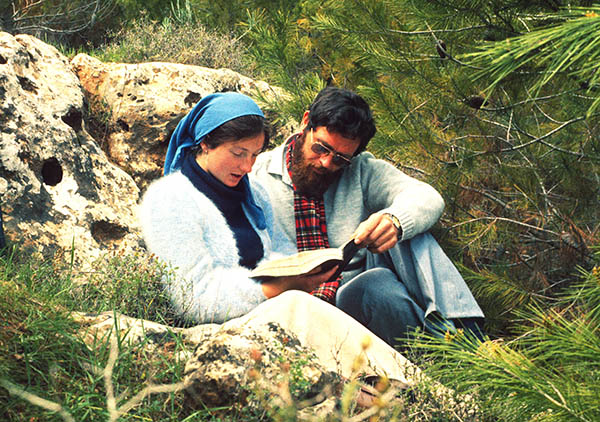

Today, the 1st of October 2023, Kathleen and I celebrate our 45th (sapphire) anniversary. We enjoyed many wonderful years of love, loyalty and dedication to each other, and shared interests in our faith, family, and archaeological work. We both love God’s Word, the Land of Israel and other biblical lands, and the Hebrew language. In many ways Kathleen (I call her Katia) is my equal and more, but she never wanted to attract attention to herself. All she ever wanted to do was to be my helpmeet. Katia was and always will be the “desire of my eyes”. Here is how it began.

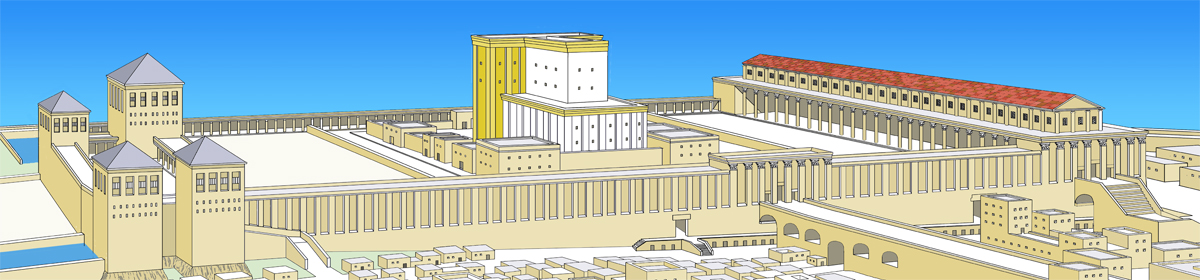

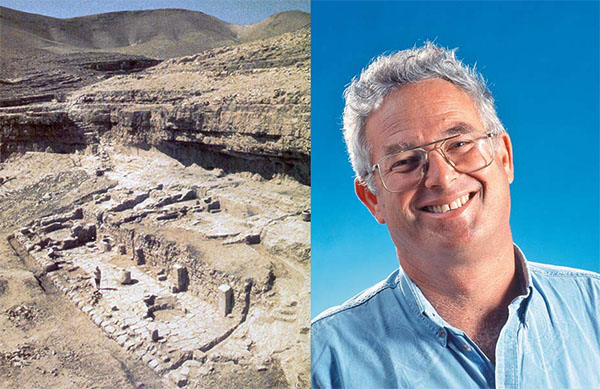

The 1st of October 1975 was exactly 48 years ago that Kathleen O’Mahony (BA Archaeology, University College Dublin, Ireland, PGCE) arrived at the southwest corner of the Temple Mount Excavations to join the introductory tour I was giving for new volunteers. Katia had come to work on the dig as archaeological supervisor and occasional surveyor.

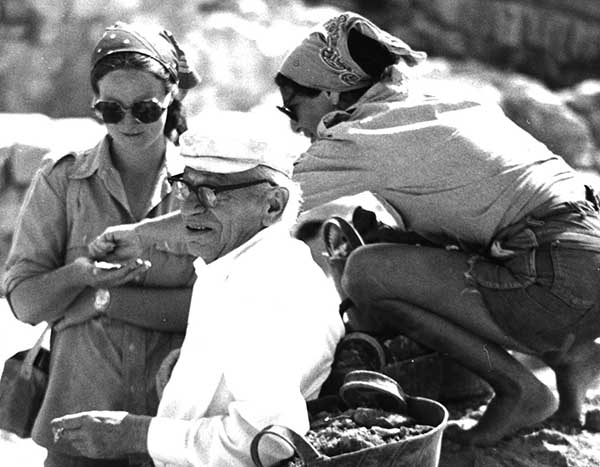

Katia at left with Prof. Benjamin Mazar, director of the Temple Mount Excavations, in the foreground, and an American volunteer at right.

