Fifty years ago today, I embarked on a career which previously I hadn’t know existed and couldn’t have dreamed up for myself. It combined the disciplines of archaeology, ancient architecture, history, education, and Biblical Studies. Since realising, a few years later, that this would require the wearing of multiple hats, (although my fedora was the one that was most practical and the one that became identified with me), I got used to various titles like: “Archaeological Architect”,“Conservator” and “Lecturer”. However, I soon learnt that the hat of Bible Student was the most valuable, and that which could encompass most of my interests. My studies of the Bible had taught me core skills that could be useful in many situations. Research, analysis, interpretation, and application, to mention but a few, all could be improved and enhanced by immersion in the Good Book.

A few months ago, one of my sons, Ben, was looking at a book that contained drawings of cities from Biblical times with one of his sons, Seth ( my now 5-year-old grandson). Ben mentioned that some of these sites were thousands of years old. Seth exclaimed: “as old as Grandad!” Now, I do not claim to be thousands of years old.

But when I looked around my workroom/studio in the cottage we now live in South Wales, I realised that within its walls lie physical evidence of 50 years of visualising the Bible. Its main holding is a substantial library of volumes that contains many of my reconstruction drawings. Some of the most well-known are Study Bibles and our own books, most of which have been published by Carta of Jerusalem. There are traditional dig reports and guide books too. And, added later, also items of a more unusual shape, like CDs and DVDs.

So – if this turning of the year makes you feel like hearing the story of Ritmeyer Archaeological Design, gather round and I will try my best to tell it. And for those of you who on occasion have asked: “How can we learn to do what you do?”, you may pick up some hints or feel that you have had your fill already.

A Dutchman, I graduated in 1967 with a degree in Physical Education from Arnhem. At that time there was compulsory military service, and within a week all my friends had been enlisted, but I was the only one not called up. As I could not commit myself to at least one year of teaching, I decided to go and travel until the military call-up arrived.

After the Six-Day War, there was a shortage of manpower in Israel, as most men were still mobilised. So, I volunteered in Kibbutz Yad Mordechai near the Gaza Strip and stayed there for almost half a year. I used my free time to travel through the Land, began to read the Bible and learnt Biblical Hebrew. The combination of knowing the geography of the Land and learning Hebrew greatly increased my understanding of the Scriptures and developed in me a love for the Land that only got stronger over time and never left me.

In 1969, I decided to try and settle in Israel, which as a non-Jew was not easy, but I eventually found work on the Temple Mount Excavations under the direction of the late Prof. Benjamin Mazar (1906-1995). Before finding this position, I had written a letter to David Ben-Gurion, the former Prime Minister of Israel and was granted permission to stay as a temporary resident. I held this status in fact, for twenty years – a permanent temporary resident!

And reflecting on the way I had originally found the job on the Temple Mount Excavations, it also seemed pretty fortuitous. In 1972, I had read a report about the Temple Mount Excavations in which they appealed for more staff. My late sister Martha had got a job illustrating ancient architectural elements when she applied. She did very well at this work, which she liked very much. We decided to move from the area of Petach Tiqva (Door of Hope), the area where we had been living and earning a livelihood, and we found a house in Bethany near Jerusalem.

After hearing from Martha that I was also looking for work, the deputy director of the dig, Meir Ben-Dov, asked me to come and work there too. I was not too enamoured when I saw the dig with its broken stones and walls and volunteers slaving away in the dust and heat. He offered me the job of drawing potsherds in a tiny room that was a converted cupboard. I ran away as fast as I could! However, he persisted and eventually offered me the job of surveyor. I had never done anything like that but replied that I knew where the zero on the tape measure was and was ready to give it a go.

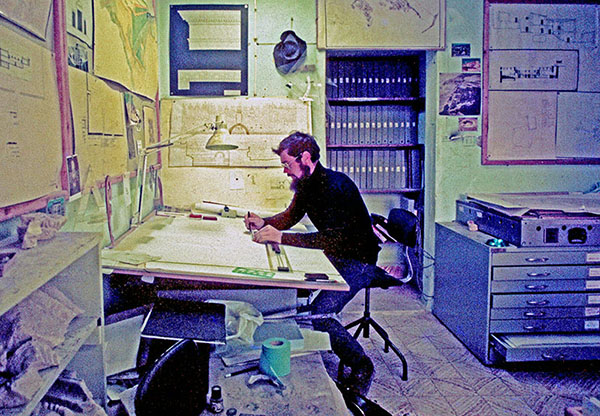

So, on the 1st of January 1973 I started to work as the dig’s surveyor, making plans on a scale of 1:50. An Irish architect, Brian Lalor, later to achieve renown in his own country in the field of printmaking, trained me in and I liked the work. When I showed him my drawings, I observed what he did with them. He reduced my plans and then completed broken or missing walls and reconstructed elevations and then made complete reconstruction drawings of the building remains that I had surveyed. I thought this was fantastic and, seeing that I was interested, Brian gave me a Byzantine bath house to reconstruct, a work that quickly drew me in.

