After Jerusalem, Capernaum is the site most visited by Christian pilgrims and tourists. Their main interest is to see the place where Jesus made his home after his words were rejected in his hometown of Nazareth (Luke 4:16-30).

The fulfilment of the prophecy of Isaiah 9:2: “The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; those who dwelt in a land of deep darkness, on them has light shone”, required that Jesus would move from Nazareth to Capernaum. In the days of Isaiah that great light was Hezekiah, the son of Ahaz, but this prophecy ultimately referred to the future Messiah. Matthew 4:13-17, confirms Isaiah’s prophecy as the main reason why Jesus made Capernaum his home: “And leaving Nazareth he went and lived in Capernaum by the sea, in the territory of Zebulun and Naphtali, so that what was spoken by the prophet Isaiah might be fulfilled: “The land of Zebulun and the land of Naphtali, the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the Gentiles – the people dwelling in darkness have seen a great light, and for those dwelling in the region and shadow of death, on them a light has dawned.”

Capernaum is located in a basalt region and the darkness mentioned in this Scripture is perhaps reflected by the dark basalt stones of which all the buildings were made.

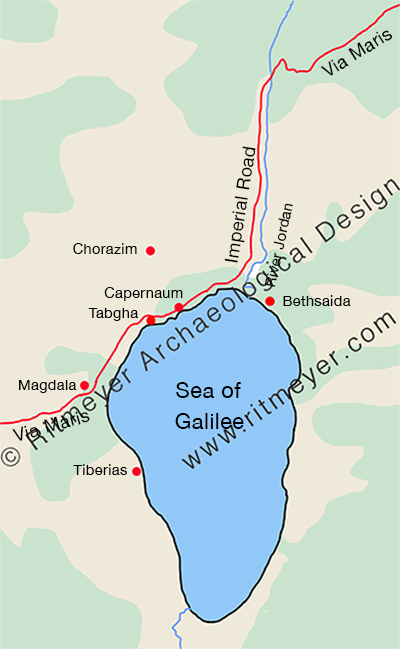

Jesus would, of course, have known beforehand that he couldn’t stay in Nazareth, for it was not located in Galilee of the Gentiles, nor on the Way of the Sea (aka the Via Maris). Bethsaida, for example, was by the sea, but not in the region of Zebulun and Naphtali, and Chorazin (or Chorazim) was not by the sea. Only Capernaum met Isaiah’s criteria. Capernaum wraps around the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee and was located on Via Maris, the major trade route between Syria and Egypt. Jesus’ move from Nazareth to Capernaum was not a retreat into remoteness but a deliberate move into a more diverse region where his message and impact could have a wider and more receptive audience. It was nothing less than a move from the shadows to the spotlight. Capernaum was engaged with the world, via the International Highway and the Imperial Road.

This major highway was used by many traders, who, apart from buying and selling, also exchanged items of news. By living on the Via Maris, Jesus could be assured that what he did and said would be carried far and wide to the larger audience for whom his message was intended. This explains how, according to Matthew 4:24, the fame of Jesus “spread throughout all Syria, and they brought him all the sick, those afflicted with various diseases and pains.” Jesus himself, as far as we know, never went to Syria, but the traders would have told the people they met all about him and the wonderful works he did.

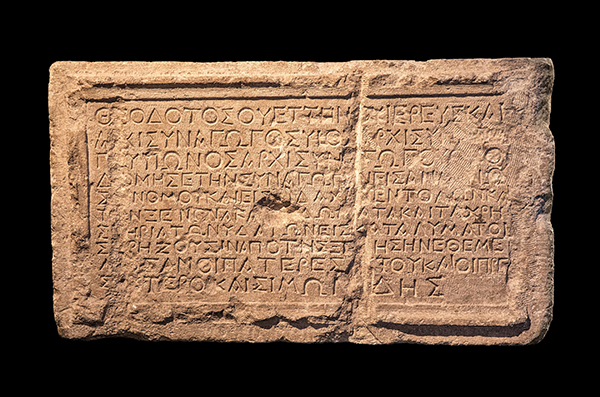

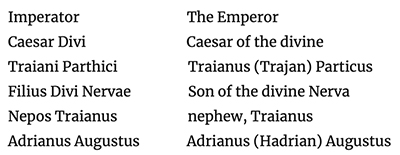

The inscription reads:

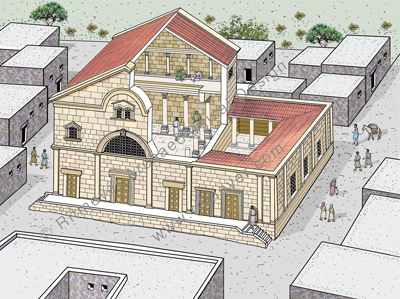

So, what do we know about Capernaum? Excavations by Franciscan archaeologists have revealed that Capernaum was established in the 2nd century BC and abandoned in the 11th century AD. We are going to examine what the major developments of Capernaum were and specially that of Peter’s House.

