Walking on the Herodian street alongside the Western Wall in the Jerusalem Archaeological Garden and Davidson Centre, one sees an enormous pile of Herodian stones that clearly came from higher up the wall. The excavations in this area by the late Benjamin Mazar and later by Ronnie Reich have proved without a doubt that this destruction occurred in 70AD. The Herodian stones fell on a thin layer of destruction debris that contained many Herodian coins.

As reported first in Haaretz newspaper (in the Premium section which is available to subscribers only, but which was kindly forwarded by email to me by Joe Lauer) and later elsewhere, this view is now challenged by Shimon Gibson, who claims that these stones were destroyed by an earthquake that took place in 363 AD.

He reasons that a Roman bakery that was uncovered by Benjamin Mazar and published by his granddaughter Eilat, would not have been built next to a ruin.

“Who would buy bread in a place with damaged walls above it and fallen stones [adjacent to it]? You don’t build next to a four-story ruin.”

Obviously, people did build next to the four-story high Western Wall, as both the bakery and the Western Wall are still standing there today! We need to remember that the Temple Mount became a symbol of Jewish rebellion against Rome and therefore it was deliberately left in ruins.

“Now we know much more about the late Roman period. If there was a neighborhood like this there, how could it be that they leave debris from the year 70 CE in the middle of it all? It’s like going out of your house and leaving a pile of debris. You clear it.”

Well, that is easier said than done, as these stones were very heavy and difficult to move. Some stones were moved, but only for monumental building activities, such as the Damascus Gate, which was been partly built with Herodian stones in secondary use, and other projects such as the Nea Church and the Umayyad buildings. For smaller projects, such as dwellings, these Herodian stones were cut into smaller stones that were easier to handle.

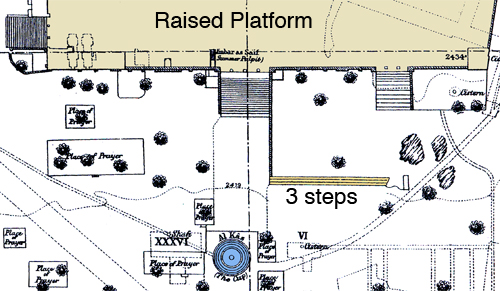

Additionally, as we will see below, there was no heavy stone debris where the bakery was built. The bakery was also not located next to the main Roman street in this area, called the Lower Cardo, but on a street of secondary importance, some distance away from it.

“Gibson believes the builders of these structures used the still-existing Temple Mount walls and imitated their architecture and design as an effort by the Church to show that it – not rabbinic Judaism – was the anointed successor to Temple Judaism.”

A close examination of these structures, however, shows that the Herodian stones in these buildings are in secondary use. They were taken from the Temple Mount wall and moved there.

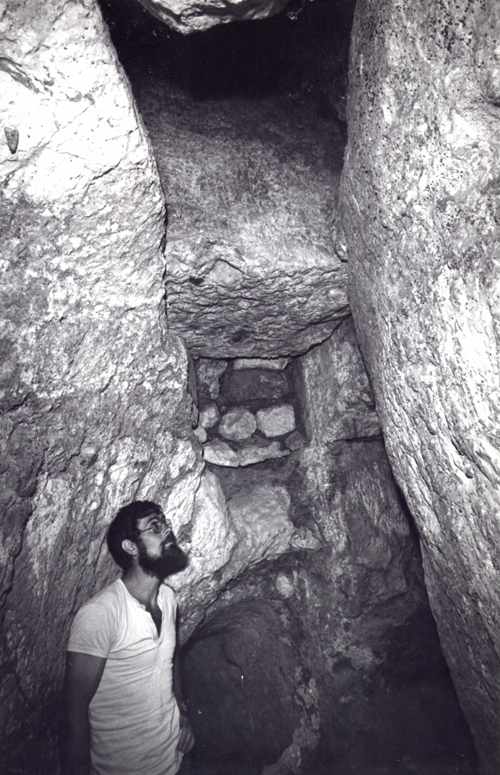

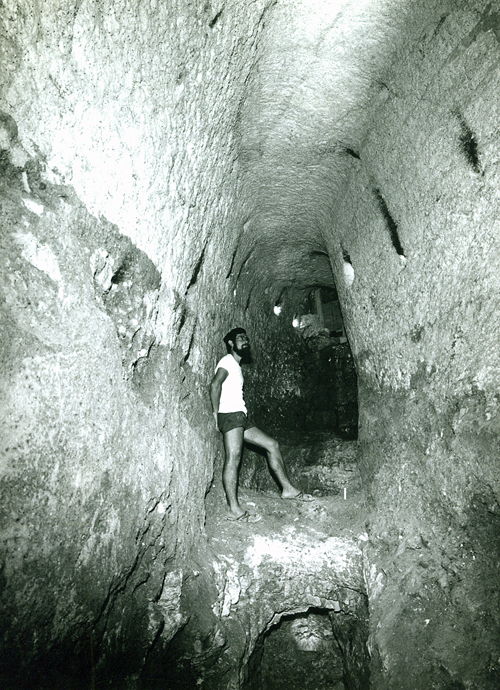

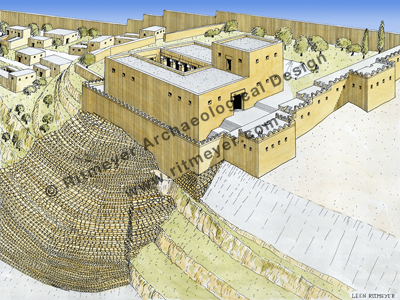

Before making sweeping statements, one should carefully examine the evidence. What kind of “large building stones” do visitors today see lying on the Herodian street? Among the rectangular stones there are many pilaster stones that were toppled down from the upper part of the Western Wall where the western portico stood.

