market streets, the Western Wall, the temple precinct, and the Jewish and Roman period districts, with buildings virtually reconstructed based on the latest archaeological evidence.

Twelve-year-old Jesus in the Temple at Passover

On Sunday, the 10th of April, 2017, the Jewish people begin celebrating Pesach – Jewish Passover. That is one week earlier than Easter. However, in this blog post we would like to remember the time that Jesus as a twelve-year-old visited the Temple during Passover for the first time in his life.

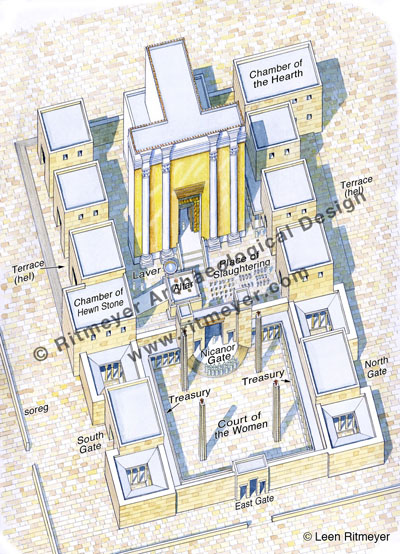

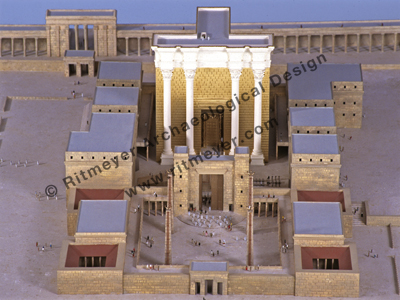

The Temple in the time of Christ was a magnificent building. From the Temple Court (azarah), 12 steps led up to the Porch that was as high as the Temple itself. In front of the entrance to the Sanctuary, a Golden Vine was attached to four columns.

No wonder that some of Jesus’ disciples remarked “how the Temple was adorned with beautiful stones and with gifts dedicated to God” (Matthew 24.1; Luke 21.5).

The central feature of this complex, the Holy of Holies, was located deep inside, at the west end of the Sanctuary. No one could enter this place of utmost sanctity but the High Priest once a year on the Day of Atonement. A veil separated the Holy of Holies from a place of lesser sanctity, the Holy Place.

The Temple Court lay in front of the Temple and it contained the Altar, the Laver and the Place of Slaughtering (or Shambles). This was the closest court to the Temple and out of bounds to anyone like Jesus who was not a priest.

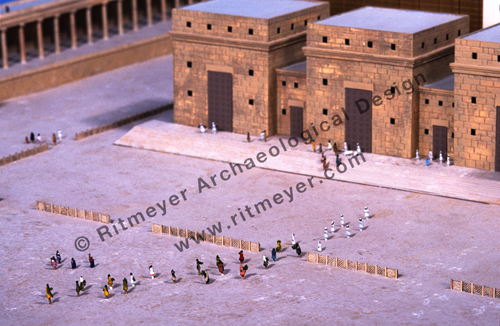

This Temple Court was separated by the Nicanor Gate from the Court of Women, which lay to the east of the Temple. Buildings, called gates, surrounded this complex. In front of the gates was a terrace (ḥel – pronounced chel with the “ch” sounding guttural as in the Scottish “loch”) of 10 cubits wide, which was reached by a flight of steps of half a cubit high and deep. This terrace bounded the wall of the gate buildings on their southern, western and northern sides.

It is on this ḥel that we get our first glimpse of Jesus after the birth narratives in the Gospels. Scripture is silent about his youth although it is clear from the observations of nature and Biblical history later attributed to him by the Gospel writers that he absorbed every spiritual and historical lesson that was provided by his upbringing in the countryside around Nazareth.

Now he was twelve years of age and his first words are recorded for us (Luke 2. 41-52). Under the law, attendance at the feasts in Jerusalem was obligatory for boys from the age of thirteen, a birthday that was a milestone in the life of a Jewish boy, when they became a Son of the Commandment or Bar Mitzvah. In practice, this legal age was pushed forward by one or two years so that Jesus, after he had passed his twelfth year, came up to Jerusalem for the Passover with his family. Jesus’ first view of the Temple must have filled him with a great sense of the purpose he had been developing during the quiet years in Nazareth. Attendance at the Temple was obligatory only for the first two days of Passover, after which many of the pilgrims would have returned home again. It would appear that Joseph and Mary and their “company” did indeed start to return home and had travelled for a day. When they finally realized that Jesus was missing, it took them three days to find him and when they did, he was “in the temple, sitting in the midst of the doctors, both hearing them and asking them questions.” The ḥel is the only place in the Temple he could have been.