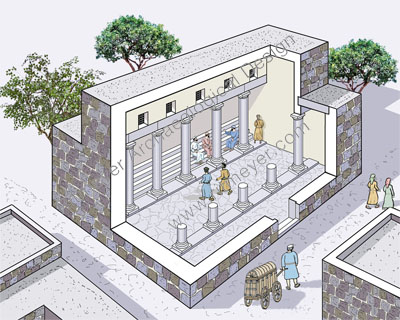

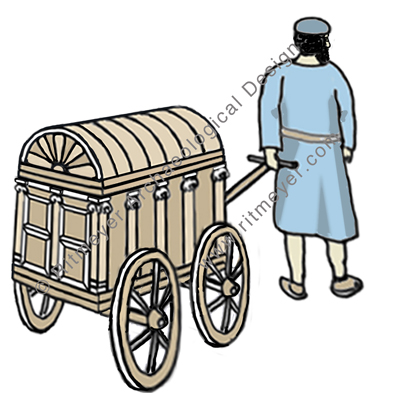

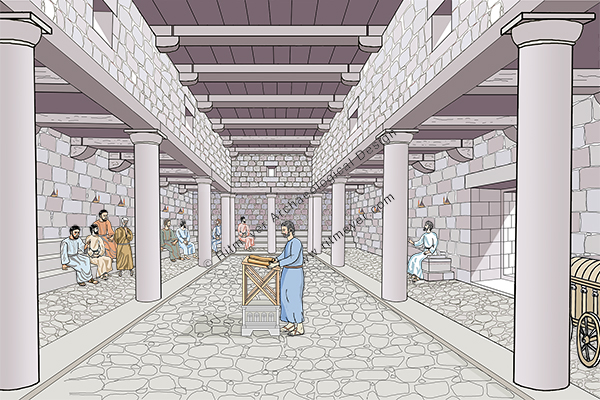

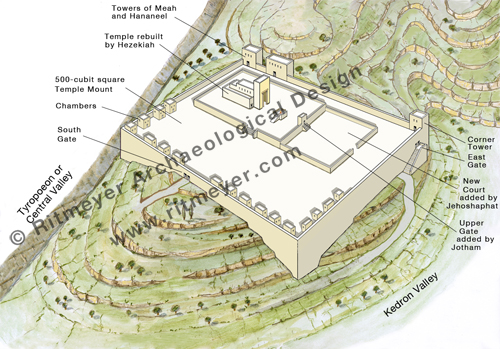

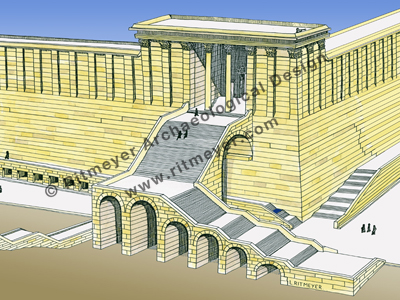

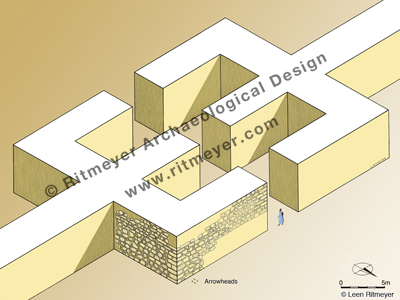

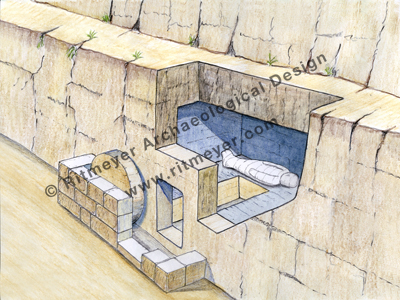

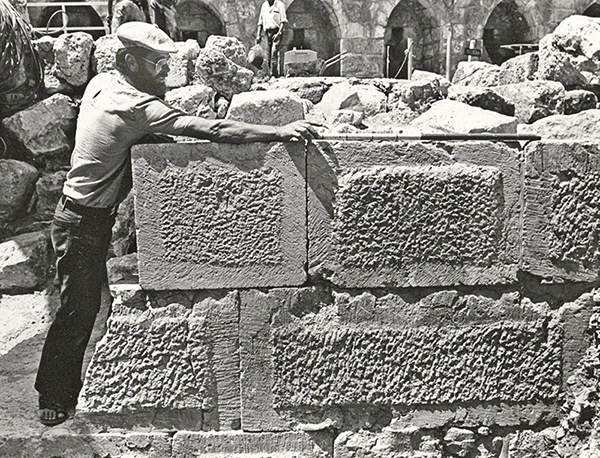

The great joy in archaeological excavations is figuring out how architectural structures worked. A couple of months later I was asked to survey the Herodian shops to the east of the Triple Gate. These shops were at a much lower level than the street in front of this gate. It was obvious to me that the roof of these shops must have supported the street above. I asked Brian what kind of roofs they might have been, but the response was unclear. One morning, when the sun was shining at just the right angle, I looked up and saw the burnt imprints of arches in the Southern Wall of the Temple Mount and figured out that the descending stepped street above must have been built over the vaulted ceilings of these shops. The shops had been burnt down by the Romans in 70AD, but before the vaults collapsed, the fire burnt into the Temple Mount wall, leaving the imprints of the vaults as an evocative testimony to this dreadful inferno!

My theory at first was greeted with unbelief, but when Prof. Mazar and Brian came to have a look, they were bowled over when they saw the actual evidence. The difference in height between these vaults was 60 cm (2 feet). This corresponded to the height of three steps. And so, it was possible to make a watertight reconstruction of the street above the shops. The excitement and thrill of this discovery got me hooked on ancient architecture for life.

