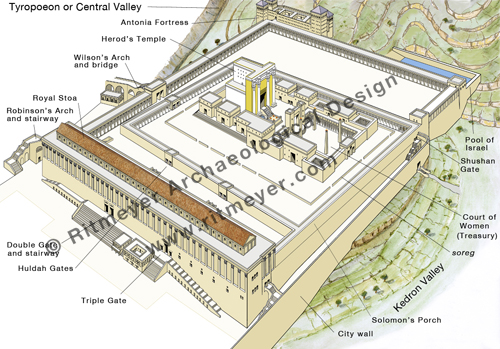

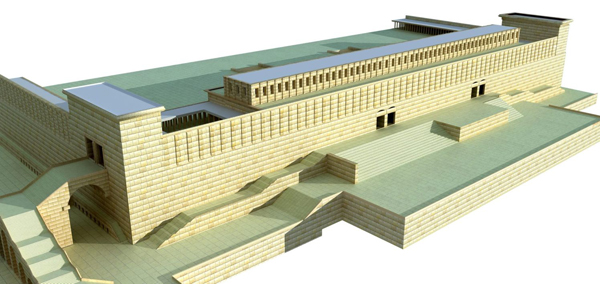

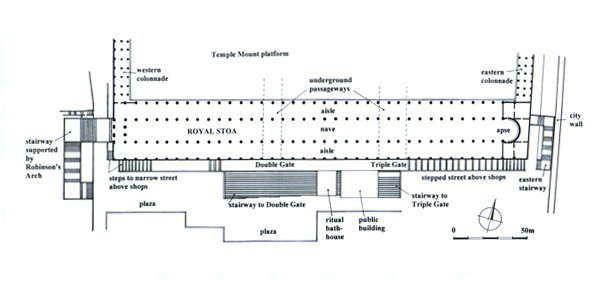

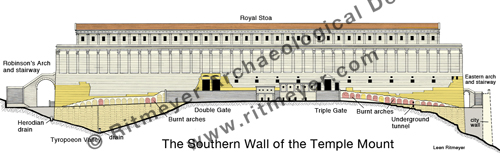

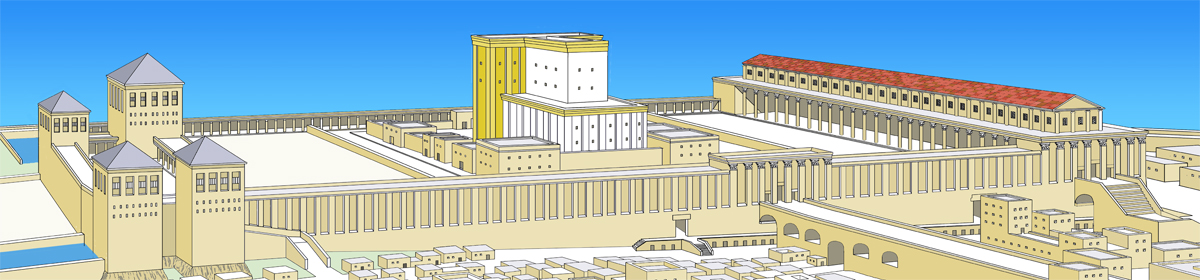

During the Herodian period, a colonnaded hall, known as the Royal Stoa, graced the whole length of the Southern Wall. Constructed in the shape of a basilica with four rows of forty columns each, it formed a central nave in the east end and two side aisles. The central apse was the place of meeting for the Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish Council. The main part of this building was used for the changing of money and purchase of sacrificial animals.

Although the existence and location of this magnificent building was never doubted, questions remain about its plan and decoration. I was pleased therefore to hear of Dr. Orit Peleg-Barkat’s new publication, “Herodian Architectural Decoration and King Herod’s Royal Portico,” that appears in Qedem 57, edited by Eilat Mazar, The Temple Mount Excavations in Jerusalem, 1968–1978 Directed by Benjamin Mazar Final Reports Volume V.

The present volume publishes a rich corpus of 500 architectural decorative fragments from the Second Temple period found in the excavations. The stylistic, technological and historical study of these fragments clarifies issues concerning the architecture, decoration and date of some of the structures built in the southern part of the enclosure, mainly the Royal Portico, one of most elaborate buildings in Judea of this period, and the Double Gate vestibule.

It will be interesting to examine the publication of these decorative elements that were excavated during the time I worked as architect on the Temple Mount Excavations. I am, of course, intimately familiar with most of these elements, but it is good to see them all together. Orit also writes about the plan of the Royal Stoa.