We learn this from a tractate of the Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 88b, which tells us:

“It has been taught; R. Jose said; Originally there were not many disputes in Israel, but one Beth din of seventy-one members sat in the Hall of Hewn Stones, and two courts of twenty-three sat, one at the entrance of the Temple Mount and one at the door of the [Temple] Court, and other courts of twenty-three sat in all Jewish cities.” “The Great Sanhedrin] sat from the morning tamid (daily sacrifice) until the evening tamid [in the Hall of Hewn Stones]; on Sabbaths and festivals they sat within the ḥel.”

So, Passover would have been one such festival when members of the Temple Sanhedrin would come out to teach in this area. Ordinary people, who normally had no access to the classrooms where young priests were taught, could come and question them. Jesus must have eagerly made use of this opportunity and never would they have had such a sharp student as him. During this visit to the Temple, he would have seen the preparations for sacrificing the Passover lambs and realized, perhaps for the first time in his young life, that the entire ritual pointed forward to his own sacrifice. He would have been so absorbed by all these experiences that he would not have wanted to leave. He forgot about his natural family, for here he was at home – in his Father’s house.

A Capital from Solomon’s Porch on the Temple Mount

The Israel Hayom newspaper reported yesterday that a capital of the 2nd Temple era has been found by the Temple Mount Sifting Project (TMSP).

Photo credit: Vladimir Naychin

The capital of a carefully-adorned column that stood on the Temple Mount in the time of the Second Temple has been discovered through the Temple Mount Sifting Project.

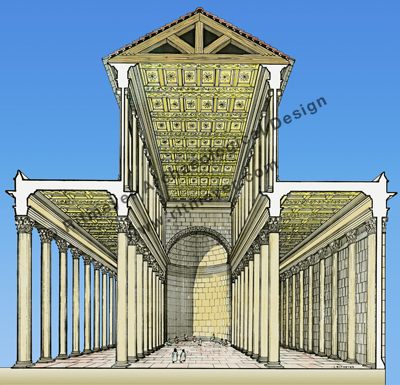

The capital, whose size indicates that the column had a circumference of 75 centimeters (30 inches) at its top, is a section of one column that formed part of the double colonnade that surrounded the Temple Mount plaza.

Dr. Gabriel Barkay, the director of the Temple Mount Sifting Project, said that “this is a capital in the Doric style, one of the characteristics of the art in the time of the Hasmonean dynasty. This appears to be the capital of a column formed part of the eastern colonnade of the Temple Mount, which Josephus and even the New Testament called ‘Solomon’s Porch.’ A column like this is impressive testimony of the immensity of the structures on the Temple Mount in the Second Temple era, and fits in well with Josephus’ narrative, which describes what he saw with his own eyes.”

Barkay explained that a 25-cubit column would have stood 12.5 meters (41 feet) high.

It is of course wonderful news that a capital of a column that most likely stood on the Temple Mount was found. I would agree with Barkay that the capital could have belonged to one of the columns that formed the eastern Hasmonean (pre-Herodian) colonnade. This colonnade was indeed known as Solomon’s Porch, where Jesus walked during Hanukkah (John 10.23). It was also the place where Peter and John healed the blind man (Acts 3.11) and where the apostles did many signs (Acts 5.12).

One must, however, be careful with dimensions. In the article it says that the circumference of the Doric column that supported the capital was 75 cm. That is probably a mistake. According to simple mathematics, a column with a circumference of 75 cm (30 inches) has a diameter of less than 24cm (9 inches). In ancient architecture, Doric columns had a 1:8 ratio between diameter and height. According to that rule, this column could not have been higher than 2m (6 feet, 6 inches), which would not have been exactly monumental. Barkay therefore probably meant that the column had a diameter of 75cm. In that case, the column would have been about 6m (20 feet, 11.4 cubits) high. Barkay estimated that a 25-cubit column would have stood 12.5 meters (41 feet) high, but this one would have much smaller, about half the size.