Living in Jerusalem and seeing the variety of representatives of the different churches, she began wondering which of them was right. Katia also asked me what I believed, and so began many sessions of her asking questions and me answering from the Scriptures. We soon realised that our relationship was growing into something beyond teacher and student.

We also celebrate 40 years of our Ritmeyer Archaeological Design (RAD) partnership. Katia is a professional archaeologist and excellent researcher, and her outstanding writing skills enabled us to co-author many books. We both love bringing the past to life, she with words and I with reconstruction drawings. We often reminisce about the many projects we have been involved with.

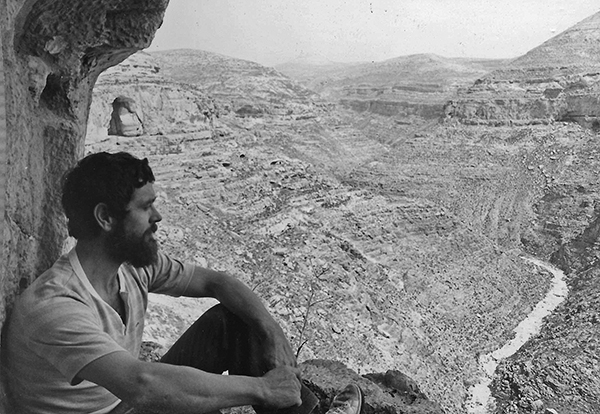

In the first year of our partnership, I joined the late Yizhar Hirschfeld in his search for Byzantine monasteries in the Judean Desert.

The Byzantine monastic movement in the Judean Desert was initiated in the 4th century AD by Chariton, who was born in Iconium (modern Konya, in Turkey). After the cessation of persecution of Christians, he made pilgrimage to Jerusalem, but was taken captive by bandits, who took him to a secret treasure cave in Pharan, near the spring of Ein Fara, not far from Anathoth (Arabic anata). Eventually he was rescued and inherited the cave and its contents and founded his first monastery there. I visited this monastery for the first time in 1970.

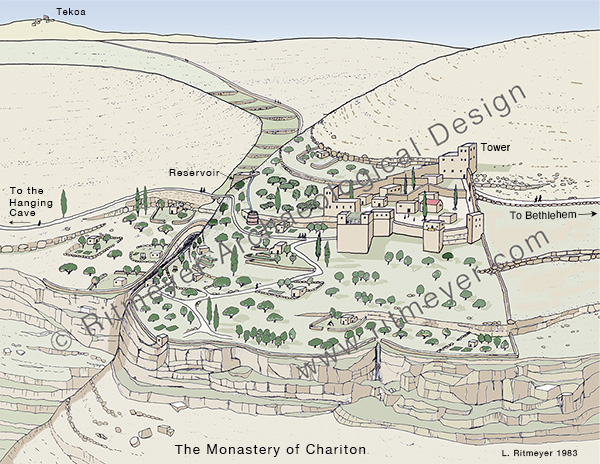

After leaving Pharan, Chariton established two other monasteries, the first one was the Laura of Douka, on the Mount of Temptation, and later the Monastery of Chariton – also called Souka, near Tekoa. The name of the monastery’s founder, Chariton, is preserved in the Arabic name of the site that is called Khirbet Khureitun and of the valley below, Nahal Khureitun. The modern name of the valley is Nahal Tekoa.

