My friend and colleague Hillel Geva, director of the Israel Exploration Society and editor cum publisher of the Jewish Quarter Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem Conducted by Nahman Avigad, 1969-1982, sent me a copy of Volume VIII of this important series. Hillel is to be congratulated on the preparation and publication of this beautiful volume which sets a high standard of how excavations should be studied and published.

This Volume VIII describes the excavation of the archaeological remains of the Palatial Mansion, which, as suggested by Avigad, may have been the Palace of the High Priest[1]. This mansion may have been built by Annas who was High Priest from 6-15 AD, as he was one of the few people who could have afforded to build such a large and lavishly decorated residence. The family of Annas was very wealthy as they controlled the Temple Market that was set up in the Temple Courts and out of bounds for normal moneychangers. Josephus called one of the sons of Annas “a great hoarder of money”.

This building covers 600 square meters and is one of the largest residences dating from the Second Temple period ever uncovered, not only in Jerusalem, but in the whole of the country. This mansion is located on the eastern edge of the southwestern hill which slopes down to the Tyropoeon Valley. Overlooking the Temple Mount, it would have been considered prime real estate in the 1st century AD, as indeed it is today.

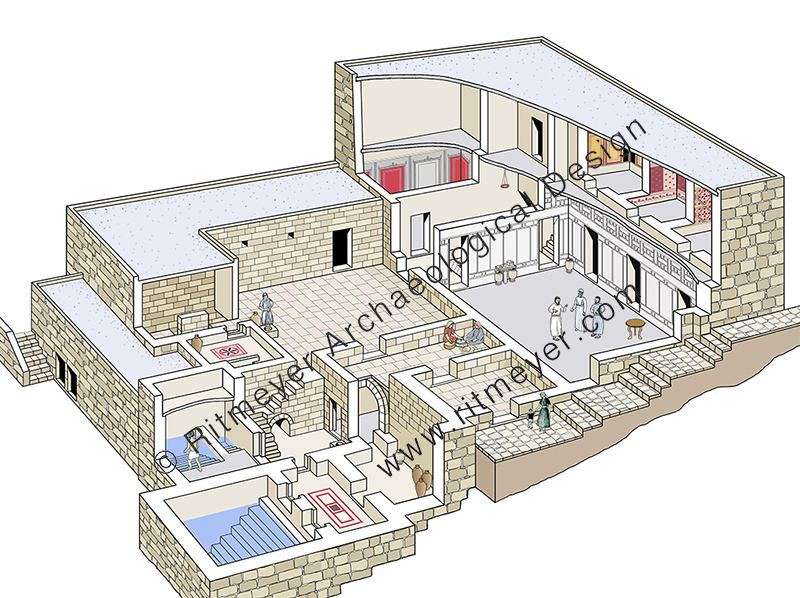

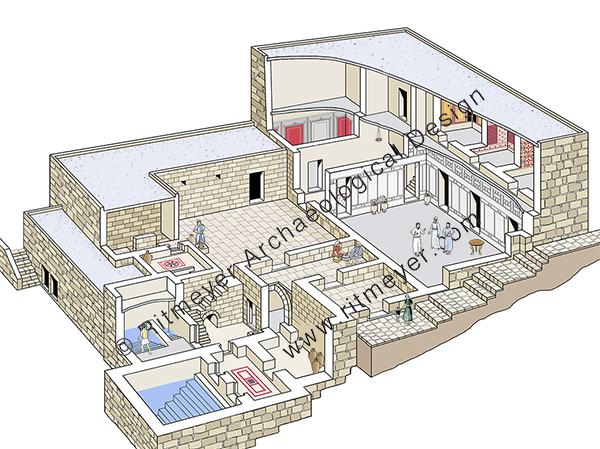

In the first chapter of this magnificent volume, Hillel describes the stratigraphy and architecture of the Palatial Mansion in great detail. The structure is built on two levels, each consisting of two stories and has many rooms built around a central open courtyard. The walls of several of these rooms were decorated with fresco and stucco designs. Seven rooms had mosaic floors, three of which were decorated with colorful carpets.

Eight mikva’ot (ritual baths), catering for the purification requirements of the residents, were found in the mansion indicating that the complex was occupied by priests who served in the Temple.

After making the publication drawings and studying the architectural remains, I made this new reconstruction drawing to give an overall idea of what the mansion may have looked like:

The sumptuousness of its fittings makes it worthy of the term “palace”. It contained eight ritual baths, one evidently built to serve a number of people with one door for entry and one for exit as seen in the lower foreground.

In this volume, every wall and locus is recorded and accompanied by photographs, plans and sections. Of necessity, this takes up the bulk of the book. Different authors have written short chapters on the fresco and stucco decoration, mosaic floors, and ritual baths.