To understand the layout of the Royal Stoa, she had to choose between two conflicting statements by the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius:

Josephus admiringly describes a massive edifice that was a “stadium” long. That Roman unit of measure means that it was from 180 to 200 meters (roughly 600 to 650 feet) long. On the other hand, Josephus also wrote that it stretched the length of the Temple Mount’s southern wall, “from the eastern valley [Kidron] to the western valley [Tyropoeon],” which is about 280 meters.

The historian also wrote that rows of massive columns divided the building into a wide central hall with two side halls: 162 columns in four rows, one built into the wall:

“This cloister had pillars that stood in four rows one over against the other all along, for the fourth row was interwoven into the wall, which [also was built of stone]; and the thickness of each pillar was such, that three men might, with their arms extended, fathom it round, and join their hands again, while its length was twenty-seven feet, with a double spiral at its basis” (Jewish Antiquities 15.413-4)

Based on her study of these elements, Orit concluded that the intercolumniation (that is the space between the columns) of the Royal Stoa was 3.25 m. Secondly, as 162 (columns) cannot be divided by four, she concluded that, despite Josephus’ mention of four rows, this number refers to the three free-standing rows of columns only, i.e. three rows of 54 each. According to her, the Stoa was therefore one stadium long and didn’t stretch from the Western Wall to the Eastern Wall of the Temple Mount. On the other hand, Josephus mentions four rows of forty, while the two remaining ones could have stood in an entrance porch inside Robinson’s Arch (see plan below).

In theory Orit’s suggestion sounds plausible, but the problem is that she relies on text and decorative elements only and doesn’t fully take the architectural remains of the Temple Mount into consideration.

The Royal Stoa was built partly over the 33m (110 feet) deep Tyropoeon Valley and the equally steep western slope of the Kedron Valley.

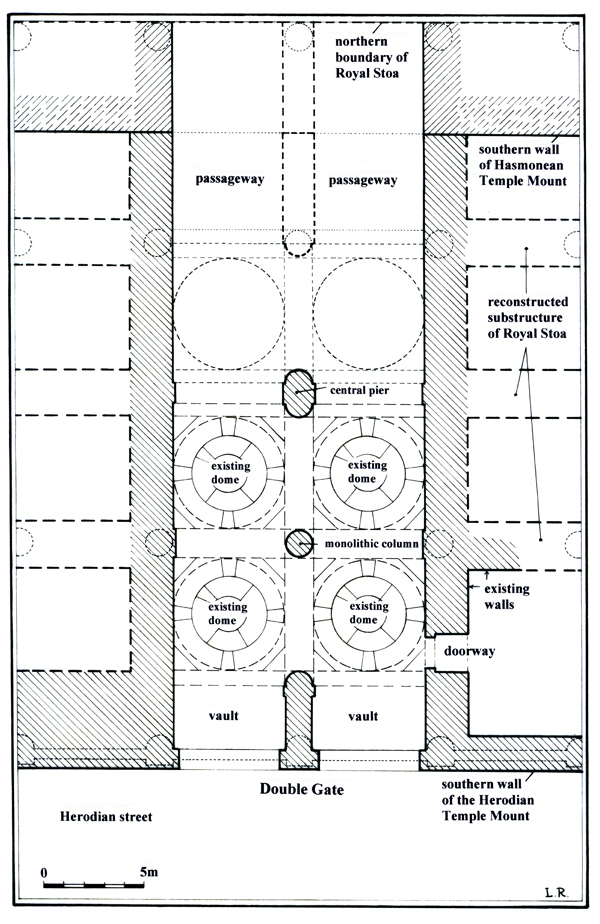

A solid substructure would have been necessary to support the heavy columns of this vast Royal Stoa. As I have shown (The Quest, pp. 60-101), remains of this substructure can be seen in the Double and Triple Gate passageways.

The gate pier, a central pier and one monolithic column with a diameter of 1.45m (4 feet 9 inches) has survived in situ. The Herodian underground passageways are 5.48m (18 feet) wide. The 5.48m reflects therefore the in situ preserved east-west intercolumniation of the Royal Stoa. 40 columns and 39 intercolumniations make approx. 270m, which is the length of the Southern Wall, minus the thickness of the Western and Eastern Walls of the Temple Mount. This makes a perfect fit for Josephus’ description that the “it stretched the length of the Temple Mount’s southern wall”.

At present, the Early Islamic and Crusader buildings of the Islamic Museum, the al-Aqsa Mosque and Solomon’s Stables are aligned along the Southern Wall.

All of these buildings are supported by columns, which, of necessity, must rest on a substructure. It is inconceivable to think that they would have dug down to the bottom of the Tyropoeon Valley to built new foundation walls, while the Herodian substructure was still intact. There are 39 spaces between the columns of these present buildings, which correspond perfectly with the 39 intercolumniations of the Royal Stoa.

