I believe that Scripture and archaeology show that the place in Bethlehem where Jesus was born was not a random cave or grotto, but a different location that was prepared centuries earlier for this purpose.

According to Luke 2.1-5, Bethlehem is the place where Joseph went for the Roman census. Both Joseph and Mary were descendants of the family of King David. When the Roman Governor Quirinius ordered a census to be carried out, Mary and Joseph had to travel to their ancestral home in Bethlehem. It must have been an uncomfortable journey when Mary was almost 9 months pregnant and had to travel, probably on the back of a donkey, from Nazareth to Bethlehem – a 100-mile-long journey through the Jordan Valley!

On arriving in Bethlehem, Joseph couldn’t find a place to stay. We are told that there was “no room in the inn”. The only available place for the Son of God to be born was a stable, which had to be shared with animals. How do we know that it was a stable? In Luke 2:12, an angel told the shepherds that a Savior was born and that they would find him as a babe lying in a manger. Mangers are feeding troughs for animals, usually found in stables.

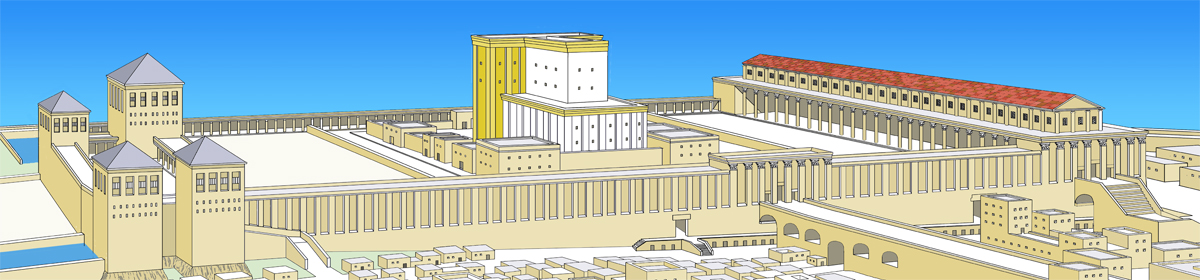