Four months later, Brian left to return to Ireland, and Benjamin Mazar told me to sit in the architect’s chair and to continue supervising a small team of volunteer surveyors that I had trained in. I was left in charge of the architect’s office, and that is how my career as an archaeological architect took off. During the winter months of 1973, Mazar sent me to the library of the Rockefeller Museum to study ancient architecture under his personal guidance.

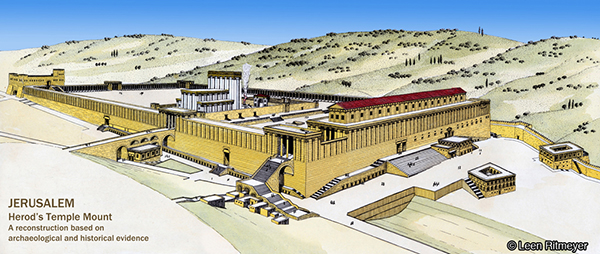

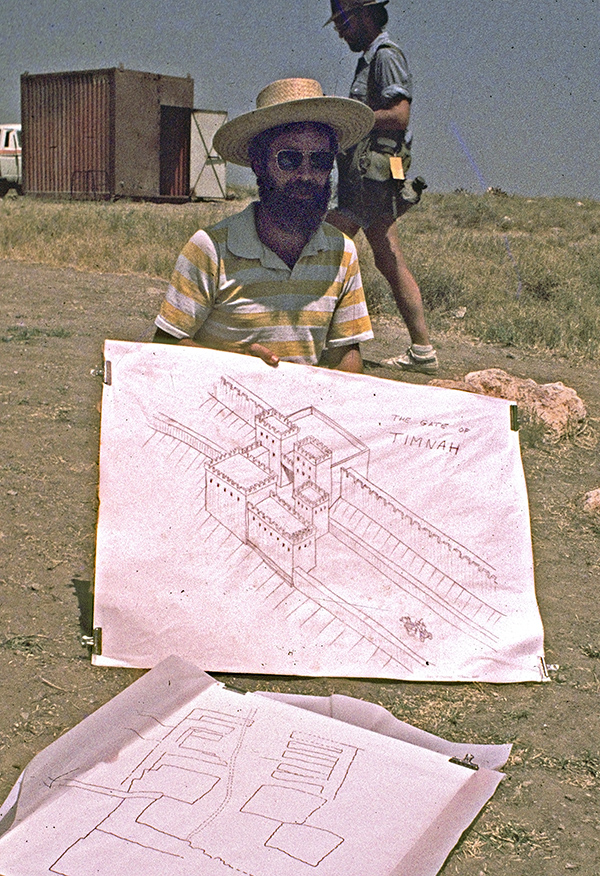

The making of reconstruction drawings, that became my speciality, was born out of necessity. Apart from my regular architectural work, some staff members including myself, gave tours to other archaeologists and visitors. It was this experience that convinced me of the necessity for these drawings. One of the first stops on the tour was Robinson’s Arch, one of the four gates in the Western Wall of the Herodian Temple Mount. I tried to explain the features of the arched staircase that led up to the Temple Mount from the street below, sometimes using my hands and feet. From questions I received afterward, I realized that not everybody could visualize how it worked. I then made my first reconstruction drawing of Robinson’s Arch. On this drawing, I indicated in color the visible remains and drew the reconstruction in black and white lines. This visual connection with the archaeological remains made the reconstruction immediately recognizable. Seeing people’s faces change from incomprehension to clear understanding assured me that this was the way to go.