The study of ancient buildings needs to be based on four elements:

- The in situ architectural remains

- Comparative architectural styles

- Excavated elements that have belonged to that building

- Historical information

Fortunately, enough information on all of the four requirements is available to reach a satisfactory solution to the plan of the Royal Stoa.

This section of the Final Reports on the Temple Mount Excavations will be a very useful tool for every student of the Temple Mount. We look forward to its insights into the architecture of King Herod, Israel’s Master Builder.

HT: Joe Lauer, Agade

Wow! As usual Mr Ritmeyer, you have brilliantly connected the Temple Mount remains to the historical record to give us an accurate picture of Herod’s original design. Well done, once again!

My take on this, is that the Royal Basilica it self was 185 m long, whereas the substructure of the Royal Basilica was 280 meters. I believe the underground vaulted space (Solomon’s Stables) was a part of the Royal Basilica and I believe it was meant to be the largest water reservoir on the Temple mount, and that rainwater from the Royal Basilica went into the reservoir. I also think Jesus was standing in the Basilicas apse, while he was teaching on the Temple mount, a memory preserved in all the Christian Basilicas around the world.

Sorry, Jesus prophecy was fulfilled and Romans did raze it to the ground.

True, but the supporting walls were below ground.

In my research on the Temple Mount I have encountered a question I have never seen addressed. Animals were sold for sacrifice at the Royal Stoa… but I have never seen anything that speculates on gates used to get them in and out of the city. For that matter they had to be taken from the stoa to the area of the rings for slaughter. (and I suspect other animals were marketed outside the Temple Mount as well). Logically speaking (though logic and archeology aren’t the same thing) It would seem most likely they came in across Wilson’s gate, with some of them going to the right to the stoa others going to the left to the back side of the Temple (but this would mean some sort of gate or ramp was necessary to gain access to the West side of the Priests Court. If anyone could shed some light (even if theoretical) it would be appreciated…)

Terry, already in the Book of Nehemiah 3 and 11 the northern gate of the Temple Mount was called the Sheep Gate. In the Mishnah the gate is called the Tadi Gate (possibly meaning Lamb Gate).The Bethesda Pools were also known as the Probatica, or sheep pools, because of its proximity to the Sheep Gate. Everything points to the northern gate of the Temple Mount where the animals were brought in. They were then kept in pens in the large northern part of the Temple Mount, while the transactions took place in the Royal Stoa, before the animals were sacrificed.

I walked through from the steps leading down outside of Al-Aqsa Mosque to the subterranean area shown in the maps above all the way through to the Southern Wall on the inside when I accompanied the members of the Knesset’s Interior Committee in … 1986, if I correctly recall. (And I checked the newspapers – January 8!).

Thank you so much for illuminating the architecture of the Temple Mount and environs! I was recently studying Koren’s opinion that the Stoa was situated a bit farther north from the Southern Wall, reached by stairs (within the walls) from a lower-set area at the very southern end where the Stoa has (until now) been assumed to have been.

It seems to me that what you show here about the locations of the verifiable columns and supporting piers must be taken into account by any theory or explanation of the space. Could the Koren theory of the Stoa’s location fit in with your findings? Or do your findings dispute the Koren theory?

Thank you!

Hi Sarah,

I have found hard archaeological evidence that shows where the Royal Stoa stood. It also confirms the writings of Josephus. I don’t know why Koren places the Stoa further north. There is no archaeological evidence to support that. Perhaps he thought that the Stoa stood at the southern end of the 500×500 cubit square Temple Mount.

Thank you! I thought that was what you were saying, and appreciate your confirming it. Your archeological evidence seems pretty unassailable. As I recall (I am traveling so don’t have access to my Koren), he bases his “move” of the Stoa on the positions of the stairways on the Temple Mount which lead from the level of the double and triple gates up to the ground surface level of the Temple Mount. He thinks that the southernmost area adjacent the south wall had its floor level down lower (I don’t recall how that would align with the entry doorways from the west and east walls into the area), and then one walked up stairs within the complex to reach the Stoa (rather than the Stoa sitting over the underground stairs).

It is quite impossible to make the southern part of the Herodian Temple Mount lower than it is today. The domes inside the Double Gate are Herodian and I have observed the top of one of these domes a few centimeters below the floor of the El Aqsa mosque during renovations in the 1970’s.

Wow, thank you. Your personal eye-witness experience and dedication to the subject add so much richness and value to us all in understanding this site and the descriptions of what was there.

Is there an estimate as to when the Stoa was completed?

Not that I know of. It took eight years to complete the retaining walls and there was still building acitivity going on in the time of Jesus, but apart from that I could only guess that it would have taken at least 20 years to build the Royal Stoa.