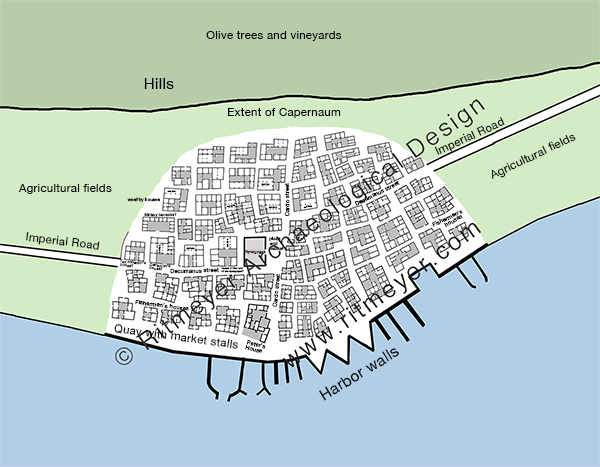

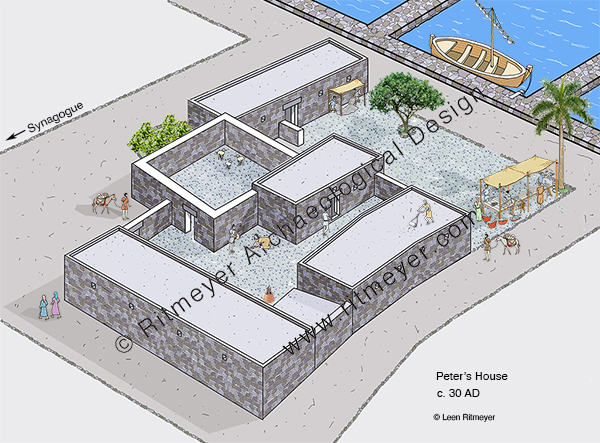

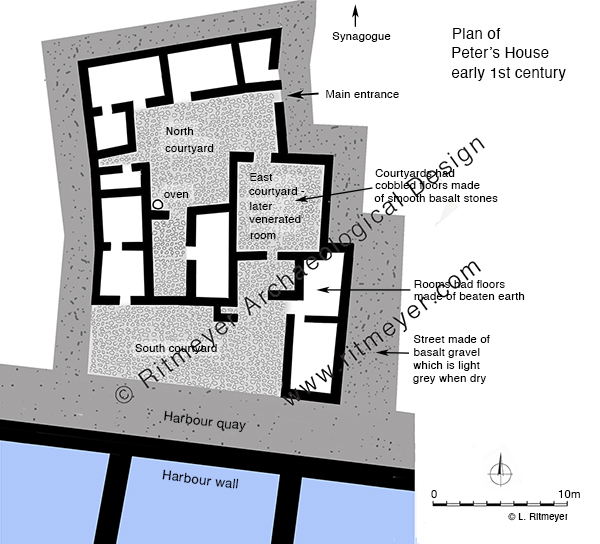

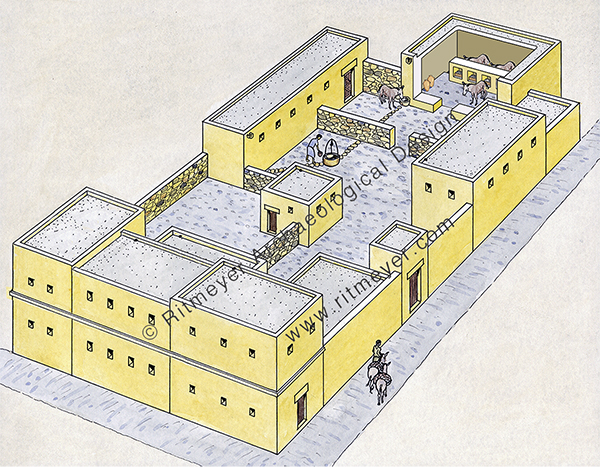

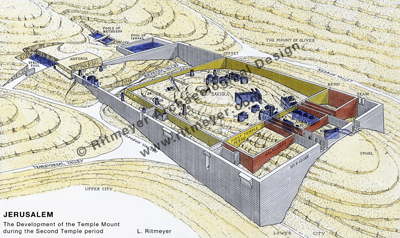

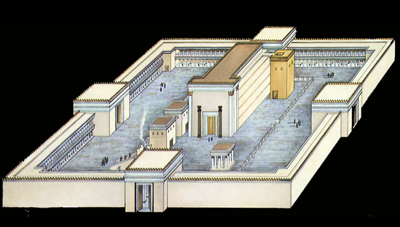

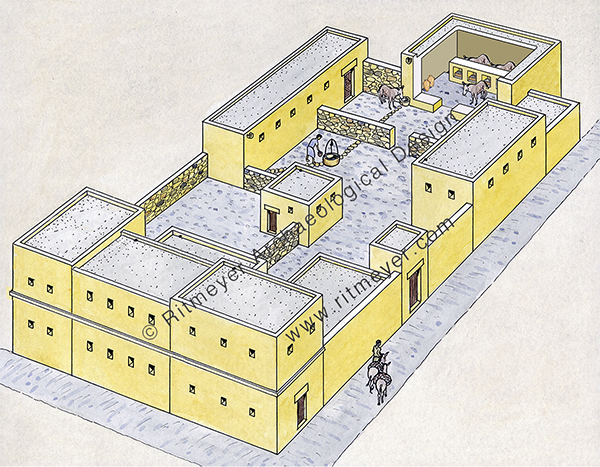

Why was there was no room in the inn? The NT Greek word for “inn” is kataluma, which has been translated “guest room” in Mark 14:14 and Luke 22:11. In the story of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10:34, the Greek word for ‘inn’ is pandokion. This was a proper inn or caravanserai as it had an innkeeper which is called a pandokus. There is no mention of an innkeeper in the ancestral home of Mary and Joseph. Inns were large buildings, often with two stories of rooms built around a courtyard. The upper rooms were used by the travelers, while the animals would be kept in stalls or stables.

Large dwellings, such as the ancestral home of Mary and Joseph would have looked similar, i.e. two story high rooms built round a courtyard. As members of Joseph and Mary’s extended family had apparently arrived earlier and occupied the guest rooms, Joseph and Mary had to stay in the stable block of the same ancestral home.