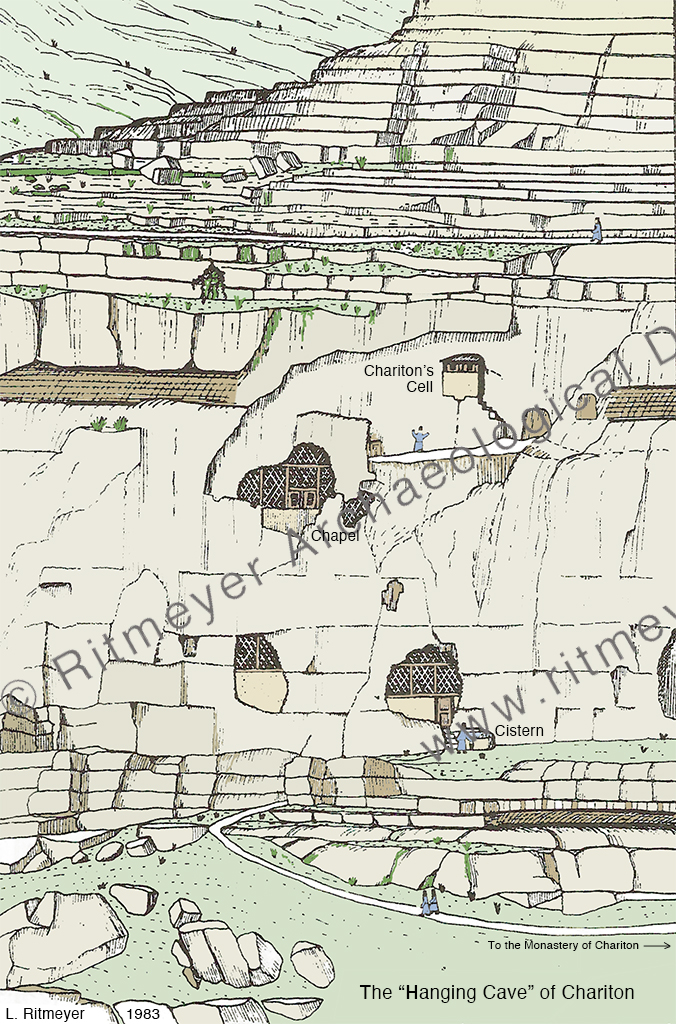

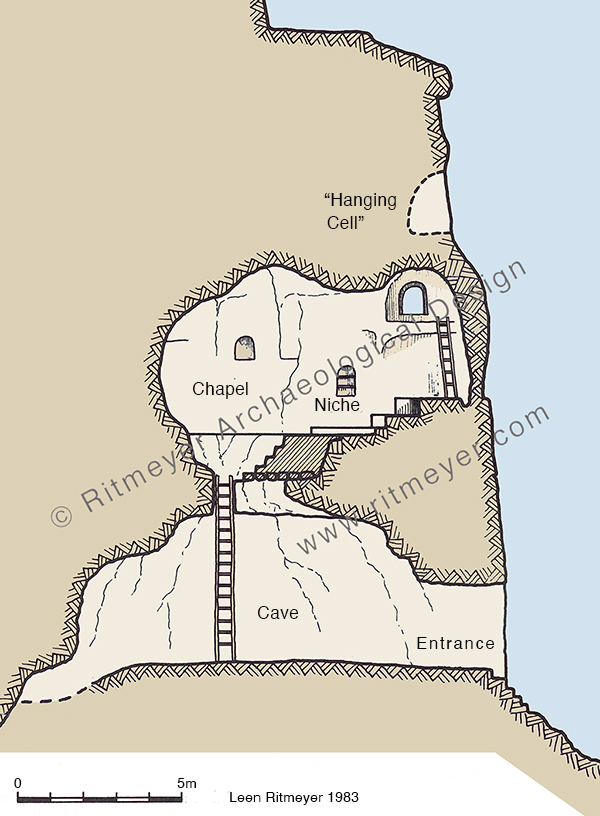

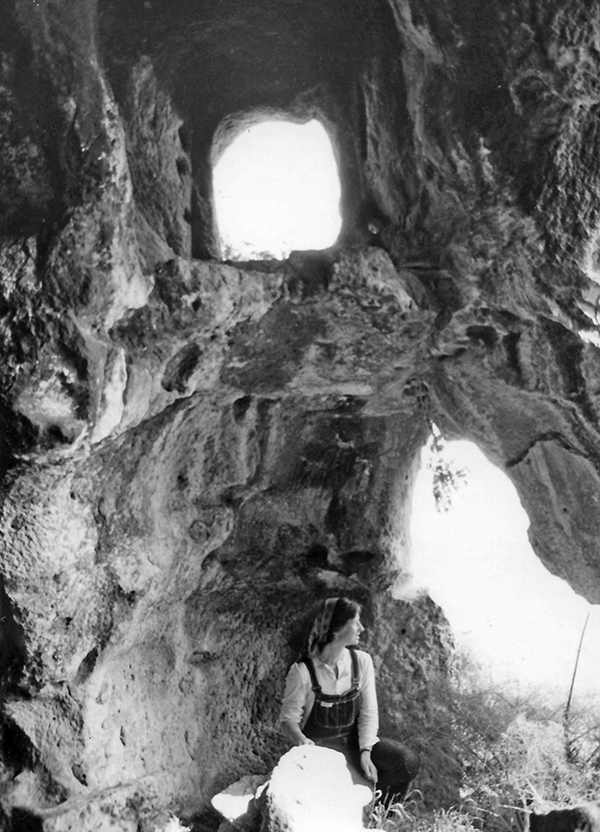

There are two types of monasteries, the laura (from the Greek word for path) is a community of monks who live in individual cells around the church and, walking over the paths that lead from their individual caves to the monastery, meet communally during the weekend. A coenobium (from the Greek koinos bios, meaning communal life) monastery is an enclosed complex where the monks live, work, pray and eat together. Chariton sought solitude in the last years of his life which he spent in the Hanging Cell of St. Chariton.