Eventually, my reconstruction drawing of the Temple Mount that was used by many guides, became a classic and has been published in many books.

During the Yom Kippur war in October 1973, Israel captured large areas of Syria from Kuneitra to halfway down to Damascus. This area was referred to as the Bashan. After the fighting was over, the soldiers who were archaeologists went back to their normal Unit for the Knowledge of the Country. They had to do an archaeological survey of the Bashan and found two-story Roman houses that had recently been lived in still standing up.

As the archaeologists couldn’t make architectural plans, I was employed by the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) to join this unit. This was very exciting, as this was my first visit to Syria and I got to know all the up-and-coming young archaeologists, such as Amihai Mazar, Dan Urman, Zvi Ilan and Amos Kloner.

Later, some of this group asked me to make drawings for them. Amihai employed me to draw up the plans of the Tel Qasile excavations and later asked me to join the Tel Batash (Timnah of the Philistines) dig, Dan Urman asked me to join the Tel Nitzana excavations and draw up the plans of Rafid on the Golan, Zvi Ilan asked me to make a reconstruction drawing of the Byzantine Synagogue that he had excavated in Meroth, and for Amos Kloner I drew up some of the caves of Bet Guvrin.

Back at the Temple Mount excavations, I finalised the survey plans, and made reconstruction and publication drawings of buildings belonging to different periods. Prof. Benjamin Mazar was interested in the Herodian and earlier periods, while Meir Ben Dov was given responsibility for the later periods. From my office room I could see who was coming down the steps to see me. When Mazar came down, I quickly put the Herodian drawings on my desk and exchanged them for later period drawings when Ben Dov was visiting!

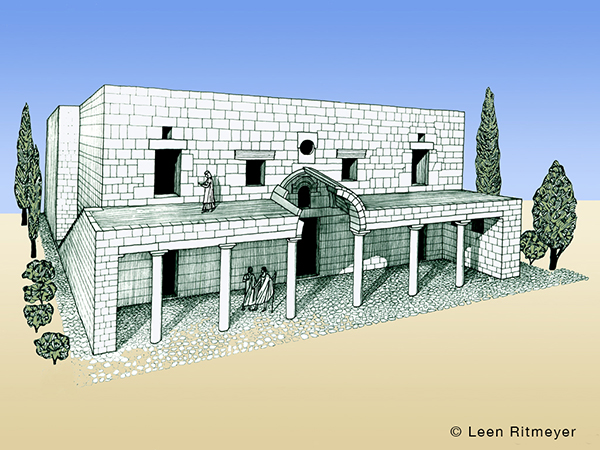

Another chapter in my career opened when I was asked to reconstruct the Crusader Church of Saint Mary of the Germans in Jerusalem. This work involved the building of a staircase and the pillars that once supported the vaults of the hospital hall of the hospice complex in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. To make the pointed arches, I cut templates out of carton for the individual arch stones on the flat roof of our house in Melchizedek Street and gave those to masons in Bethlehem who cut the stones and built the arches.

It was the first of several restoration projects I later became involved in, eg the Byzantine Cardo and the Herodian villas in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. Restoration consists of consolidating the actual remains to prevent deterioration. At times, it is important to reconstruct parts of the ancient ruins. This is extremely sensitive work. It is very important not to build up the site too much, but to do it so that one gets a real feeling for how it would have looked originally.

My life changed in 1975, when Kathleen, an Irish archaeologist, came to work on the Temple Mount Excavations. I still remember her joining the tour I was giving on the dig at the southwest corner, but had no idea that eventually she was to become my beloved wife. She was certainly the best find ever!