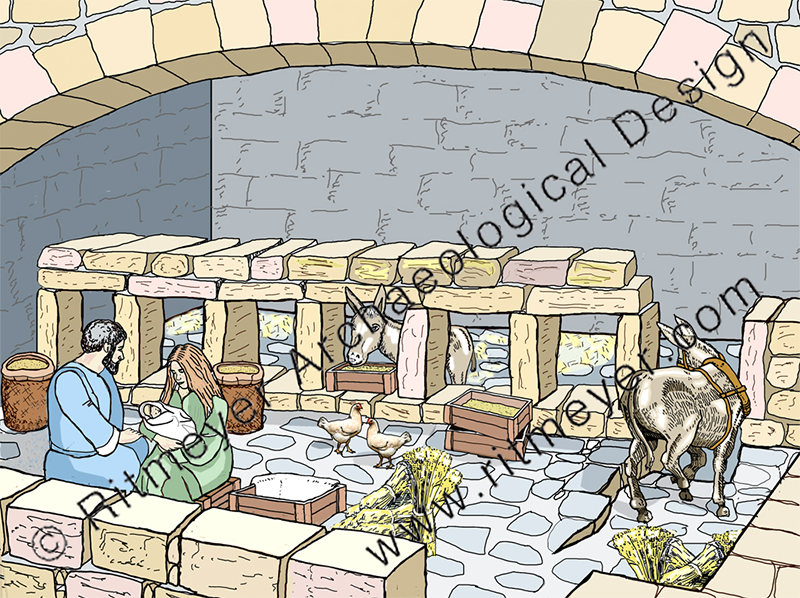

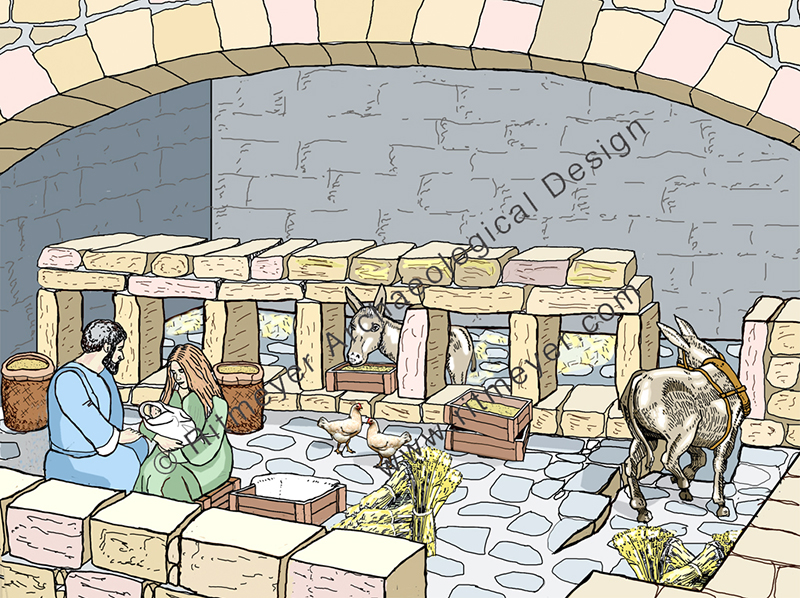

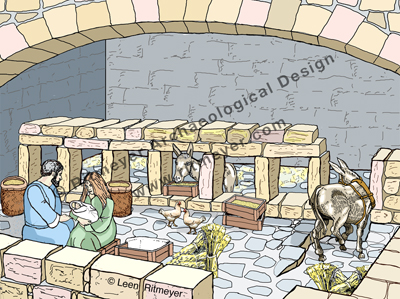

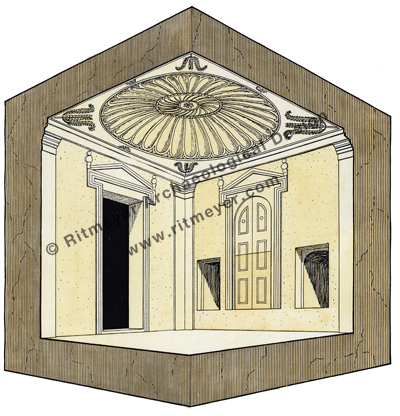

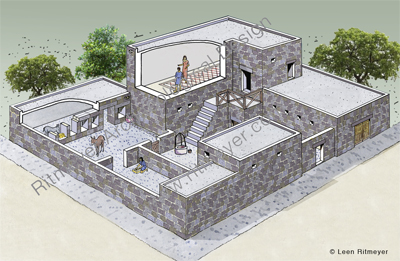

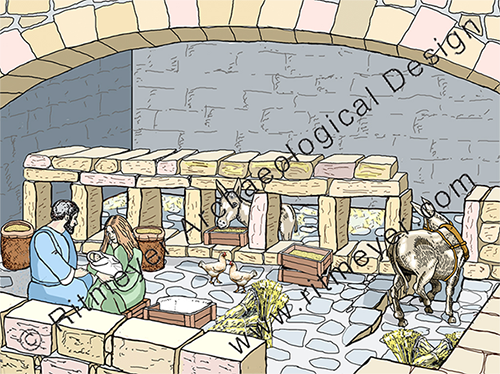

So, what did a stable look like in the time of Christ? From archaeology we know that stables looked like rooms with a fenestrated wall, i.e. an interior wall with several low windows. Animals were placed behind this wall, and sacks of provender were stored in the first half of the room. At feeding time, the fodder was put in wooden boxes or baskets and placed in these windows.