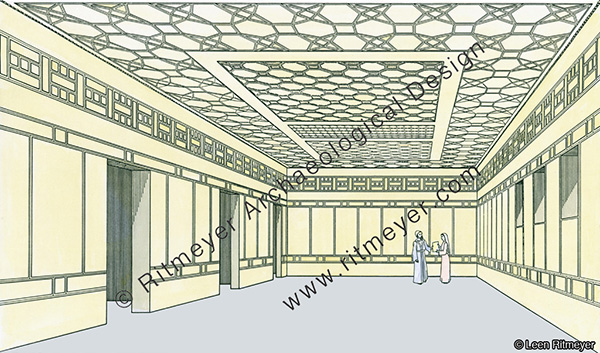

The building was destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD, while it was in the middle of undergoing extensive renovations with fresco wall decorations being covered over with white stucco. This consisted of broad panels in between two bands of imitation masonry, modelled on “headers and stretchers.” However, on the basis of the stucco remains of the northern wall of the Reception Room that extended to the greatest height, it was clear that there was an additional band of decoration just below the ceiling. This different style of imitation stone work could only be reconstructed on the basis of a complete panel which was found in the debris on the floor below this wall – see reconstruction drawing below.

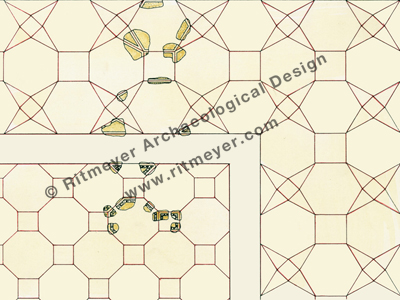

The floor was also found littered with small fragments of decorated stucco with different patterns, which had fallen from the ceiling. Before restoration work on the Palatial Mansion began, Avigad presented me three large trays of a representative sample of ceiling fragments and asked me to try and make some sense of them.

All the pieces showed geometrical patterns in relief. It was clear that the original design must have been divided into two parts, as some fragments had an “egg-and-dart” motif and the remainder were plain. Measuring the angles in the first group – squares, octagons and triangles of 45 degrees could be discerned. The second group consisted of squares, hexagons and triangles of 30 degrees. After trying out various possibilities and taking into consideration the dimensions of the room, the number of fragments found and their representative proportions, I hit upon this ceiling design which was later partially incorporated in the restoration.

I was not part of the original team, as I was then working as architect on the Temple Mount Excavations. However, since 1978, I have spent many years working on the publication plans of all the excavation areas of the Jewish Quarter Excavations. Each of the publication plans, elevations and sections of this magnificent residence including reconstruction drawings, were prepared by me on completion of the excavation.

It should be noted that this volume, like the previous ones, is a scientific publication and of interest to archaeologists, historians and the interested lay person. Other readers may be more interested in a popular book, such as that published by Avigad, who summarised the excavation of this extraordinary mansion in his book Discovering Jerusalem[2]. This Vol VIII is the complete excavation report, published some 30 years after the first spade went into the ground.

When the excavations were finished, a four-story high modern building, the Yeshivat Hakotel (a Jewish school for the study of the Torah and the Talmud) was built over the preserved remains. The mosaic floors were removed and, after conservation, exhibited in the Israel Museum. On completion of the building of the yeshiva, an archaeological museum, named the Herodian Quarter, or Wohl Archaeological Museum, was planned in what had become the basement of the new building. Avigad planned and directed the work for two years, from 1985-87, putting me in charge of its execution. He visited the site twice a week for a couple of hours, leaving me in charge for the rest of the time.

Although in this Volume VIII, only just over two pages are dedicated to this restoration work, it required a lot of thought as to how best to preserve the remains and how to decide where to add stones. Some of the the walls were made higher to help the visitor with spatial orientation. The restoration of the Reception Room demanded special attention as we tried to give an impression of what the beautiful stucco decoration of both the walls and ceiling would originally have looked like. This restoration work was published in book form by Avigad[3]. I treasure my copy of this book which he gave me, inscribed with the dedication “a souvenir from a joint work”.

This volume is a worthy addition to the previous seven volumes of the Jewish Quarter Excavations which cover the excavations of the Broad Wall, the Israelite Tower (later identified as the Middle Gate of Jer. 39:3) and other fortifications, the Byzantine Cardo and the Nea Church, and other buildings of the Second Temple period.

Avigad passed away in 1992 and therefore was unable to publish the final reports of these important excavations directed by him. We are grateful that Hillel Geva, who served as archaeologist since the beginning of the dig, has taken upon himself to publish the results in such magnificent volumes. The next volume will describe the many small finds that were discovered in the Palatial Mansion.

[1] Avigad (1989), 76.

[2] Avigad, N. (1980, [Hebrew]; 1983 [English]). Discovering Jerusalem (Jerusalem, Nashville).

[3] Avigad, N. (1989), The Herodian Quarter in Jerusalem, Wohl Archaeological Museum (Jerusalem).