An additional problem is the use of units of measurement by Josephus. In War, he uses cubits and in Antiquities (Roman) feet. As a rule, his measurements in feet are more accurate than those in cubits, which are often exaggerated.

Josephus writes in War 5.190-192, that the columns of the Herodian porticoes were 25 cubits, which according to the Royal Cubit of 52.5 cm (20.67 inches), would be 13.12m, (43 feet) high, but in Ant. 15.413 he says that the columns of the porticoes were 27 feet high (8.23m, 15.67 cubits). Let us first look at the 25 cubits high columns and then at those of 27 feet high.

According to the Doric ratio of diameter and height, the diameter of a 25 cubit high Doric column must have been 1.64m (5 feet, 5 inches). Archaeological remains of parts of such thick columns have been found in secondary use in the Temple Mount excavations in front of a gate of an Umayyad palace. A complete column with a diameter of 1.46m (4 feet, 9 inches) has been preserved in the Double Gate underground passageway. Josephus mentions in Ant. 15.415 that the height of the Corinthian columns (which have a ratio of 1:10) of the Royal Stoa were 50 feet (15.24m or 29 cubits) high, probably including the capitals. This measurement is somewhat similar to the 25 cubits high columns of War 5.190-192 and must therefore relate to the columns of the Royal Stoa and not to those of the porticoes. Columns of that height could only have belonged to the Royal Stoa.

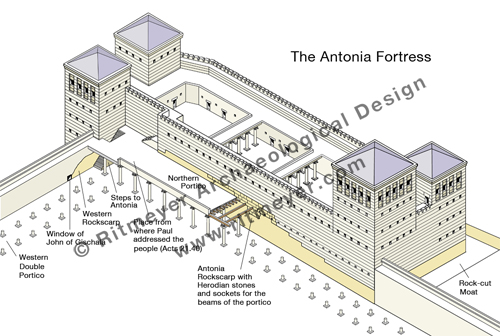

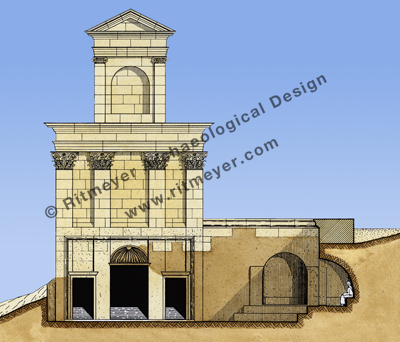

Going back to Ant. 15.413, where Josephus writes that the columns of the porticoes were 27 feet (8.23m) high, we found that this measurement is indeed correct for the Herodian porticoes. The preserved sockets of the northern portico can still be seen in the south wall of the Antonia Fortress (see drawing). They are located 8.84m (29 feet) above ground level. As the beams that were laid on top of the capitals were fixed in these sockets, Josephus’ measurement of 27 feet appears to be accurate.

The reconstructed height of the newly found Hasmonean column of 6m (20 feet) is a little lower than those of the Herodian columns. The older Hasmonean portico, also known as “Solomon’s Porch”, was apparently not as high as the Herodian colonnades, as indicated in this reconstruction model.

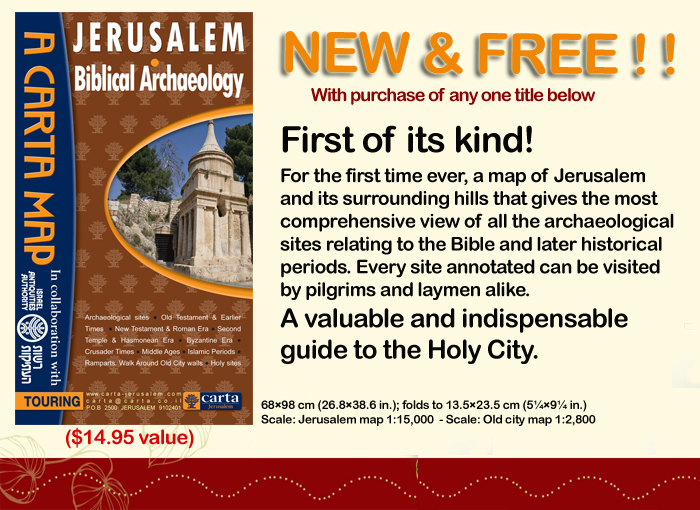

Jerusalem Biblical Archaeology Map by Carta

There was much excitement in our house last week when the Biblical Archaeology Jerusalem Map by Carta (see previous post) arrived.