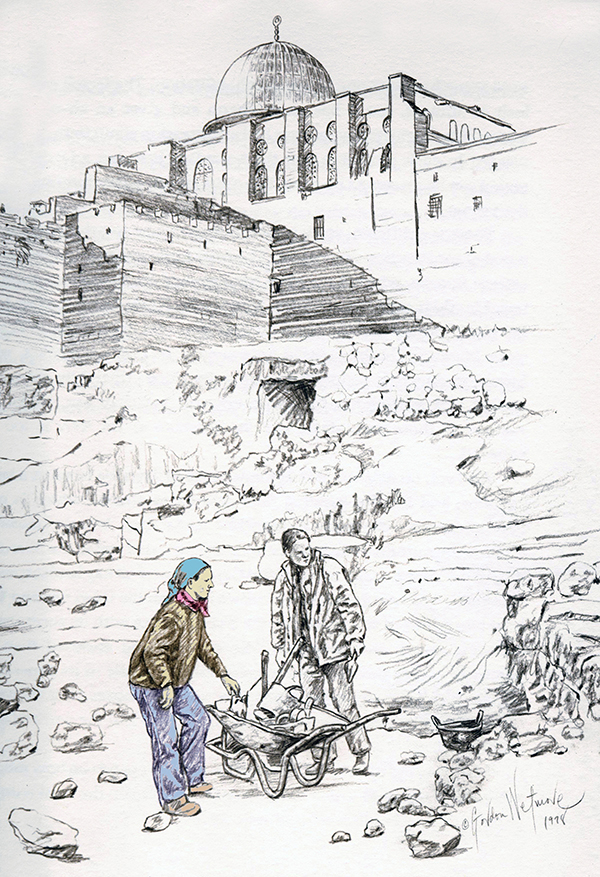

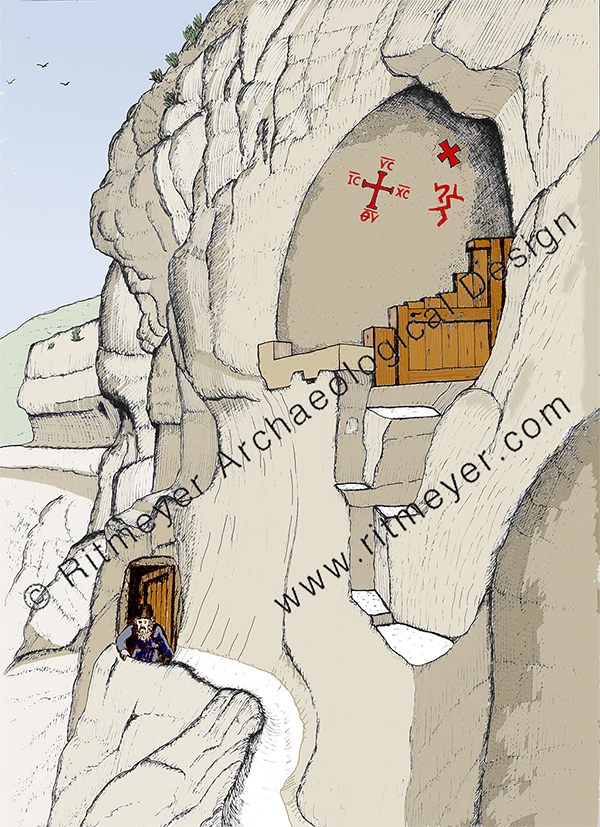

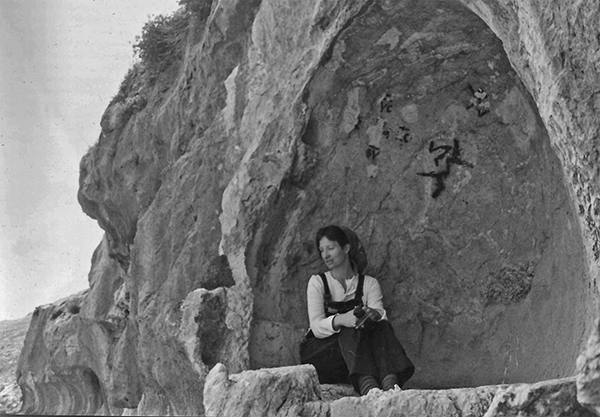

We have fond memories of this Cave Church of St. Chariton in the stunningly beautiful Wadi Khureitun in the heart of the Judean Desert near the settlement of Tekoa.

I had been there already with Yizhar, but I wanted to show Katia this amazing site and take further measurements to help illustrate his book The Judean Desert Monasteries in the Byzantine Period, Yale University press, New York, 1992, for which Katia did a lot of translation work. This is what she wrote about that memorable visit:

“Access to the Cell of St. Chariton was via an iron ladder of 5m in length bolted into the sides of a rocky mountain – quite an adventure! Here you overlook the ravine that at the time we visited was full of wild tulips. There were pine and eucalyptus trees in abundance with natural springs gushing through the cracks in the rock supplying the area with sparkling waters. Standing in the small space with its uneven walls and ceilings covered with soot, we saw how the cave was connected by low passageways to other caves. In these, monks ate, slept and prayed in the “laura” (hermit settlement), established by Chariton. He had originally come on a pilgrimage from Iconium and been abducted by robbers before settling in the Holy Land to establish monasteries.”

“The sight of the birds known as Tristram’s Grackle (with their iridescent black plumage and orange patches on their outer wing, and which are particularly noticeable in flight) diving down from the heights of the cliffs and sweeping upward just before they reach the bottom of the ravine, was incredibly beautiful.”

“The sight of some black desert irises that flower only occasionally in the desert, after a particularly wet winter, near Tekoa, was also very memorable.”

