A downloadable pdf of an article by this name written by Israel Finkelstein, Ido Koch and Oded Lipschits is available at http://www.arts.ualberta.ca/JHS/Articles/article_159.pdf

Published in The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures, Volume 11, Article 12, it attempts to provide an answer to the problem that intensive archaeological research on the City of David ridge, conventionally regarded as the original mound of Jerusalem, has proven that:

“between the Middle Bronze Age and Roman times, this site was fully occupied only in two relatively short periods: in the Iron Age IIB-C (between ca. the mid-eighth century and 586 B.C.E.) and in the late Hellenistic period (starting in the second half of the second century B.C.E.). Occupation in other periods was partial and sparse—and concentrated mainly in the central sector of the ridge, near and above the Gihon spring. This presented scholars with a problem regarding periods for which there is either textual documentation or circumstantial evidence for significant occupation in Jerusalem; we refer mainly to the Late Bronze Age, the Iron IIA and the Persian and early Hellenistic periods.”

The solution they put forward is as follows:

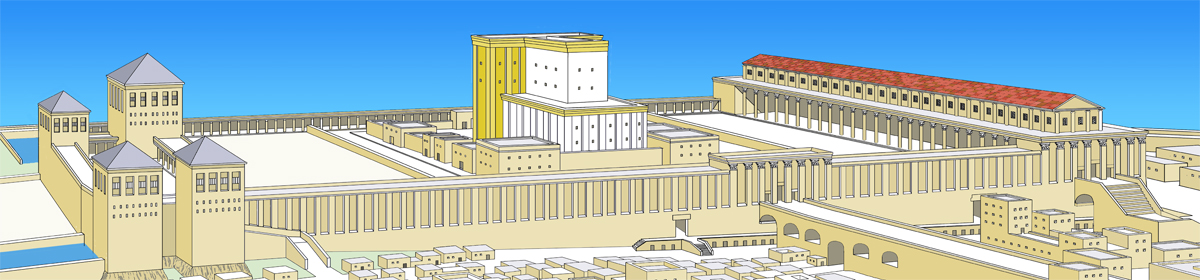

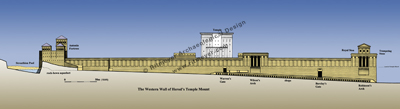

“… we raise the possibility that similar to other hilly sites, the mound of Jerusalem was located on the summit of the ridge, in the center of the area that was boxed-in under the Herodian platform in the late first century B.C.E. Accordingly, in most periods until the second century B.C.E. the City of David ridge was outside the city. Remains representing the Late Bronze, Iron I, Iron IIA, and the Persian and early Hellenistic periods were found mainly in the central part of this ridge. They include scatters of sherds but seldom the remains of buildings, and hence seem to represent no more than (usually ephemeral) activity near the spring. In two periods—in the second half of the eighth century and in the second half of the second century B.C.E.—the settlement rapidly (and simultaneously) expanded from the mound on the Temple Mount to both the southeastern ridge (the City of David) and the southwestern hill (today’s Jewish and Armenian quarters).”

They acknowledge that their theory cannot be proven without archaeological excavations taking place on the mount, something we all know to be impossible and quote N. Naaman, who wrote that: “the area of Jerusalem’s public buildings is under the Temple Mount and cannot be examined, the most important area for investigation, and the one to which the biblical histories of David and Solomon mainly refer, remains terra incognita”, (1996. The Contribution of the Amarna Letters to the Debate on Jerusalem’s Political Position in the Tenth Century B.C.E. BASOR 304: 18-19).

Whilst we cannot deny this, I feel that it is overstates the case. I believe that there are enough clues on the surface and in the walls and underground structures of the Temple Mount to deduce much of the history of Jerusalem. And, with the publication of The Quest – Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the mount is certainly less “incognita”!

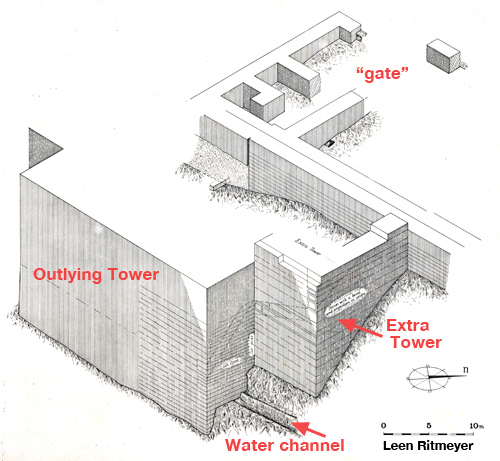

It is true that the area between the Square Temple Mount and the Herodian Southern Wall is quite large and it is possible that some houses were built there in the “missing” periods. The problem, however, is that in 186 B.C. Antiochus IV Epiphanus built the Akra in this location. Some 25 years later, in 141 B.C., this fortress was totally destroyed by Simon Maccabee and the mountain leveled. So, even if one could excavate this area, nothing much would be found.

Additionally, as Todd Bolen also pointed out, the access from the proposed “mound” to the water supply would have been unprotected, which is both unsatisfactory and contradicts the Biblical account that the City of David was located near the Gihon Spring.