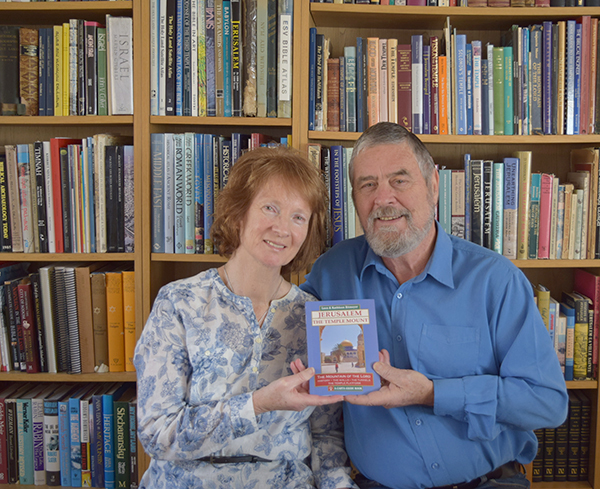

In 1983, Kathleen and I established a partnership called Ritmeyer Archaeological Design (RAD), which is an independent partnership devoted to archaeological reconstruction and the production of educational materials, and it is still active today. Kathleen’s excellent writing and research skills enabled us to produce books and varied educational materials that people still find useful today. Just as much as I like drawing lines on paper, she says that she loves to “push words around the page!” Working together has been a great blessing, as we have similar interests and complement each other.

Much of my time in Israel then involved the restoration, first of the Byzantine Cardo and the Herodian Quarter in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City, later called the Wohl Museum.

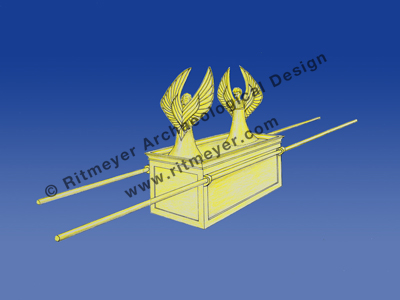

In 1989 we moved to England, and even though we no longer had a Jerusalem address, the projects kept coming in. One of the largest such projects was the design of models of the Tabernacle, Solomon’s Temple, and Herod’s Temple and Temple Mount for a Jewish philanthropist in Washington, DC. Photographs of these models, beautifully crafted by York Model Making, are included in RAD’s Image Library.