Josephus records that during the struggle for the Temple Mount, these porticoes were burnt and destroyed (War 6.191). The timber beams would have caught fire, the roof was destroyed and the pillars probably fell down on the Temple Mount, leaving only the outer wall, with its pilasters, standing. This upper part of the wall was pushed down by the Romans and fell on the street below, which was covered with a layer of burnt debris containing coins of the Jewish Revolt. Gibson‘s argument that these coins may have been deposited below these stones at a later date, goes against all archaeological logic.

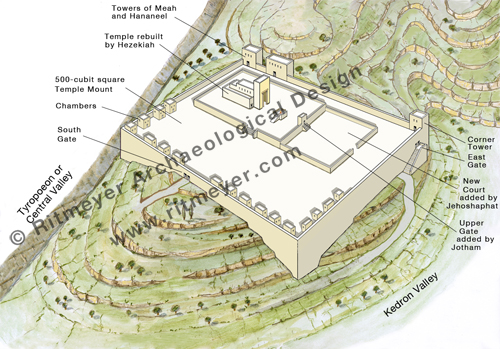

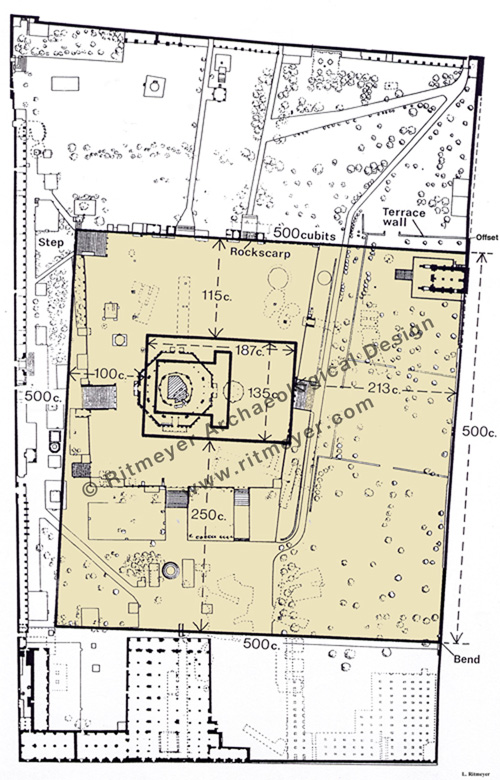

The destroyed stones on the Herodian street were found in front of the pier of Robinson’s Arch as far as the northern edge of the excavations below the Mughrabi Gate ramp which leads up to the Temple Mount, but not south of this point.

No such quantity of stones was found near the southwest corner where the Roman bakery was found.

So, the bakery was not built in the middle of a pile of Herodian stones, as Gibson tries to infer that people believe. Of course, some rubble must have been cleared, but no gigantic mound of stones. That is clear also when one looks up. The Herodian southwest corner, as all other corners of the Herodian Temple Mount, has been preserved to a great height. Only the Trumpeting Stone and a few others were found here lying on the street.

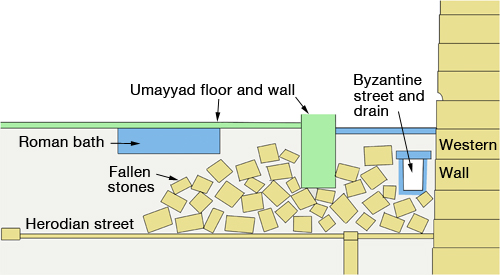

Earthquakes can cause a lot of damage, as happened in 1927 when the al-Aqsa Mosque was almost entirely destroyed. But there is no evidence that an earthquake at any time ever dislodged stones from these massive 5m (15 feet) thick Herodian retaining walls. If the earthquake of 363 AD did destroy the Western Wall, where is the evidence? The heap of fallen Herodian stones is only three meters (10 feet) high. No stones were ever added on top of this, as this Roman destruction was covered by a late Roman bath house and Byzantine street level and drain. The Roman floor level was later covered over by the floor of an Umayyad palace. If the Western Wall was destroyed in 363 AD, then a large pile of stones would have been found on top of the Roman bath house and Byzantine street level which would have been completely destroyed, but no sign of this was found.

It is no wonder that “Gibson’s theory has been vehemently rejected by many.” Happily he said: “If I am wrong, then I am wrong. Life will go on.” I wish him all the best for the new year but think it unlikely that his proposal will cause an earthquake in how we understand this, one of the most significant and moving discoveries of the Temple Mount Excavations.

HT: Joe Lauer