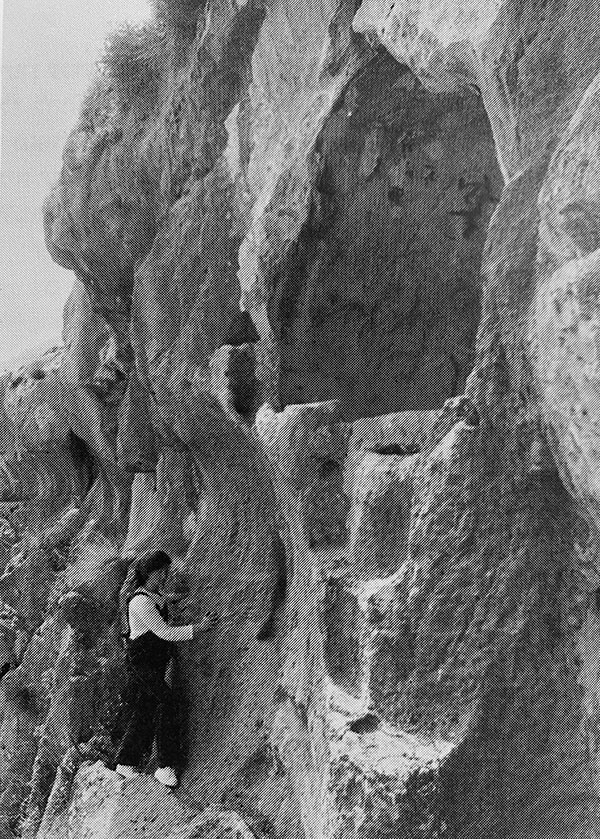

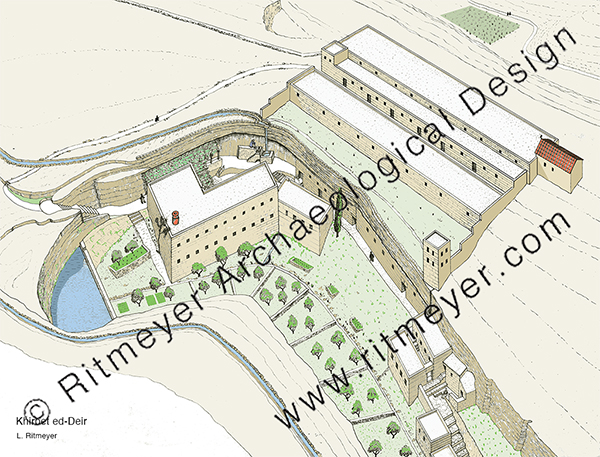

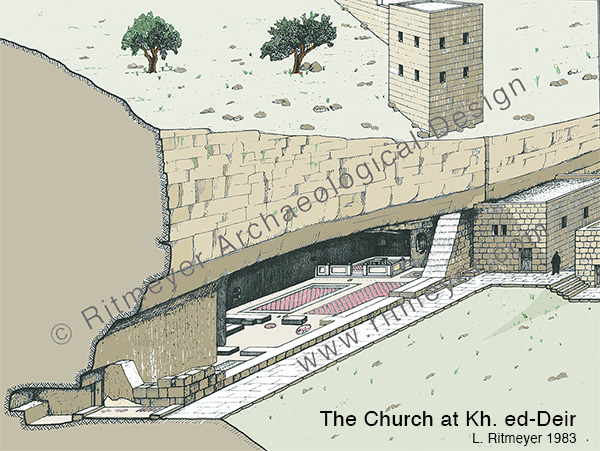

“That same year, we also made a wonderful family trip to Khirbet ed-Deir. Yizhar described it as “one of the most isolated and remote monastic sites of the Judean Desert … the location of the site in the heart of the desert and the excellent preservation of its remains leave a deep impression on the visitor.” It was located in the central part of the dry upper reaches of Nahal Arugot, about ten miles south of Bethlehem.”

“The monastery’s remains are built on a spur that rises above the riverbed’s south bank and along a gorge on the south side of the spur. Natural caves were incorporated into the monastery. It was basically a “cliff-side coenobium” where monks lived together as a commune.”

“While Leen was busy surveying the different parts of the monastery, we had been exploring the gorge and were getting out some drawing materials so that our children could record the visit.”

“Suddenly, a group of Bedouin children appeared out of nowhere, wanting some of the equipment. I gave them some of our novelty pencils and rubbers and chatted with them, telling them what Leen and Yizhar were doing. They were amazed that we were bothering with a small site in the desert, but very pleased with their little gifts.”

“Yizhar was busy bringing out his book on the monasteries in the Judean Desert and we learnt a lot about them through his work. He lent us a book called The Desert a City: an introduction to the Study of Egyptian and Palestinian monasticism under the Christian Empire, by Derwas James Chitty (London, 1966), which, one writer said, was ‘full of brilliant passing insights and wonderful throwaway lines’ about the “City of the Wilderness.”

During our 22 years of work and exploring the Land we visited many memorable sites. Visiting these Byzantine monasteries in the Judean Desert, however, was a major highlight.