Spreading the chart out on the table, we were able to retrace many of the trips and explorations we made when living in Jerusalem. At the time, some of these had required poring over Ordnance Survey maps and reading archaeological reports before we could identify the sites involved. Now, with the acquisition of this map, we can easily find the location of these sites, as well as, and most importantly, the latest sites to have been discovered.

Twenty-three years ago, the publication of the New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, a a joint venture by the Israel Exploration Society, Carta, and Simon and Schuster’s Academic Reference Division, was a landmark in the quest to provide a comprehensive work that would summarize the results of archaeological work in the Land of Israel for the English reader. It had a 102-page long section on Jerusalem. Ephraim Stern wrote in the Editor’s Foreword to the Supplementary Volume, published in 2008:

“Since the publication in 1993 of the four volumes of the New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (NEAEH) archaeological excavations have continued at a staggering pace. Many of the entries of those four volumes quickly became outdated and the need arose for this volume, which updates the NEAEH to the year 2005. It is a joint venture of the Israel Exploration Society and the Biblical Archaeology Society.”

So, while we await the next update, a mammoth undertaking, this handily portable map will play a vital role in guiding the visitor around the archaeological sites of Jerusalem,

The front part of this large map (63×94 cm, or 25×37 inches) shows the Old City and its surroundings, while the reverse side is dedicated to the Old City in much greater detail. The map was made in collaboration with the IAA (Israel Antiquities Authority, or Reshut Atiqot in Hebrew), with the text and scientific advice provided by Dr. Yuval Baruch. The archaeological sites are described in small text boxes with an arrow pointing to the exact location of each.

Most of the sites on the front part are familiar to us, but by no means all of them are. It is good to see the site of Lifta on the northwest of the city included. This has been identified as the site of the Waters of Nephtoah of Joshua 15.9 and 18.15, defining here the border between Benjamin and Judah. We remember exploring the village and its spring in the 1970’s, but then it seemed very much off the beaten track, being hidden away on two steep slopes in the last valley of the ascent into Jerusalem.

There are other sites we are not so familiar with such as Khirbet Adaseh North and Khirbet Adaseh, 2 miles to the southeast. Adasa, was, of course, the place where the Maccabees were victorious in their battle against the Seleucid general Nicanor, who lost his life there.

The Old City map is also informative with sections dedicated to the Kidron and Hinnom Valleys, Mount Zion, the City of David and the Aqueducts of Jerusalem. We are pleased that the Tomb of Annas the High Priest, a site we were able to identify in the early 1990’s, is included among the sites in the Hinnom Valley.

A glaring omission on this side of the map is any detail on the vast platform of the Temple Mount. However, giving the impression that the site is a terra incognita is part of the political reality in this area. Only some of the gates are mentioned, with the Double and Triple Gates unfortunately still called the Huldah Gates. The original Huldah Gates were in fact located in the southern wall of the pre-Herodian Temple Mount some 72 m (240 ft) north of the present Southern Wall.

No reference is made to the Step, which is the remains of the Western Wall of King Hezekiah’s Square Temple Mount or of The Rock, identified by many as the site of the Holy of Holies of Solomon’s Temple. The many well-heads visible on the platform indicate the location of the many underground cisterns, of which two, Cisterns 6 and 36, may have been mikva’ot. These would also have added interest to this part of the map.