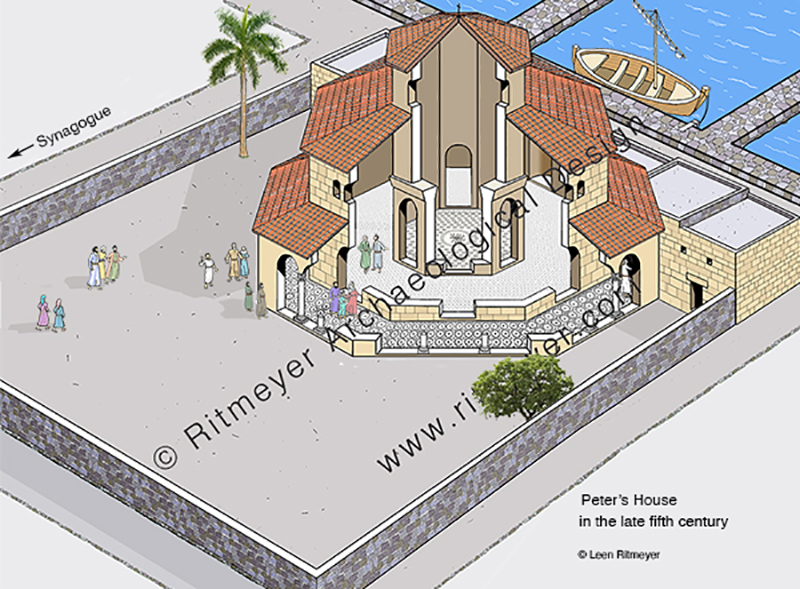

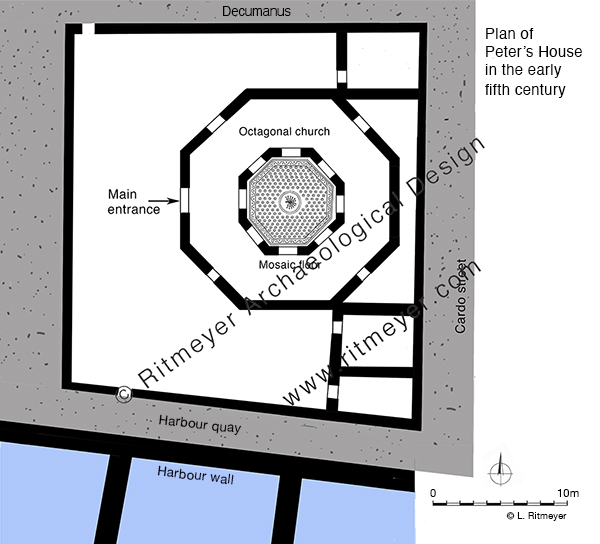

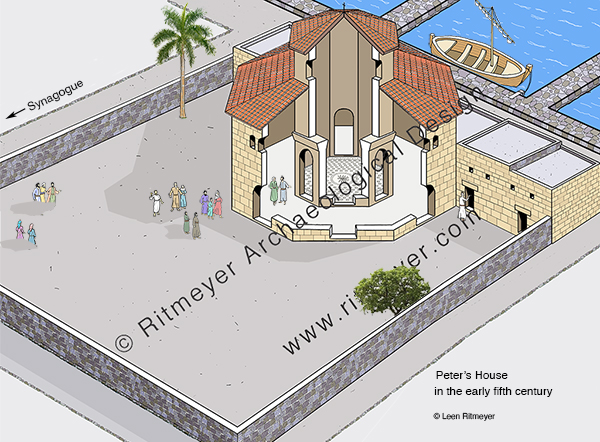

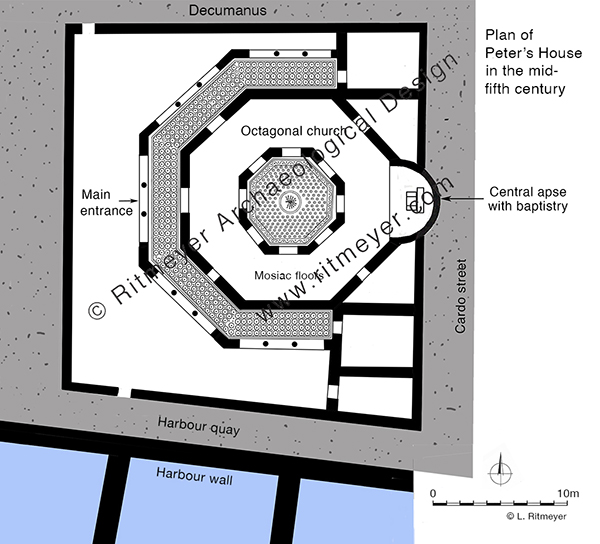

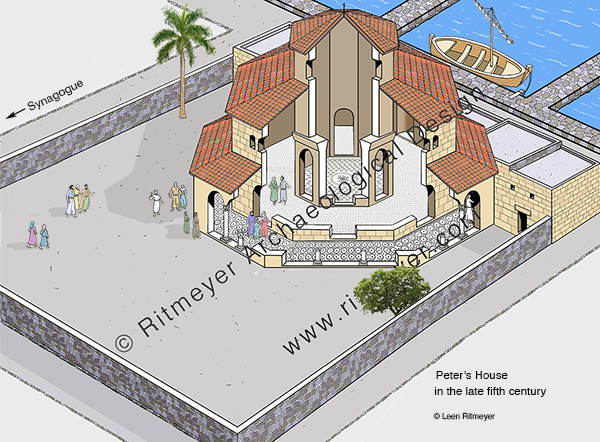

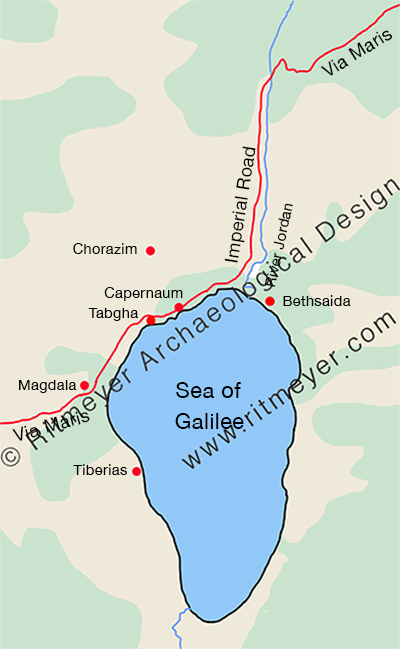

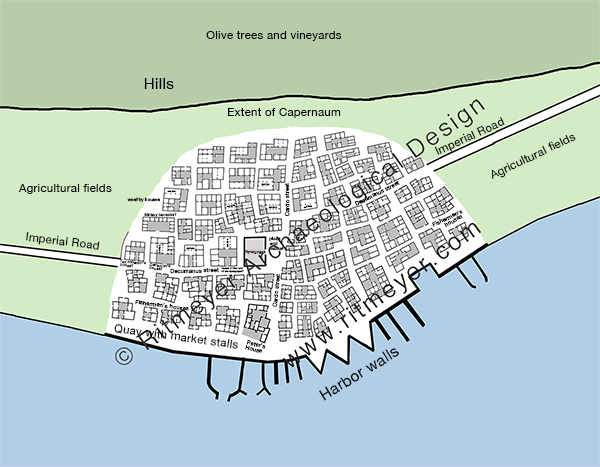

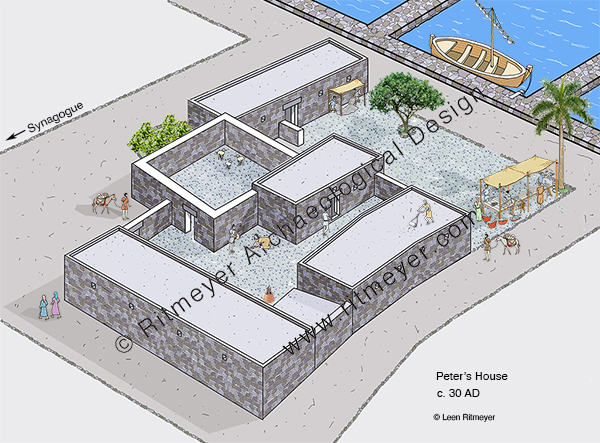

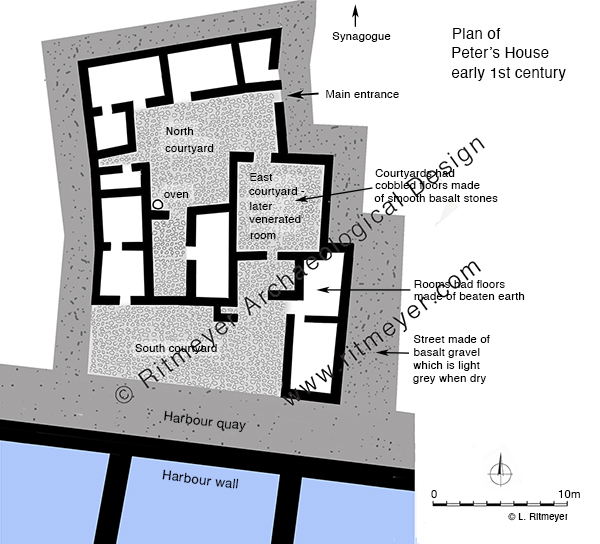

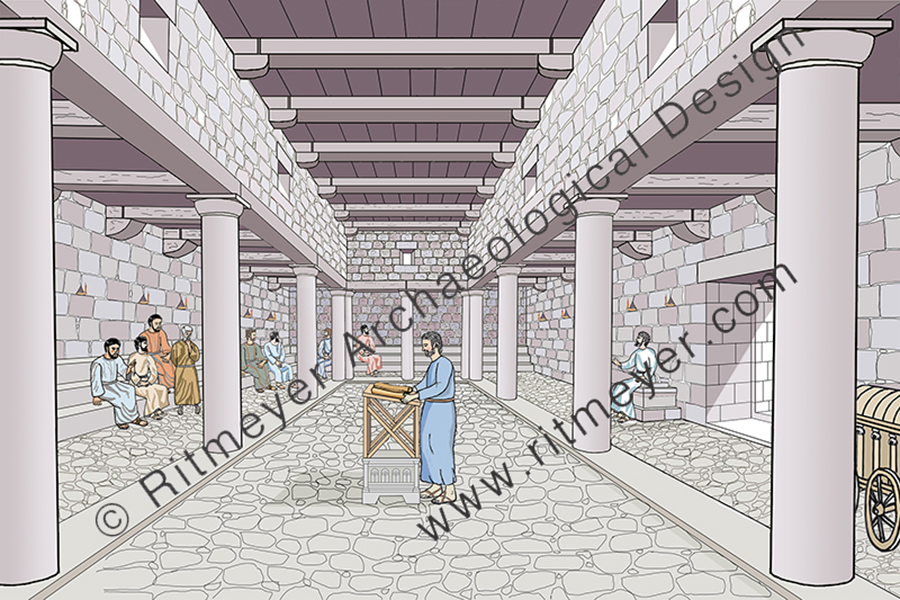

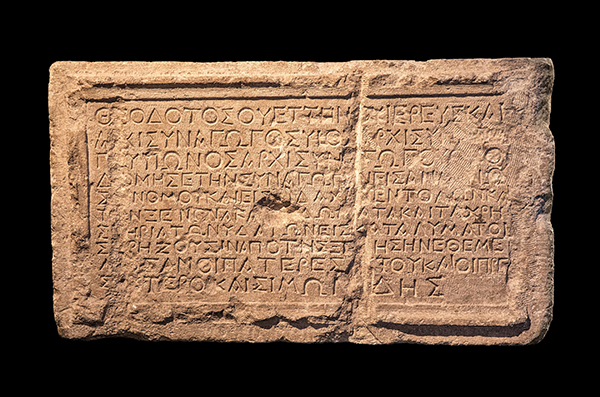

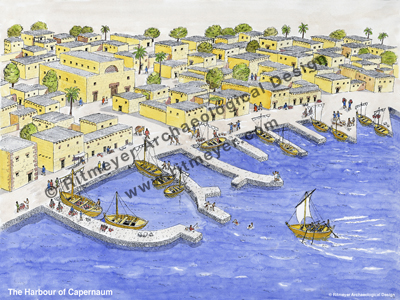

Other projects I’ve worked on in recent years, include mapping every journey in the Bible and illustrating as many as these mappable events as possible for the United Bible Societies’ Augmented Reality Bible. And even more recently, I’ve collaborated on a voice-driven VR experience, in which a VR headset allows one to walk