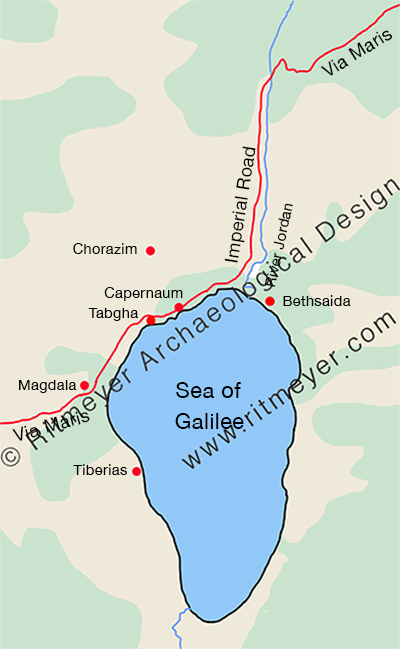

It was probably in the storage part of the stable block that Mary and Joseph had to stay and where Jesus was born and the babe was placed in a wooden box. Stables with fenestrated walls have been found in many places, such as Capernaum and Chorazin that are illustrated here, and in later monasteries.

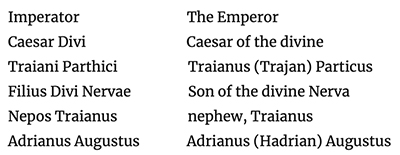

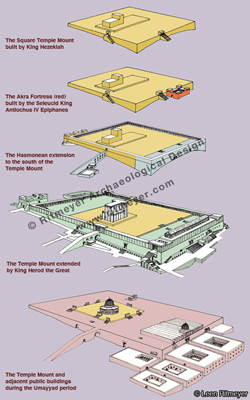

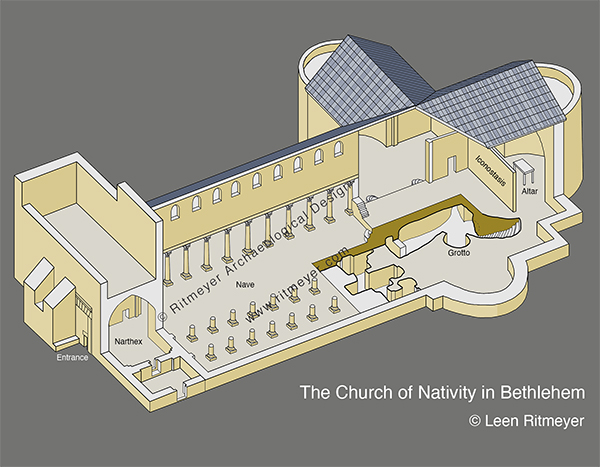

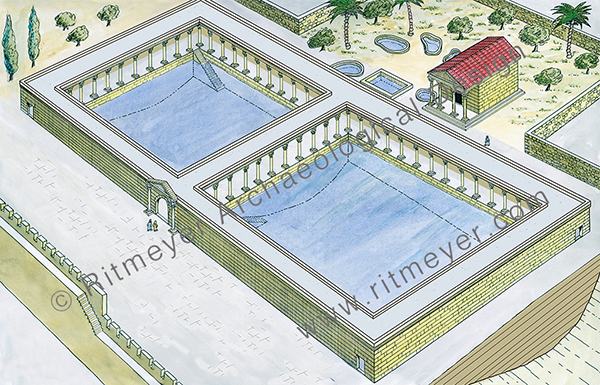

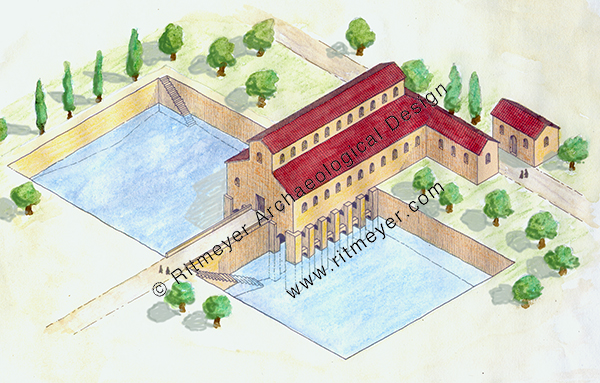

So, where did the tradition that Jesus was born in a cave originate from? Here is a suggestion. After 135 AD, a Roman garrison occupied Bethlehem as indicated by Roman inscriptions that were found near Rachel’s Tomb. In the first and second centuries AD, the Romans venerated Asclepius as the most important god of healing. Many temples and shrines were built to celebrate his healing powers. The Roman soldiers may have built a shrine to Asclepius in a cave near Bethlehem. “It is possible that such a military presence would have led to the establishment of an Adonis cult in the same way as the Roman military presence in Aelia [Capitolina] led to an Asclepius/Serapis cult in the caves adjacent to the Pool of Bethesda.” [1]

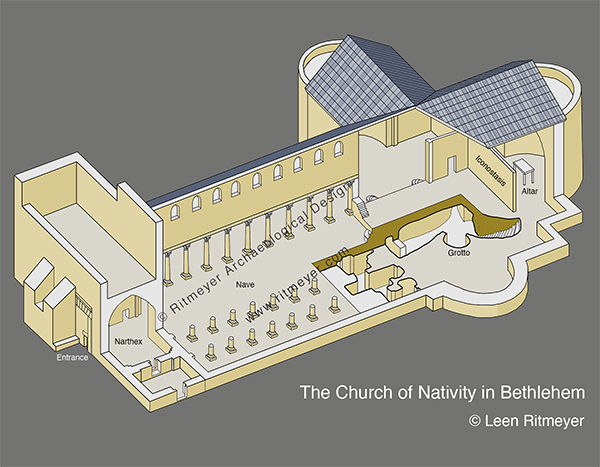

In the fouth century, Constantine the Great tried to eradicate paganism and replace it with Christianity. The building of the Church of the Nativity over this cave may have been part of this program. Similarly, a church was built over the Pools of Bethesda.

In a previous post I asked the question what is the importance of Bethlehem and which inn/hostel was chosen by God as the place for His son to be born in?