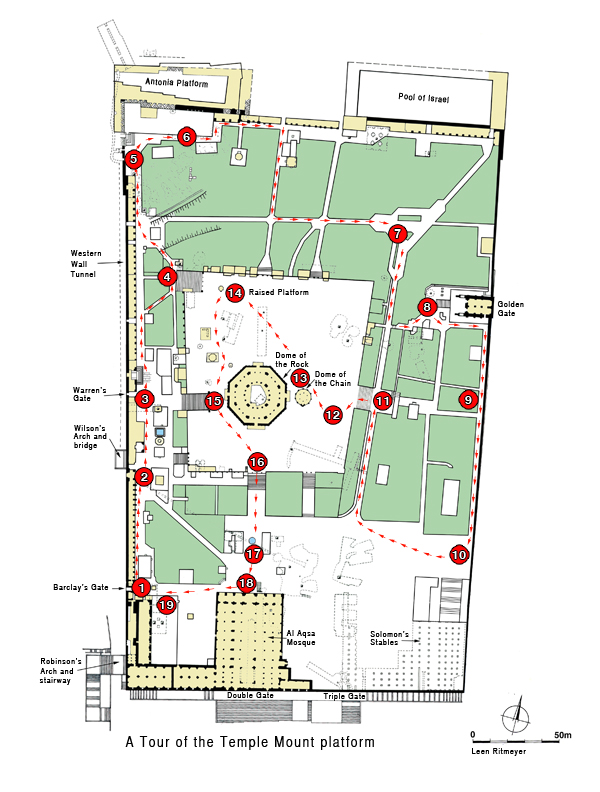

Information on the Temple Mount platform is, however, available in our guide book Jerusalem, the Temple Mount in which we have produced a map showing 19 points of archaeological and historical interest:

Despite these shortcomings, however, we foresee copies of this map being given as presents for those who love exploring the Old City of Jerusalem and its environs. And if you have friends visiting who have been to Jerusalem, framed reproductions are bound to stimulate some lively conversation.

Special Offer from Carta

Carta Jerusalem offers the new Jerusalem – Biblical Archaeology map for free with the purchase of one of three books mentioned below, including The Quest. In addition, each of the three titles can be purchased for 20% off the list price, i.e. $48.00 instead of $60.00. This excellent offer, which saves you almost $27.00 is valid until the 31st of January, 2017. When ordering, all you need to do is click on the Voucher code: 20-OFF, and the map will be added for free.

The three titles are:

Flooring from the Temple Mount in Jerusalem

The discovery of colored floor tiles found in the Temple Mount Sifting Project, that apparently came from the Herodian Temple Mount was announced during the 17th Annual Archaeological Conference in the City of David National Park held on the 8th of September 2016. This new find received plenty of media coverage, see for example this Jerusalem Post report. As usual the reporting took the form of copying and pasting the original report.

First of all, kudos to Frankie Snyder for having patiently fitted these many pieces together into meaningful designs. The stones have different geometrical shapes, were finely cut and polished and fitted tightly together to create beautiful designs. Such floor designs are called opus sectile, which is Latin for “cut stone”.

I wanted to be sure, however, that what was presented could indeed have belonged to floors or pavements on the Temple Mount. When I first saw the pictures of Frankie’s floor designs, they reminded me of the beautifully designed tiled floors of the late nineteenth century house in Ethiopia Street in Jerusalem where we used to live. These floor designs have been used for a very long time. For example, many pieces of Crusader and earlier stone floor designs were found during the sifting, see here.

Looking at the photographs presented by the TMSP, however, I wondered why some tiles looked like marble:

Hardly any marble was imported into Israel until the time of Hadrian. In 135 AD, he established a Roman colony called Aelia Capitolina, on the ruins of Jerusalem, which had been destroyed in 70 AD. Evidence of the use of marble has been found from this period. For example, in the Temple Mount Excavations a Roman bath house with a marble-lined pool was uncovered, together with a marble statue.

So, I asked Frankie what materials these reconstructed tiles were made of, she replied that, apart from locally sourced stone, different types of imported marble were also used, such as giallo antico from Tunisia, breccia corallina from Turkey, breccia di Settebasi from Greece and also alabaster from Egypt.

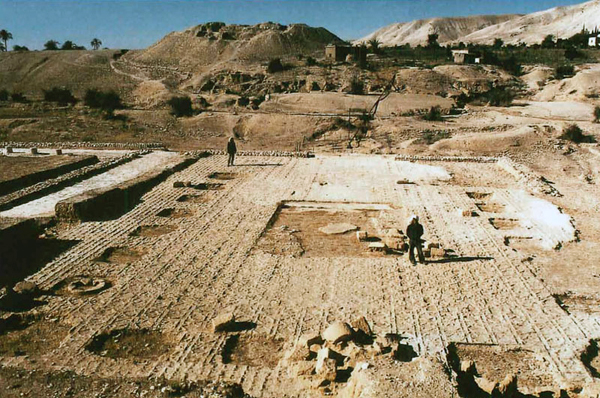

It was interesting to find out that the opus sectile pavement found in Herod’s Third Palace in Jericho also had pieces of marble worked into its design. Herod was a great lover of Roman art and architecture and apparently imported these tiles from around the Mediterranean.

