This is a question which used to be debated by scholars, but is now used by politicians to delegitimise the Jewish claim to Rachel’s Tomb, as reported in a previous post. The Palestinians are trying to deny that the disputed building near Bethlehem is Rachel’s Tomb, thereby denying their own traditions, up to 1996 that is to say, for political reasons. Israeli commentators on the right of the political spectrum insist on the historicity of Rachel’s Tomb, while others on the left don’t seem to care, doubting if Rachel ever existed.

I have no political axe to grind, but am interested in the geography of Biblical places, although the narrative is not always easy to understand. The Bible tells the story of Rachel’s giving birth to Benjamin and her subsequent death in Genesis 35. Jacob later sums it up in Genesis 48.7:

“When I came from Padan, Rachel died by me in the land of Canaan in the way, when yet there was but a little way to come unto Ephrath: and I buried her there in the way of Ephrath; the same is Bethlehem.”

Based on this text, it is clear that Rachel’s Tomb must be near Bethlehem and a little to the north of it, as Jacob came from that direction. This is further emphasised by Genesis 35.21: “And Israel journeyed, and spread his tent beyond the tower of Edar”. Migdal Eder in Hebrew means: The Tower of the Flock. This is picked up by the Prophet Micah 4.8,

“And thou, O tower of the flock, (Migdal Eder) the strong hold of the daughter of Zion, unto thee shall it come, even the first dominion; the kingdom shall come to the daughter of Jerusalem.”

According to Mishnah Shekalim 7.4, Migdal Eder was a place near Bethlehem where special flocks were kept from which lambs were taken for the Temple sacrifices on a daily basis. The next chapter in Micah states that the Messiah was going to be born in Bethlehem:

“But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, though thou be little among the thousands of Judah, yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel” (Mic. 5:2 ).

The connection between Bethlehem and Rachel remains strong in the story of the Massacre of the Innocents by King Herod, recorded only in the Gospel of Matthew (2.16). The evangelist sees the slaughter in Bethlehem as the fulfilment of Jeremiah’s prophecy: “In Rama was there a voice heard, lamentation, and weeping, and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not” ( 31.15).

Why did Jeremiah mention Rama in connection with the weeping of Rachel? In Jeremiah’s time, Rama was the place where the prisoners of Judah and Benjamin were gathered before they were carried away to Babylon (Jeremiah 40.1). Jeremiah was one of the prisoners, but was set free:

“Nebuzar-adan the captain of the guard had let him go from Ramah, when he had taken him being bound in chains among all that were carried away captive of Jerusalem and Judah, which were carried away captive unto Babylon.”

Rachel represents the Jewish nation in trouble, just as Rachel herself was when Benjamin was born. It does not mean that her tomb must be in Rama.

This last quote and the one in 1 Samuel 10.2, where Samuel tells Saul to go to Rachel’s sepulchre in the border of Benjamin at Zelzah, has prompted some scholars to locate Rachel’s Tomb to the north of Jerusalem. The location of Zelzah is unknown and the word does not appear as a place name anywhere else in Scripture. If it was a place name, it must have been on or near the border of Benjamin. The term ‘borders’ in the Bible is not to be understood as having fixed barriers as we have today. It denotes an area of influence that can shift over time. For example, Kiriath-jearim is located on the border of Benjamin and Judah. In the allocation of the Land to the tribes, Joshua 15.9,60 includes it in the portion given to Judah, while three chapters on, it is listed as one of the cities of Benjamin (Joshua 18.28). In this interesting fluctuation between Judah and Benjamin, Kiriath-jearim resembles Jerusalem, which is also variously described as belonging to one or the other tribe (Joshua 15.63; 18.28). At the time of Saul, the border may have shifted to the south and west of Jerusalem.

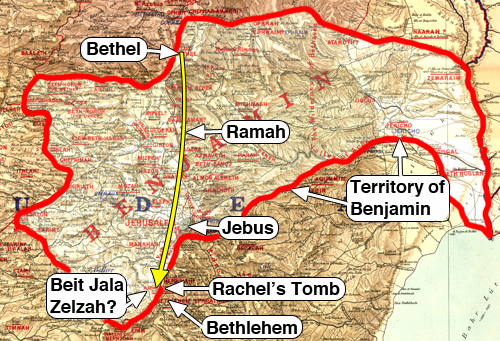

I came across a novel solution to the “border problem” and have tried to illustrate this (see map below). In my plan chest, I have a set of Palestine Exploration Fund maps published in 1880 with the tribal territories marked on. It also shows Rachel’s Tomb by its Arabic name of “Kubbet Rahil”. The map doesn’t agree with modern ones, but is interesting nevertheless. The territory of Benjamin is shown with the border west of Jerusalem (Jebus) further to the south. The mapping may have been influenced by the Irish missionary, Josias Leslie Porter, who wrote about Rachel’s Tomb in his “A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine,” (1858, p.74) “It is one of the few shrines which Muslems, Jews, and Christians agree in honouring, and concerning which their traditions are identical.” In referring to the nearby village of Beit Jala he asks, “Is this not the Zelzah mentioned by Samuel in sending Saul home after anointing him king in Ramah?” He then sketches out what for him must have been the southern border of Benjamin – “a crooked one it is true”. When he became president of Queen’s College in Belfast, he published “Jerusalem, Bethany and Bethlehem” (1886) in which his question about Zelzah was formulated as a statement!