To prepare for the conquest of Jericho, Joshua sent out two spies that stayed overnight with Rahab. She was a harlot (zonah), yet living with her family, which is unusual. In Hebrew, the word zonah is closely related to mazon which means food, and lehazin which is to feed. It has been suggested that she ran an inn, where the two spies would naturally have gone for shelter. She also may have provided “extra services” as part of running the hostel. It possibly was a Canaanite custom, which was well accepted among those nations, who didn’t have the rule of God to guide their society. Because of her faith, Rahab was the only person, with her family, that was saved.

Rahab married Salmon and their son was called Boaz, who must have settled in Bethlehem when Judah captured its inheritance. Boaz married Ruth in Bethlehem and she became the great-grandmother of David (Ruth 4.10). Gentile Ruth was, of course, one of these amazing few women mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus in Matthew 1:5. King David was born in Bethlehem and anointed king there by Samuel the Prophet.

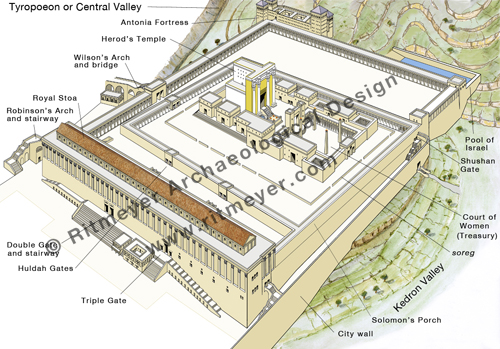

Near the end of his life, David had to flee from his son Absalom, when he rebelled against him. He stayed with the aged Barzilai the Gileadite, whose son Chimham returned with David to Jerusalem (2 Sam. 19.37-40). To provide him with a source of income, it appears that David may have given him part of his own inheritance in Bethlehem to build an inn (mentioned in the early Jewish source, Targum Yerushalmi, Jer. 41.17a), and called “Geruth Chimham”, “Habitation of Chimham” (Jer. 41.17). The building of inns/hostels may have been a family tradition! As small towns like Bethlehem usually had only one inn, it is reasonable to suggest that Jesus may have been born in this inn. As the guest chambers were full, Jesus would have been born in the stable block that was part of the same inn. It would be amazing to contemplate that through the generosity of David to Barzilai and his son Chimham, a birthplace for Jesus was prepared about 1000 years before his birth!

[1] Henri Cazelles (1992), “Bethlehem”, in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, Vol 1, 712-714.