Gabriel Barkay, one of the directors and co-founders of TMSP is sure of the Herodian date of the tiles they found:

“The materials of which they are made, colorful marble-like stones which originate from different locations and places around the basin of the Mediterranean. They were neither imported before the time of Herod the Great nor later, so we are sure of the date … Opus Sectile flooring is consistent with the style of flooring found in Herod’s palaces at Masada, Herodium, and Jericho, among others, as well as in majestic palaces and villas in Italy during the time of Herod. The tile segments, mostly imported from Rome, Asia Minor, Tunisia and Egypt, were created from polished multicolored stones cut in a variety of geometric shapes.”

Indeed, an opus sectile floor was found in the Peristyle Building in the Jewish Quarter Excavations. This was made of black bitumen and cream and red colored limestone.

The question that remains unanswered is, where on the Temple Mount were such floors laid? The description of Josephus in War 5.193 was quoted: “The open court was from end to end variegated with paving of all manner of stones.” Does this refer to these opus sectile floors?

Herodian paving on the Temple Mount has been identified by us and reported on previously. These in situ remains show that the open courts of the Herodian Temple Mount were paved with very large and thick paving slabs made of local limestone, very similar to those laid in the streets that surround the Temple Mount.

All the known opus sectile floors were laid indoors and not outdoors. These delicately constructed floors would not have survived long outside in the sometimes harsh Mediterranean climate. We suggest therefore that they came from the interior of some of the many buildings that surrounded the Temple and/or from under the colonnades around the smaller courts.