I have used the PEF maps with the anachronistic territory of Benjamin marked out as a background to reconstruct the journey of Jacob and his family recorded in Genesis 35 (according to Porter).

If one could accept Porter’s sweeping statement that Beit Jala is Zelzah, it could work. Jacob travelled from Bethel in the north (vs. 16) over the main north-south road, passing by Ramah and continuing on the west side of Jerusalem (Jebus) and, after crossing what would later become the border between Benjamin and Judah at Zelzah, planned to travel to Bethlehem. It would place the location of the original Tomb of Rachel firmly in the territory of Judah in between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. But certainty eludes us …

Unlike the Tomb of the Patriarchs at Hebron, see previous post, I could never make a reconstruction drawing of Rachel’s Tomb. It was marked originally merely by a pillar and its subsequent forms simply reflected the architectural style of whoever was ruling the country. No one knows exactly where Rachel was buried, but the Biblical pointers indicate that it must have been somewhere close to the site traditionally believed to be that of the Jewish matriarch.

Leen,

Thank you for your research on this challenging issue. Porter’s explanation is certainly a creative way of handling the problem. I’ve written up an explanation which is a bit more traditional in having support from numerous scholars in the last hundred years. I will post that later today at http://blog.bibleplaces.com. I want to suggest here a few potential weaknesses in this proposed solution:

The texts locate Migdal Eder in relation to Jerusalem, not to Bethlehem. As far as I can tell, in the Sheqalim text, Migdal Eder could be any direction from Jerusalem, not near Bethlehem as you write. Micah 4:8 clearly places it near Jerusalem, not Bethlehem. In that case, Rachel’s tomb cannot be at the traditional location, because Rachel was buried north of Migdal Eder.

There is no evidence that tribal borders moved. As you say, Kiriath-jearim was located on the Judah-Benjamin border. Jerusalem was also on the north side of the border. That the borders would have expanded significantly at Judah’s expense in the period before Saul became king seems unlikely given Benjamin’s weakness and major population decrease (Judg 20-21). In any case, the shift proposed here is 5 miles, an enormous alteration for which we would expect to see some other evidence. The only evidence for it is the location of Rachel’s tomb, and I think there’s a much easier solution to handle this piece of data.

The first map does not correctly reflect the border description of Benjamin which runs through the Hinnom Valley *north to Mei Nephtoah* and west to Kiriath-jearim. The Mei Nephtoah point is very inconvenient for Porter’s theory, but it should not be ignored.

Thanks again for this post and your insights. As always, I benefit from your wisdom and experience.

—–I’m not sure what happened to my comment before, so I’ll try again.

Leen,

Thank you for your research on this challenging issue. Porter’s explanation is certainly a creative way of handling the problem. I’ve written up an explanation which is a bit more traditional in having support from numerous scholars in the last hundred years. I will post that later today at http://blog.bibleplaces.com. I want to suggest here a few potential weaknesses in this proposed solution:

The texts locate Migdal Eder in relation to Jerusalem, not to Bethlehem. As far as I can tell, in the Sheqalim text, Migdal Eder could be any direction from Jerusalem, not near Bethlehem as you write. Micah 4:8 clearly places it near Jerusalem, not Bethlehem. In that case, Rachel’s tomb cannot be at the traditional location, because Rachel was buried north of Migdal Eder.

There is no evidence that tribal borders moved. As you say, Kiriath-jearim was located on the Judah-Benjamin border. Jerusalem was also on the north side of the border. That the borders would have expanded significantly at Judah’s expense in the period *before Saul became king* seems unlikely given Benjamin’s weakness and major population decrease (Judg 20-21). In any case, the shift proposed here is 5 miles, an enormous alteration for which we would expect to see some other evidence. The only evidence for it is the location of Rachel’s tomb, and I think there’s a much easier solution to handle this piece of data.

The first map does not correctly reflect the border description of Benjamin which runs through the Hinnom Valley *north to Mei Nephtoah* and west to Kiriath-jearim. The Mei Nephtoah point is very inconvenient for Porter’s theory, but it should not be ignored.

Thanks again for this post and your insights. As always, I benefit from your wisdom and experience.

The borders that are described in Joshua 15 and 18 are very specific, using existing landmarks that are fixed (valleys, mountains, rivers, wells etc.). Kirjath-jearim and Jerusalem were simply occupied by both Judah and Benjamin. Joshua 18:14, when describing the borders of the children of Benjamin, calls Kirjath-jearim “a city of the children of Judah.”

I enjoyed this study and one surprise revealation was that the landmarks, used to describe the borders, are listed in perfect reverse order from chapter 15 to chapter 18!