through a city or large building in a specific period. The first project we worked on focused on Capernaum. I provided all the archaeological and historical background, whereas other artists made the relevant 3D-enabled drawings and computer experts developed the technology.

My work has also brought many rewards for our family life. When our children were young, I was often able to take them on digs and give them memorable experiences that they still talk about today. When they were older, they helped me at times with photography, cartography, and illustration.

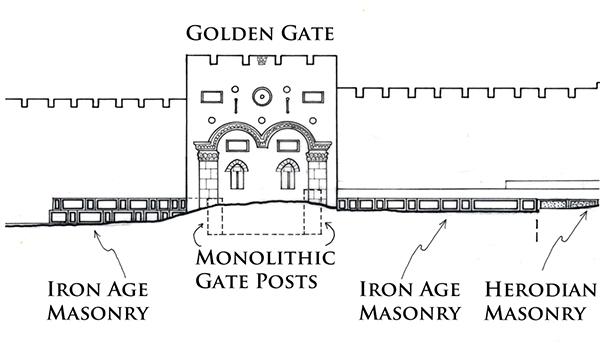

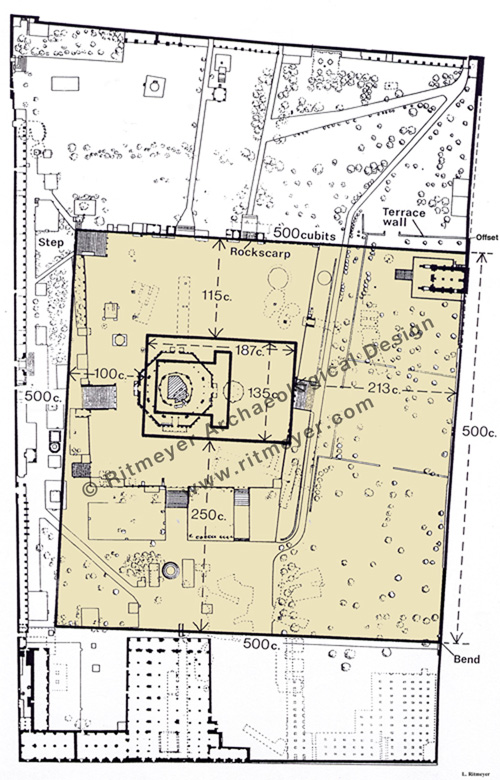

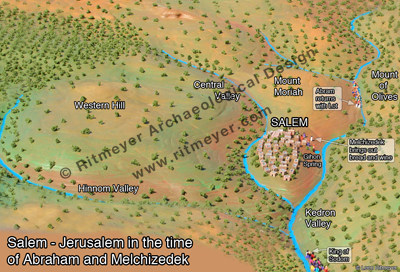

If you were to ask me what were some of the most exciting moments in my career, I would say they would be the making of major discoveries, such as the location of the Holy of Holies of Solomon’s Temple and the emplacement of the Ark of the Covenant, and the identification of the Middle Gate mentioned in Jeremiah 39:3. The latter made it possible to relive, as it were, the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. Arrowheads found among the charred timber and ashes at the base of the tower point to a fierce battle around the city walls of Jerusalem in the time of Zedekiah. Our hands got black with soot—tragic evidence of the fall of Jerusalem.

And for those brave ‘wannabes’ who would like to follow my footsteps, all I would say is: listen to your heart, find an encouraging mentor, and watch how he/she does things on a site you love in the Land. Make yourself as indispensable as possible and make reading the Word in the ruins your inspiration.