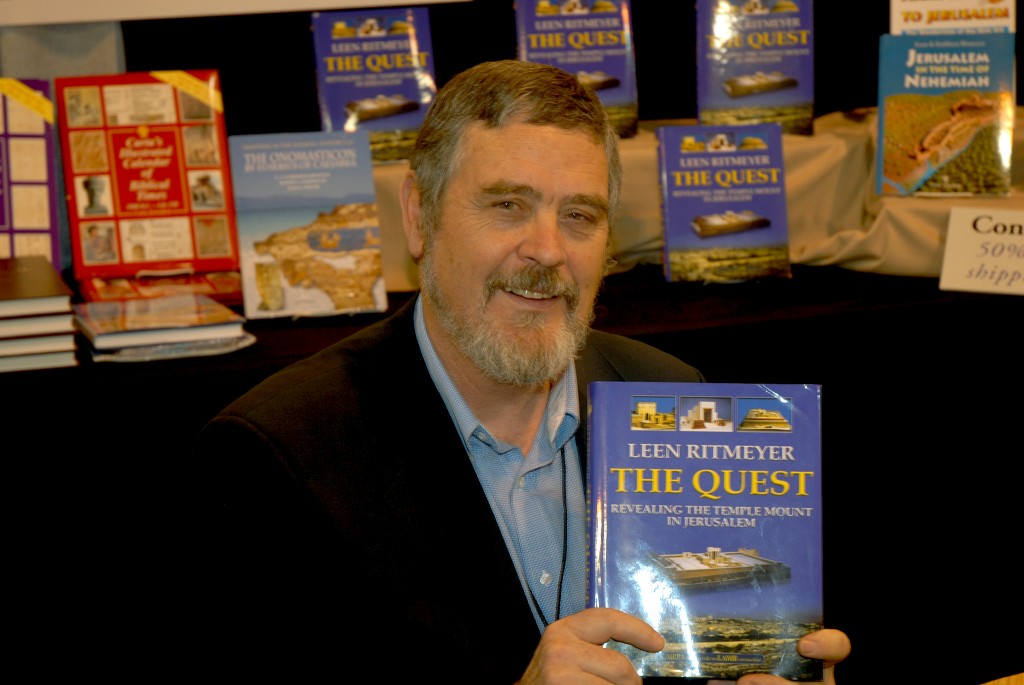

10th Anniversary of The Quest

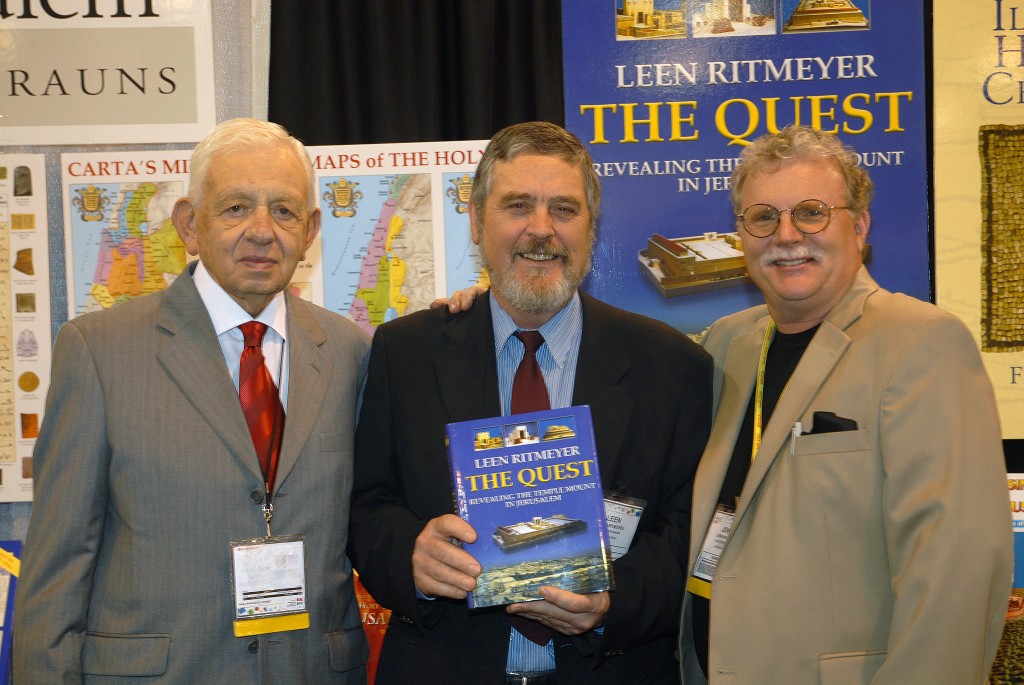

In July 2006, my book The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem was published. The launch of The Quest took place at the International Christian Retail Show in Denver, USA.

I don’t know who was more excited to see this book in print, John E. Mancini of the Lamb Foundation who had sponsored me to write this book, Emanuel Hausman, Chairman of Carta Publishing in Jerusalem, or myself.

I dedicated the book to “John E. Mancini for sharing the vision to let the ancient stones tell their story and his unstinting support of The Quest.” We first met in Albuquerque, where Dr. Steven Collins, asked me to lecture on a regular basis as adjunct-professor at Trinity Southwest University in Albuquerque, NM, which he heads. I wrote this in the preface of The Quest:

For several years, Dr. Collins and I led tours to Israel. One participant, John E. Mancini, who with his wife Chris attended all our seminars and tours, expressed great interest in my research and was keen to make this material publicly available. John had already set up the Lamb Foundation to help Trinity and other projects, and during the fall of 1999 offered to help publish this book on the Temple Mount. I am delighted to thank him for the opportunity he gave me to devote myself to the presentation of my research carried out from the start of my archaeological career on the Temple Mount excavations in 1973. Thanks to John E. Mancini, to whom the book is dedicated, and all those who aided and accompanied me on this long and arduous journey, the public at large can now partake in the extensive documentation of Temple Mount history and archaeology provided by this volume and evaluate the proffered solutions to vexing questions.

Kathleen and I have experienced how pleasant it is to work with Carta, the Jerusalem publishers, on a number of publications. This book has, however, been a much more elaborate project. My thanks to all the people at Carta, their superb management and meticulous attention to the many details demanded by this title, especially to Barbara Laural Ball for her sensitive editing and general supervision of the project. Their proficiency can be seen on every page.

Ten years later, the book is still in demand and sells well and we have had many positive comments and favourable reviews. Yesterday, the 4th of July 2016, our book was chosen by the Temple Mount Sifting Project to top their list of the “10 Books To Read If You’re Into Archaeology and Israel” (even before the Hebrew Bible!).