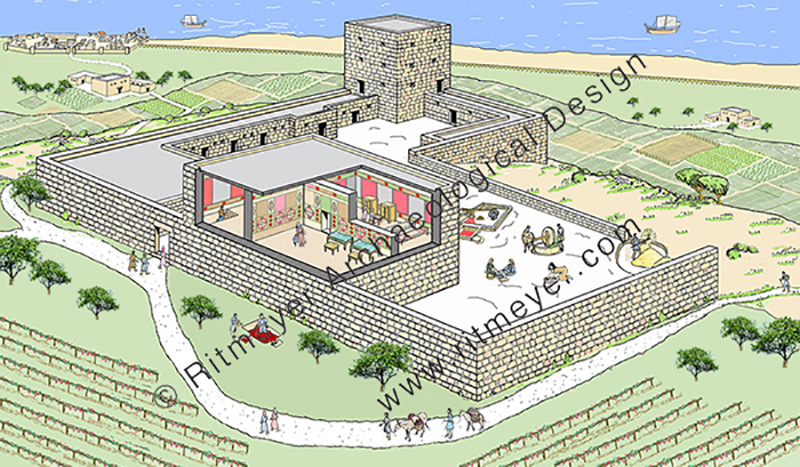

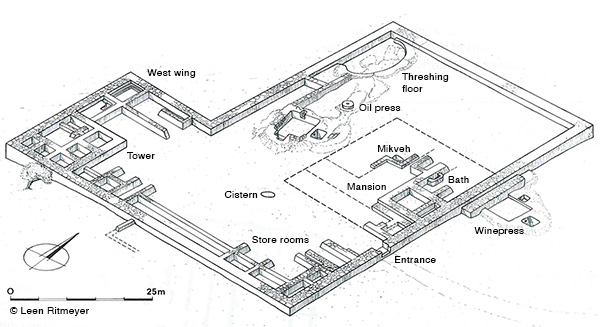

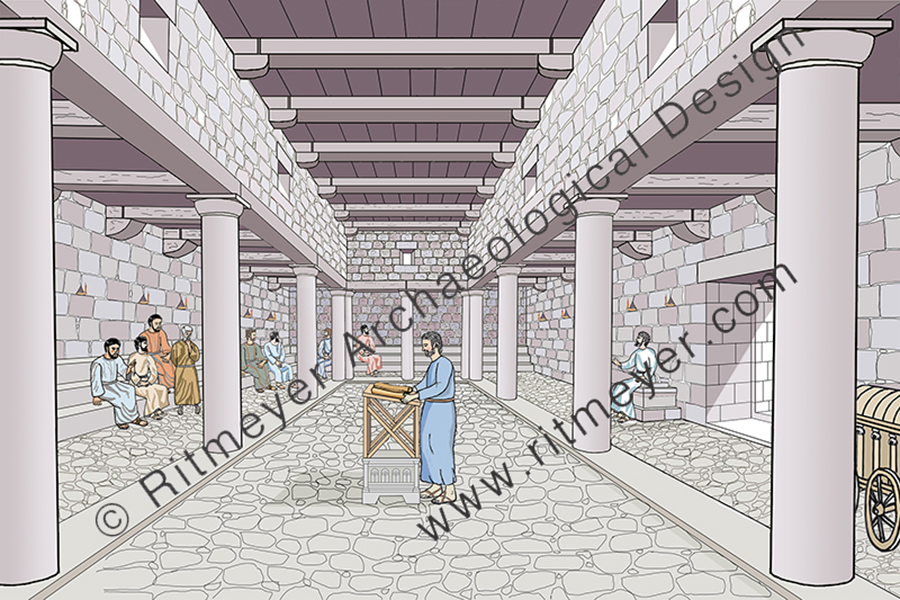

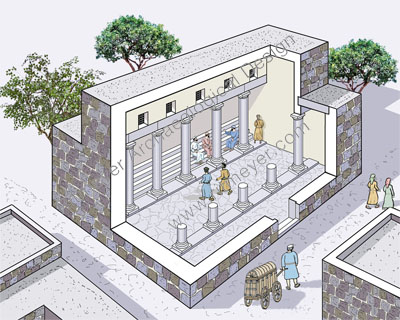

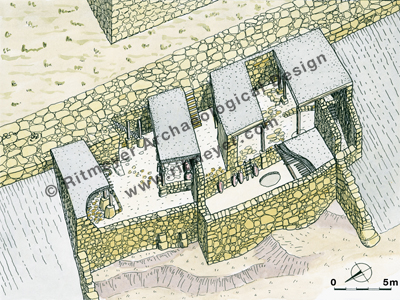

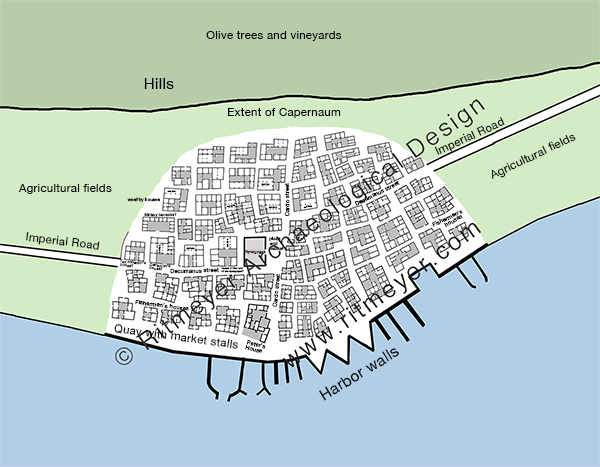

Capernaum was much larger than the excavated area and originally stretched for 300m along the shore and measures about 200m from north to south. The village was probably divided into 4 quarters by the main north-south running Cardo and east-west going Decumanus, with two sections of fishermen’s houses situated on either side of the southern part of the Cardo, close to the sea and harbour, while wealthier houses, such as the ones belonging to the centurion, the ruler of the synagogue and the tax collector, were probably located closer to the hills, away from the harbour and nearer the Decumanus.

The House of Peter where Jesus may have stayed was located west of the Cardo, in between the synagogue (see also here) and the harbour.

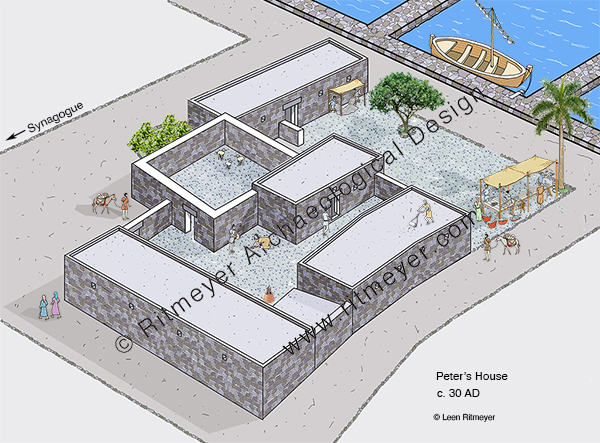

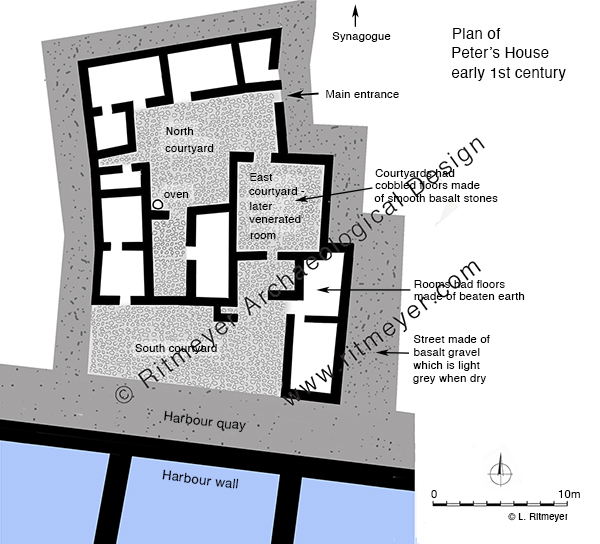

Peter’s House consisted of ten rooms built around three courtyards. Most of the domestic activities took place in the northern courtyard. Animals were kept in the courtyard to the east, and the southern courtyard, which was next to the harbour, was presumably used for fishing activities such as mending nets, selling fish and other activities. Later in the century, the east courtyard was used as a place for religious gatherings.

In this reconstruction drawing we imagine Peter’s boat moored alongside his house. In the courtyard we see two men under an awning mending their nets, and ask ourselves if Jesus perhaps did help Peter sometimes with the mending of the nets? Women are preparing food and baking it in an oven, and there was a stall where fish was sold. On the roof are two stands for the drying of fish.

Capernaum, Kfar Nachum in Hebrew, means the Village of Comfort. Jesus brought comfort to people that suffered from all sorts of diseases, to people that were politically and militarily oppressed by the Romans, to people that wanted to hear the Gospel of the Kingdom of God, but received no spiritual comfort from their Jewish leaders.

Making Capernaum his home, was also a comfort for Jesus. The son of man had not “where to lay his head.” He was often like David in the wilderness, finding rest wherever he could. The story of the healing of Peter’s mother-in-law, who after she was healed “rose and ministered to them” gives the idea that when he was in Capernaum, he probably stayed in one of the rooms in Peter’s house. It shows that Jesus loved being with his friends. We all need friends and so did Jesus.

Over the next few centuries, the House of Peter developed into a church building, which will be the subject of a subsequent post.