Joshua 15:7-9 The going up to Adummim – Enshemesh – EnRogel – The Jebusite – The valley of Hinnom – The valley of the giants – The water of Nephtoah – Kirjath-jearim

Joshua 18:15-17 Kirjath-jearim – The well of Nephtoah – The valley of the giants – The valley of Hinnom – Jebusi – EnRogel – Enshemesh – The going up of Adummim

Todd, I don’t know what happened with your comment either, so I have pasted it in here:

Leen,

Thank you for your research on this challenging issue. Porter’s explanation is certainly a creative way of handling the problem. I’ve written up an explanation which is a bit more traditional in having support from numerous scholars in the last hundred years. I will post that later today at http://blog.bibleplaces.com. I want to suggest here a few potential weaknesses in this proposed solution:

The texts locate Migdal Eder in relation to Jerusalem, not to Bethlehem. As far as I can tell, in the Sheqalim text, Migdal Eder could be any direction from Jerusalem, not near Bethlehem as you write. Micah 4:8 clearly places it near Jerusalem, not Bethlehem. In that case, Rachel’s tomb cannot be at the traditional location, because Rachel was buried north of Migdal Eder.

There is no evidence that tribal borders moved. As you say, Kiriath-jearim was located on the Judah-Benjamin border. Jerusalem was also on the north side of the border. That the borders would have expanded significantly at Judah’s expense in the period *before Saul became king* seems unlikely given Benjamin’s weakness and major population decrease (Judg 20-21). In any case, the shift proposed here is 5 miles, an enormous alteration for which we would expect to see some other evidence. The only evidence for it is the location of Rachel’s tomb, and I think there’s a much easier solution to handle this piece of data.

The first map does not correctly reflect the border description of Benjamin which runs through the Hinnom Valley *north to Mei Nephtoah* and west to Kiriath-jearim. The Mei Nephtoah point is very inconvenient for Porter’s theory, but it should not be ignored.

Thanks again for this post and your insights. As always, I benefit from your wisdom and experience.

Todd, I don’t know what happened with your comment either. I tried to paste it in, but that didn’t go either! I have pasted it in a reply to myself to see if that works:

Leen,

Thank you for your research on this challenging issue. Porter’s explanation is certainly a creative way of handling the problem. I’ve written up an explanation which is a bit more traditional in having support from numerous scholars in the last hundred years. I will post that later today at http://blog.bibleplaces.com. I want to suggest here a few potential weaknesses in this proposed solution:

The texts locate Migdal Eder in relation to Jerusalem, not to Bethlehem. As far as I can tell, in the Sheqalim text, Migdal Eder could be any direction from Jerusalem, not near Bethlehem as you write. Micah 4:8 clearly places it near Jerusalem, not Bethlehem. In that case, Rachel’s tomb cannot be at the traditional location, because Rachel was buried north of Migdal Eder.

There is no evidence that tribal borders moved. As you say, Kiriath-jearim was located on the Judah-Benjamin border. Jerusalem was also on the north side of the border. That the borders would have expanded significantly at Judah’s expense in the period *before Saul became king* seems unlikely given Benjamin’s weakness and major population decrease (Judg 20-21). In any case, the shift proposed here is 5 miles, an enormous alteration for which we would expect to see some other evidence. The only evidence for it is the location of Rachel’s tomb, and I think there’s a much easier solution to handle this piece of data.

The first map does not correctly reflect the border description of Benjamin which runs through the Hinnom Valley *north to Mei Nephtoah* and west to Kiriath-jearim. The Mei Nephtoah point is very inconvenient for Porter’s theory, but it should not be ignored.

Thanks again for this post and your insights. As always, I benefit from your wisdom and experience.

oldest photo here!

http://jnul.huji.ac.il/dl/maps/jer/images/jer084/Jer084_b.jpg

Very interesting, but couldn’t call it a photo …

Discovered this thread today – sorry for my late post.

In the late 80s and early 90s I did some (mainly tradition-historical) research on Rachels tomb and suggested that it could have wandered from the north (Qubur bene Israin) to the later known site near Bethlehem. The Judean tradition could have adopted the Benjaminite tradition of “Mother Rachel” as an additional legitimation for the Southern claim to power.

You can find the bibliographical information about my article here: http://aleph.nli.org.il/F?func=find-b&request=000060401&find_code=SYS&local_base=RMB01

from what angle would you say is this painting from

http://www.zadikim.org/kever_rochel.html#

I would say from the northeast.

what is this small arch?

http://www.forum.ladaat.info/download/file.php?id=5279

thanks

Eli,

The arch appears to be a doorway that leads into a small structure that is built against the main building. I don’t know it function, but it looks like an entrance to either a cistern or storeroom.

The prophet Samuel met Shaul in Ramah and directed him to return home. On his way he was going to meet 2 people in Zelzah. Surely, Shaul’s movement was therefore to head North from Ramah, therefore should we not seek Zelzah somewhat North of Ramah?