This list was created by the staff of the Temple Mount Sifting Project in honor of their Book Week Campaign. It includes everything you need to know about Israel, Jerusalem, archaeology, and the Temple Mount.

1. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem

This book is by Leen Ritmeyer. The recommendation was fought over by Gaby Barkay and Frankie Snyder. We will give them both credit.“No book is better suited to the study, understanding and development of the manmade plateau that is the focus of the world s interest the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Ritmeyer’s experience as architect of the Temple Mount Excavations following the Six-Day War, coupled with his exploration of parts of the mount now hardly accessible and his doctoral research into the problems of the Temple Mount make him singularly qualified for the task.”

The other books on the list look very interesting too!

Underground Jerusalem

Nir Sasson wrote a fascinating article in Haaretz on the underground excavations taking place in Jerusalem.

Jerusalem has vastly expanded in the 7,000 years of its existence. Including, in the past two decades, downwards. Beneath the Old City, one can already walk hundreds of meters underground, pray in subterranean spaces of worship and see shows in subterranean caverns and halls. There are plans in place to dramatically increase this area – essentially, restoring the true ancient city beneath the visible one.

The article is accompanied by excellent plans, photographs and videos to bring you up to speed with what is happening underground. Despite protests from the Palestinians, who deny that the Jews have any historical connection with the Temple Mount, these digs do not penetrate below the Temple Mount.

Magnificent discoveries have been made in the City of David:

Near a 3,000-year-old fortification wall in the park’s center, or in the center of Silwan – depending on whom you ask, we descend underground through an iron door. It leads into a short tunnel that opens up into a series of rooms and halls. Here, in an area still closed to the public, fortification and water systems were discovered, mainly from the Canaanite period, or according to Jewish chronology – prior to the capture of the city by King David. Some have been known to science for over 100 years.

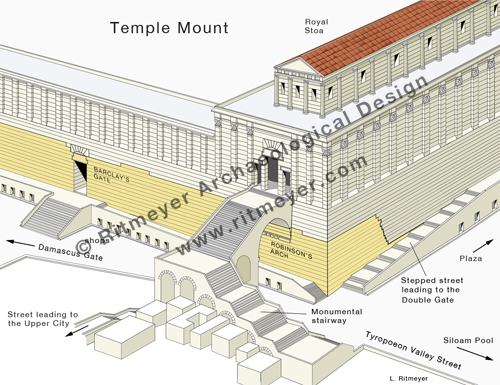

It is possible today to visit the underground remains in the City of David, see the Gihon Spring and walk through Hezekiah’s Tunnel that brings you to the Siloam Pool. From there one can walk underground through an ancient sewer below the Herodian street that leads up to just below Robinson’s Arch in the Temple Mount excavations, aka the Davidson Archeological Park. (see this video: 01_uknima)

A large stretch of the Herodian street had already been excavated above ground by the team of Prof. Benjamin Mazar in the 1970’s along the southern end of the Western Wall. The street that was found below Robinson’s Arch continues north to the Damascus Gate and south to the Siloam Pool in the City of David:

Before Mazar’s excavations, smaller parts of the same street had been excavated lower down in the City of David by Bliss and Dickie in the 1890’s, in the 1930’s by Hamilton and in the 1960’s by Kathleen Kenyon.

In the last couple of years, underground excavations have apparently expanded and uncovered the full width of the Herodian street for a stretch of 120 meters. The original width was 7.50 meters. New tunnels are being dug to connect this street with the Givati parking lot excavations and the new visitor’s centre planned in this area just south of the Dung Gate.

To the north of the Western Wall Plaza one can walk through the Western Wall Tunnel and see the many new areas that have been excavated.  The plan appears to be that in the future all these areas will be linked together, so that a “subterranean City of Jerusalem” can be visited.

The plan appears to be that in the future all these areas will be linked together, so that a “subterranean City of Jerusalem” can be visited.

Not everybody is happy about this development. One protester said:

“A huge excavation project is taking place here, hidden from the public eye, using outdated excavation methods. This is an excavation without boundaries and without any clear category, it’s not a research dig and not a rescue dig, it has no limit of time or place and no professional objectives.”

The excavation methods are not outdated, but these plans are very ambitious and politically controversial. However, once realised, a whole new experience is waiting for tourists to explore this “parallel universe” and enjoy a journey through “Underground Jerusalem”.